The Drumcree conflict or Drumcree standoff is an ongoing dispute over yearly parades in the town of Portadown, Northern Ireland. The Orange Order (a Protestant, unionist organization) insists that it should be allowed to march its traditional route to-and-from Drumcree Church (see map).

———————————

– Disclaimer –

The views and opinions expressed in this blog post are soley intended to educate and provide background information to those interested in the Troubles of Northern Ireland. They in no way reflect my own opinions and I take no responsibility for any inaccuracies or factual errors.

———————————

Drumcree Riots & Background

However, most of this route is through the mainly Catholic/Irish nationalist part of town. The residents, who see the march as sectarian, triumphalist[1] and supremacist, have sought to ban it from their area. The Orangemen see this as an attack on their traditions; they had marched the route since 1807, when the area was mostly farmland.

The “Drumcree parade” is held on the Sunday before the Twelfth of July.

There has been intermittent violence over the march since the 1800s. The onset of the Troubles led to the dispute intensifying in the 1970s and 1980s. At this time, the most contentious part of the route was the outward leg along Obins Street. After serious violence two years in a row, the march was banned from Obins Street in 1986. The focus then shifted to the march’s return leg along Garvaghy Road.

Each July from 1995–2000, the dispute drew international attention as it sparked protests and violence throughout Northern Ireland, prompted a massive police/British Army operation, and threatened to derail the peace process. The situation in Portadown was likened to a “war zone” and a “siege”.

During this time, the dispute led to the killing of at least six Catholic civilians. In 1995 and 1996, residents succeeded in stopping the march. This led to a standoff at Drumcree between the security forces and thousands of Orangemen/loyalists.

Following a wave of loyalist violence, the march was allowed through. In 1997, security forces locked-down the Catholic area and forced the march through, citing loyalist threats to kill Catholics. This sparked widespread protests and violence by nationalists. From 1998 onward the march was banned from Garvaghy Road and the Catholic area was sealed-off with large steel, concrete and barbed-wire barricades.

Each year there was a major standoff at Drumcree and widespread loyalist violence. Since 2001 things have been relatively calm, but moves to get the two sides into face-to-face talks have failed

Some members of Portadown District Loyal Orange Lodge marching in Armagh during the 12 July parades, 2009

Background

An “Orange Arch” in Annalong.

Portadown has long been mainly Protestant and unionist/loyalist. At the height of the conflict in the 1990s, about 70% of the population were from a Protestant background and 30% from a Catholic background. The town’s Catholics and Irish nationalists, as in the rest of Northern Ireland, had long suffered discrimination, especially in employment.

Throughout the 20th century, the police—Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC)—was also almost wholly Protestant. Each summer the town centre is bedecked with loyalist flags and symbols.

A loyalist arch is raised over the Garvaghy Road at the Corcrain River, just inside the Catholic district. This is to coincide with the “marching season”, when numerous Protestant/loyalist marches are held in the town.

Each July there are five Protestant/loyalist parades that enter the mainly Catholic/Irish nationalist district:

- The “Drumcree Sunday” parade from the town centre, to Drumcree Church, and back again. This is the biggest of the parades. Its traditional route was Obins Street→Corcrain Road→Dungannon Road→Drumcree Road→Garvaghy Road, but it is now banned from Obins Street and Garvaghy Road.

- 12 July parade. This involves a morning march from Corcrain Orange Hall to the town centre. The marchers then travel to a bigger parade elsewhere, return to the town centre in the evening, and march back to Corcrain Orange Hall. Its traditional route was along Obins Street, but it is now along Corcrain Road.

- 13 July parade. This follows the same format as the 12th parade.

There is also a junior Orange parade each May along the lower Garvaghy Road at Victoria Terrace.

Before partition

The Orange Order was founded in 1795 in the village of Loughgall, a few miles from Drumcree, after the Battle of the Diamond. Its first ever marches were held on 12 July 1796 in Portadown, Lurgan and Waringstown.

The area is thus seen as the birthplace of Orangeism.

War Walks – The Boyne

In July 1795, the year the Order formed, a Reverend Devine had held a Battle of the Boyne commemoration sermon at Drumcree Church. In his History of Ireland Vol I (published in 1809), historian Francis Plowden described what followed this sermon:

[Reverend Devine] so worked up the minds of his audience, that upon retiring from service […] they gave full scope to the anti-papistical zeal, with which he had inspired them; falling upon every Catholic they met, beating and bruising them without provocation or distinction, breaking the doors and windows of their houses, and actually murdering two unoffending Catholics in a bog.

The first official Orange parade to and from Drumcree Church was in July 1807. Originally and traditionally it was to celebrate the Battle of the Boyne, but the Order now claims that it commemorates the Battle of the Somme during World War I.

See Battle of Somme

Each July, the Orangemen have marched from the town centre to Drumcree via Obins Street/Dungannon Road and returned along Garvaghy Road. In the early 19th century, this area was mostly farmland. In 1835, Armagh magistrate William Hancock (a Protestant) wrote that “For some time past the peaceable inhabitants of the parish of Drumcree have been insulted and outraged by large bodies of Orangemen parading the highways, playing party tunes, firing shots and using the most opprobrious epithets they could invent”. He added that the Orangemen go “a considerable distance out of their way” to pass a Catholic chapel on their march to Drumcree.

There was violence during the Drumcree parades in 1873, 1883, 1885, 1886, 1892, 1903, 1905, 1909 and 1917.

After partition

After the partition of Ireland in 1921, the Northern Ireland Government‘s policy tended to favour Protestant and unionist parades. From 1922 to 1950, almost 100 parades and meetings were banned under the Special Powers Act – nearly all were Irish nationalist or republican. Although violence died down during this period, there were clashes at the 1931 and 1950 Drumcree parades.

The Public Order Act 1951 exempted ‘traditional’ parades from having to ask police permission, but ‘non-traditional’ parades could be banned or re-routed without appeal. Again, the legislation tended to benefit Protestant parades.

In the 1960s, housing estates were built along Garvaghy Road. In 1969, Northern Ireland was plunged into a conflict known as the Troubles. Portadown underwent major population shifts; these new estates became almost wholly Catholic, while the rest of the town’s estates became almost wholly Protestant.

Many Orangemen joined the Northern Ireland security forces: the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) and the British Army‘s Ulster Defence Regiment (UDR).

1970s and 1980s: Obins Street

1972

In March 1972, thousands of loyalists attended an Ulster Vanguard rally in the town, which was addressed by Martin Smyth (‘Grand Master’ of the Orange Order) and the mayor of Portadown. After the rally, loyalists attacked the Catholic neighbourhood around Obins Street, known as “The Tunnel”.[ Following this, Catholic residents formed a protest group named the ‘Portadown Resistance Council’, which called for the upcoming marches to be re-routed away from Obins Street (see map).

The Ulster Defence Association (UDA), a then-legal loyalist vigilante and paramilitary group, warned of consequences if anything was done to stop the march.

The day before the march, Catholics sealed off Obins Street with makeshift barricades. On the morning of the march, Sunday 9 July, British troops and riot police moved in to secure the area. When they bulldozed the barricades they were stoned by Catholic protesters and responded by firing CS gas and rubber bullets.

Once the area was secured, they allowed the 1,200 Orangemen to march along the road, which was lined by at least fifty masked and uniformed UDA members. The UDA men then made their way to Drumcree and escorted the Orangemen back into town along Garvaghy Road.

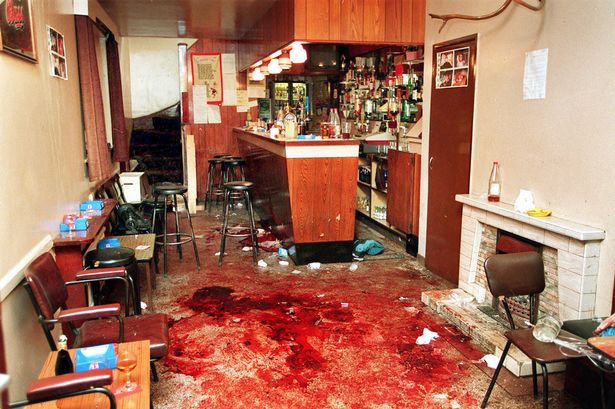

With troops and police out in force, the march passed peacefully. However, on 12 July, three men were shot dead in Portadown. A Protestant, Paul Beattie, was shot in Churchill Park, a housing estate off Garvaghy Road. Hours later, a UDA member (and former police officer) entered McCabe’s Bar and shot the Catholic pub-owner, Jack McCabe, and a Protestant customer, William Cochrane.

That day, under tight security, the Orangemen again marched along Obins Street, this time from Corcrain Orange Hall to the town centre.

On 15 July, Catholic civilian Felix Hughes was kidnapped, beaten, tortured and shot dead by the UDA in a Protestant area of the town. He had been a long-time member of St Patrick’s Accordion Band based on Obins Street.

Later in the month, the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) detonated a bomb on Woodhouse Street, and loyalists bombed a Catholic church. In the Obins Street area there was also a gun battle involving the IRA, the UDA, and the security forces.

The UDA’s involvement in the 1972 dispute made a lasting impression on Portadown’s Catholics and Irish nationalists.

The IRA warned that the UDA would not be allowed to repeat such actions.

DRUMCREE

1985

On Saint Patrick’s Day 1985 the Saint Patrick’s Accordion Band (a local Catholic marching band) was given permission to parade a two-mile ‘circuit’ of the mainly Catholic area. However, a small part of the two-mile route (about 150 yards of Park Road) was lined with Protestant-owned houses.

Arnold Hatch, the town’s Ulster Unionist Party mayor, demanded the march be banned. When the police let it go ahead, Hatch and a small group of loyalists staged a sit-down protest on Park Road. The police forced the band to turn around.

That evening, the band again tried to march the route. Although the protesters had gone, police again stopped the band and there was a confrontation between police and residents. Following this incident, Portadown Catholics boosted their campaign to ban Orange marches from Obins Street. Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP) politician Bríd Rodgers described this incident as “pivotal” in the escalation of the parade dispute.

Shortly before the Drumcree parade of 7 July 1985, hundreds of residents staged a sit-down protest on Obins Street. Present was Eunice Kennedy Shriver, sister of former US president John F. Kennedy.

Among the 2,000 Orangemen were unionist politicians Martin Smyth (the Orange ‘Grand Master’), Harold McCusker and George Seawright. Riot police, armed with batons, forcefully removed the protesters and allowed the march to continue. At least one man was beaten unconscious by police and many were arrested. The whole length of Garvaghy Road was lined with British Army and police armoured vehicles for the march’s return leg.At one point stones were thrown at the marchers and an Orangeman was injured.

Police announced that the 12 and 13 July marches would be re-routed away from Obins Street. On 12 July, eight Orange lodges and hundreds of loyalist bandsmen met at Corcrain Orange Hall and tried to march through Obins Street to the town centre. When they were blocked by police, hundreds of loyalists gathered at both ends of Obins Street and attacked police lines for several hours. These clashes resumed the following evening and loyalists attacked police with ball bearings fired from slingshots. In the two-day clashes, at least 52 police officers and 28 rioters were injured, 37 people were arrested (including two Ulster Defence Regiment soldiers) and about 50 Catholic-owned homes and businesses were attacked.

After this, police erected a barrier at each end of Obins Street.

In July 1985, residents of the Catholic district formed a group called People Against Injustice, later renamed the Drumcree Faith & Justice Group (DFJG). It quickly became the main group representing the residents. The DFJG sought to explain to Orangemen how residents felt about the marches and to improve cross-community relations.

It organized peaceful protests, issued newsletters and held talks with police. It also tried, unsuccessfully, to hold talks with the Orangemen. One of the key figures in this group was a Jesuit priest who, during one of his Sunday sermons in Portadown, suggested that anyone who voted for Sinn Féin should consider themselves excommunicated.

1986

Apprentice Boys of Derry in Manchester – May 2008

The Apprentice Boys of Derry, a Protestant fraternity similar to the Orange Order, had planned to march along Garvaghy Road and through the town centre on the afternoon of 1 April (Easter Monday). On 31 March, police decided to ban the march as it believed loyalist paramilitaries were planning to hijack it. mThat evening, cars with loudspeakers toured Protestant areas and summoned people to gather in the town centre to contest the ban. At 1am, at least 3,000 loyalists gathered in the town centre, forced their way past a small group of police, and began marching along Garvaghy Road.

Ian Paisley at Drumcree 1995

Among them was Ian Paisley, leader of the Democratic Unionist Party and Free Presbyterian Church. Residents claimed that some of the marchers were carrying guns and were known to be members of the police and UDR. Some of the marchers attacked houses along the route and residents claimed the police did little or nothing to stop this.

There followed rioting between residents and the police, and residents set up barricades for fear of further attacks. There was a feeling among locals that police had “mutinied” and refused to enforce the ban. In the afternoon, Apprentice Boys bands tried to enter the town centre for their planned march. When police blocked them, a fierce riot erupted. After negotiations, the bands were allowed to march through the town centre with some restrictions. However, loyalists then attacked police who had sealed off Obins Street. One of the loyalists, Keith White, was shot in the face by a plastic bullet and died in hospital on 14 April.

Police again decided that the Drumcree Sunday parade would be allowed along Obins Street with some restrictions, but that the 12 and 13 July parades would be re-routed. On 6 July 1985, an estimated 4,000 soldiers and police were deployed in the town for the Drumcree parade. Police said the Orange Order had allowed “known troublemakers” to take part in the march, contrary to a prior agreement.

Among them was George Seawright, a unionist politician and Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) member who had proposed burning Catholics in ovens.

See George Seawright

As the march entered the Catholic district, police seized Seawright and others. Orangemen then attacked the police and journalists. A Catholic priest was assaulted by loyalists and at Drumcree a police landrover was overturned. Catholic youths also threw missiles at the police and marchers.

At least 27 officers were injured.

The 12 July march into the town centre was blocked from Obins Street for the second year. Instead, police escorted the march along Garvaghy Road without any bands. Although there was no violence on Garvaghy Road, loyalists later rioted with police in the town centre and tried to smash through the barrier leading to Obins Street.

1987 and 1988

In 1987 the Public Order Act was repealed by the Public Order (Northern Ireland) Order 1987, which removed the special status of ‘traditional’ parades. This meant that, after 1986, Orange marches were effectively banned from Obins Street indefinitely. The July 1987 march was re-routed and 3,000 soldiers and 1,000 police were sent to keep order. Orangemen believed that sacrificing the Obins Street leg meant they would be guaranteed the Garvaghy Road leg.

Although the Garvaghy Road leg had caused trouble before, it was less populated than Obins Street at the time.

In June 1988 the Drumcree Faith & Justice Group (DFJG)—the group representing the Catholic/Irish nationalist residents—planned a march to the town centre to highlight what it saw as “double-standards” in the police’s handling of nationalist and loyalist parades. It asked permission from police, saying there would be only 30 marchers and they would carry no flags or banners. They were denied permission.

1990s and 2000s: Garvaghy Road

A mural supporting the Portadown Orangemen on Shankill Road, Belfast. On the left of the picture is a UDA/UFF flag.

Although a few years passed without serious conflict over the Drumcree parades, both sides remained unhappy with the situation. Orangemen took the new route each year, but continued to apply for marches along Obins Street. Meanwhile, residents of Garvaghy Road and the surrounding Catholic district (see map) remained unhappy about what they viewed as “triumphalist” Orange marches through their area.

They made their opposition known in a number of ways: through the tenants’ associations that represented each housing estate, through the Drumcree Faith & Justice Group (DFJG), and through local politicians. A 1993 survey of people living on Garvaghy Road found that 95% of them were against Orange marches in the area.

Lead-up to July 1995

In 1994, the Provisional IRA and loyalist paramilitary groups called ceasefires.

In May 1995 the Garvaghy Road Residents Coalition (GRRC) was formed, comprising representatives from the DFJG and the tenants’ associations. Its main goal was to divert Orange marches away from Garvaghy Road through peaceful means. It held peaceful protests, petitioned the police and government ministers, and tried to draw media attention to the dispute.

The GRRC held regular public meetings with residents. There were usually about 12 representatives on the committee at any one time . According to one of its members, Joanne Tennyson,

“Although the GRRC could speak to anyone they wanted, at the end of the day no-one in the committee had the right to say we would do anything, not even […] the spokesman. The community had to agree as a whole and that was the purpose of holding public meetings”.

The GRRC’s first secretary and spokesman was Father Eamon Stack, a Jesuit priest and DFJG member who had lived in the area since 1993. Stack emphasized that the GRRC was non-sectarian and was not connected to any political parties. He would remain its spokesman until after July 1997.

By the mid-1990s, the population of Portadown was about 70% Protestant and 30% Catholic. There were three Orange halls in the town and an estimated 40 Protestant/loyalist marches each summer.

1995

On Sunday 9 July 1995, the Orangemen marched to Drumcree Church, held their church service, and then began marching towards the Garvaghy Road. However, hundreds of Catholic residents were holding a sit-down protest on Garvaghy Road to block the march.

Although the march was legal and the protest was not, police stopped the march from continuing. The Orangemen refused to take an alternate route, announcing that they would stay at Drumcree until they were allowed to continue. The Orangemen refused to negotiate with the residents’ group, and the Mediation Network was called upon to intercede. The police and local politicians were also involved in trying to resolve the deadlock.

Meanwhile, about 10,000 Orangemen and supporters had gathered at Drumcree and were engaged in a standoff with about 1,000 police. During this standoff, loyalists continuously threw missiles at the police and tried to break through the police blockade; police responded by firing 24 plastic bullets. In support of the Orangeman, loyalists blocked numerous roads across Northern Ireland, and sealed off the port of Larne.

There was violence in some Protestant areas. On the evening of Monday 10 July, Ian Paisley (Democratic Unionist Party leader) and David Trimble (Ulster Unionist Party leader) held a rally at Drumcree. Afterwards, they gathered a number of Orangemen and tried to push through the police line, but were taken away by officers.

By the morning of Tuesday 11 July, a compromise was reached. The Orangemen would be allowed to march along Garvaghy Road on condition that they did so silently and without accompanying bands. Ronnie Flanagan (Deputy Chief Constable of the police) told the GRRC that residents should peacefully remove themselves from the road because “an angry scene between police and protesters could worsen the Ormeau marching dispute and even destabilise the ceasefires”.

When GRRC member Breandán Mac Cionnaith asked protesters to clear the road, some heckled him and refused. Flanagan was told there would be a better chance of the protesters moving if they knew there would be no march there next year. Flanagan replied that “there was no question of marches going where there was no consent from the community”. The residents were then persuaded to clear the road. This was all confirmed by the Mediation Network.

The Orangemen then marched along the road with Paisley and Trimble at the head of the march. As they reached the end of Garvaghy Road, Paisley and Trimble held their hands in the air in what appeared to be a gesture of triumph. Trimble claims that he only took Paisley’s hand to prevent the DUP leader from taking all the media attention.

Both sides were deeply unhappy with the events of July 1995. Residents were angered that the parade had gone ahead and at what they saw as unionist triumphalism, while Orangemen and their supporters were angered that their parade had been held up by an illegal protest. Some Orangemen formed a group called Spirit of Drumcree (SoD) to defend their “right to march”. At a SoD meeting in Belfast’s Ulster Hall one of the platform speakers said, to applause:

Sectarian means you belong to a particular sect or organisation. I belong to the Orange Institution. Bigot means you look after the people you belong to. That’s what I’m doing. I’m a sectarian bigot and proud of it.

1996

On Saturday 6 July 1996 the Chief Constable, Sir Hugh Annesley, stated that the parade would be banned from Garvaghy Road. Police checkpoints and barricades were set up on all routes into the nationalist area.

On Sunday 7 July the march made its way to Drumcree Church and, after the church service, was again blocked by police barricades. At least 4,000 Orangemen and loyalist supporters began another standoff. That afternoon, Orange ‘Grand Master’ Martin Smyth arrived at Drumcree and announced that there could be no compromise. Over the next three days, buses full of Orangemen and their supporters arrived in Portadown, bringing traffic to a standstill.

By Wednesday night the number of Orangemen and loyalists at Drumcree had risen to 10,000. Again, they pelted the police with missiles and tried to break through the blockade, while police responded with plastic bullets. Loyalists brought an armour-plated bulldozer to Drumcree, threatening to storm the police line.

Throughout Northern Ireland, loyalists blocked hundreds of roads, clashed with the police, and attacked or intimidated Catholics and nationalists. Many towns and villages were blockaded, either completely or for much of the daytime. Several Catholic families were forced to flee their homes in Belfast due to loyalist intimidation. Human Rights Watch said that the police failed to remove these illegal roadblocks and had “abandoned its traditional policing function in some areas”. Loyalists also targeted the homes of police officers, mainly of those on duty at Drumcree. During the disorder, thousands of extra British troops were sent to Northern Ireland, bringing the total number of troops deployed to 18,500.

On the night of 7 July, Catholic taxi-driver Michael McGoldrick was shot dead near Lurgan by the Mid Ulster Brigade of the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF), a loyalist paramilitary group. It is believed the killing was ordered by the brigade’s leader, Billy Wright, from Portadown. Wright was frequently seen at Drumcree in the company of Harold Gracey, head of the Portadown Orange Lodge.

He also held a meeting with David Trimble, leader of the UUP. Members of the brigade smuggled homemade weaponry to Drumcree, apparently unhindered by the Orangemen. Allegedly, the brigade also had plans to drive petrol tankers into the Garvaghy area and blow them up.

On Wednesday 10 July, the police reported that, over the previous four days of loyalist protests, there had been:

- 100 incidents of intimidation

- 758 attacks on the police

- 90 civilians injured

- 50 police injured

- 662 plastic bullets fired by the police and

- 156 arrests made

Shortly before noon on Thursday 11 July, the Chief Constable reversed his decision and allowed the Orangemen to march along Garvaghy Road. The residents’ group had not been consulted on this and rioting erupted as police in armoured vehicles flooded the Garvaghy area and batoned hundreds of protesters off the Garvaghy Road.

About 1,200 Orangemen then marched down the road while residents were hemmed into their estates by riot police.There was outrage among the Catholic/nationalist community, who believed that the police had “surrendered” to loyalist violence and the threat of violence.

An article in the Irish News concluded that “the police did not have the will to impose the rule of law on the Orange Order and loyalists”. The Chief Constable said he believed the situation could no longer be contained. He claimed the crowd at Drumcree was expected to rise to 60,000 or 70,000 that night and would have broken through the defences and attacked the nationalist area. Nationalists argued that the police did nothing to stop the thousands of loyalists from gathering.[42]

Rioting erupted in nationalist areas of Lurgan, Armagh, Belfast and Derry.[41] In Derry, 22 protesters were seriously injured and one, Dermot McShane, died after being run-over by a British Army armoured vehicle.[41] Rioting continued throughout the week, during which time the police fired 6,000 plastic bullets, 5,000 of which were directed at nationalists.[41] The Committee on the Administration of Justice (CAJ), who had sent members to observe the situation, condemned this “completely indiscriminate” use of plastic bullets.[41] Human Rights Watch also accused the police of using “excessive force”.[44] Following the events, leaders of Sinn Féin and the SDLP stated that nationalists had completely lost faith in the police as an impartial police force.[41]

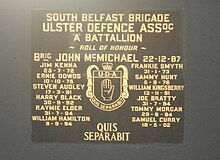

In August 1996, Billy Wright and his Portadown unit of the UVF were ‘stood down’ by the UVF leadership for breaking the ceasefire. The UVF warned Wright to leave Northern Ireland. He ignored the warning, and a large rally was held in Portadown in support of him. Harold Gracey (head of the Portadown Orange Lodge) and William McCrea (a DUP politician) attended the rally and made speeches in support of Wright.[47] Along with most of his Portadown unit, Wright then formed a splinter group called the Loyalist Volunteer Force (LVF).

Following the events of July 1996, many Catholics and nationalists began boycotting businesses run by Orangemen who had been involved in the standoff.[41]

1997[edit]

In May 1997 a local Catholic, Robert Hamill, was kicked to death by a gang of loyalists on Portadown’s main street. He and his friends were attacked while walking home.

Weeks before the July 1997 march, Secretary of State Mo Mowlam privately decided to let the march proceed along Garvaghy Road.[48] However, in the days leading up to the march, she insisted that no decision had been made.[48] Garvaghy Road residents applied to hold a festival on the day of the march. When this was banned by the police, local women set up a peace camp along the Garvaghy Road.[44][48] On Thursday 3 July, the Loyalist Volunteer Force (LVF) threatened to kill Catholic civilians if the march was blocked[48] and the Ulster Unionist Party threatened to withdraw from the Northern Ireland peace process.[49] The following day, sixty families had to be evacuated from their homes on Garvaghy Road after a loyalist bomb threat.[50]

In the days leading up to the march, thousands of British troops were flown to Northern Ireland.[48] Less than twelve hours before the Sunday 6 July march, the authorities still did not say whether it would be blocked. Then, at 3:30 am that morning, 1500 police and soldiers swept into the nationalist area in armoured vehicles and took control of the Garvaghy Road.[48] About 100 residents managed to get to the road and stage a sit-down protest.[51] They were forcefully removed by the police, who were then pelted with stones and petrol bombs as they pushed residents further back from the road.[48] Rosemary Nelson—a prominent human rights lawyer and the GRRC’s legal advisor—was physically and verbally abused by police officers.[51] From this point onward, residents were prevented from leaving their housing estates and accessing the Garvaghy Road.[48] As residents were also unable to reach the Catholic church, the local priests held an open-air mass in front of a line of soldiers and armoured personnel carriers.[48]

The Chief Constable said he had allowed the march to go ahead because of the threat to Catholic civilians by loyalist paramilitaries.[48] About 1,200 Orangemen marched along Garvaghy Road at noon that day.[44] After the march passed, the security forces began withdrawing from the area and severe rioting began. They were attacked by hundreds of nationalists with stones, bricks and petrol bombs. The security forces fired about 40 plastic bullets, and about 18 people were taken to hospital.[48] As news from Portadown emerged, violence erupted in several nationalist areas of Northern Ireland. The Provisional IRA launched numerous gun and bomb attacks on the security forces. Nationalists also attacked the security forces and blocked roads with burning vehicles. There were protests against the police and Orange marches, and a number of Orange halls were burnt. The widespread violence lasted until 10 July, when the Orange Order decided unilaterally to re-route or cancel several marches. By the end of the violence, more than 100 civilians and 60 police officers had been injured, while 117 people had been arrested. There had been 815 attacks on the security forces, 1,506 petrol bombs thrown and 402 hijackings. The police had fired 2,500 plastic bullets.[48]

In 1997, Sinn Féin leader Gerry Adams told an RTÉ journalist of his party’s involvement in the dispute:

Ask any activist in the north, ‘did Drumcree happen by accident?’, and he will tell you, ‘no’. Three years of work on the lower Ormeau Road, Portadown and parts of Fermanagh and Newry, Armagh and in Bellaghy and up in Derry. Three years of work went into creating that situation and fair play to those people who put the work in. They are the type of scene changes that we have to focus on and develop and exploit.[52][53][54]

After July 1997, GRRC member Brendan McKenna (Irish: Breandán Mac Cionnaith) replaced Eamon Stack as the group’s spokesman. Mac Cionnaith had been convicted and imprisoned for his involvement in a 1981 IRA bomb attack on Portadown’s Royal British Legion hall. He was released in 1984.[11][33]

This was the last time that the Orange Order was allowed to march on Garvaghy Road.[55]

1998[edit]

Early in 1998 the Public Processions Act was passed, establishing the Parades Commission. The Commission was now responsible for deciding what route contentious marches should take. On 29 June 1998, the Parades Commission decided to ban the march from Garvaghy Road.[56]

On Friday 3 July about 1,000 soldiers and 1,000 police were deployed in Portadown.[56] The soldiers built large barricades (made of steel, concrete and barbed wire) across all roads leading into the nationalist area. In the fields between Drumcree Church and the nationalist area they dug a trench, fourteen feet wide,[57] which was then lined with rows of barbed wire.[56] Soldiers also occupied the Catholic Drumcree College, St John the Baptist Primary School, and some properties near the barricades.[58]

On Sunday 5 July the Orangemen marched to Drumcree Church and stated that they would remain there until they were allowed to proceed.[56] About 10,000 Orangemen and loyalists arrived at Drumcree from across Northern Ireland.[59] A loyalist group calling itself “Portadown Action Command” issued a statement which read:

As from midnight on Friday 10 July 1998, any driver of any vehicle supplying any goods of any kind to the Gavaghy Road will be summarily executed.[11]

Over the next ten days, there were loyalist protests and violence across Northern Ireland in response to the ban. Loyalists blocked roads and attacked the security forces as well as Catholic homes, businesses, schools and churches.[59] On 7 July, the mainly-Catholic village of Dunloy was “besieged” by over 1,000 Orangemen. The County Antrim Grand Lodge said that its members had “taken up positions” and “held” the village.[59] On 8 July, eight blast bombs were thrown at Catholic homes in the Collingwood area of Lurgan.[59] There were also sustained attacks on the security forces at Drumcree and attempts to break through the blockade.[59] On 9 July, the security forces at Drumcree were attacked with gunfire and blast bombs; they responded with plastic bullets.[59] The police recorded 2,561 “public order incidents” throughout Northern Ireland,[56] including:[56]

- 615 attacks on the security forces, which left 76 police offices injured

- 24 shooting incidents

- 45 blast bombs thrown

- 632 petrol bombs thrown

- 837 plastic bullets fired by the security forces

- 144 houses and 165 other buildings attacked (the vast majority owned by Catholics/nationalists)

- 467 vehicles damaged and 178 vehicles hijacked, and

- 284 people arrested

On Sunday 12 July, Jason (aged 8), Mark (aged 9) and Richard Quinn (aged 10) were burnt to death when their home was petrol bombed by loyalists.[56] The boys’ mother was a Catholic, and their home was in a mainly-Protestant part of Ballymoney. Following the murders, William Bingham (County Grand Chaplain of Armagh and member of the Orange Order negotiating team) said that “walking down the Garvaghy Road would be a hollow victory, because it would be in the shadow of three coffins of little boys who wouldn’t even know what the Orange Order is about”. He said that the Order had lost control of the situation and that “no road is worth a life”.

However he later apologized for implying that the Order was responsible for the deaths. The murders provoked widespread anger and calls for the Order to end its protest at Drumcree. Although the number of protesters at Drumcree dropped considerably, the Portadown lodges voted unanimously to continue their standoff.

On Wednesday 15 July the police began a search operation in the fields at Drumcree. A number of loyalist weapons were found, including a homemade machine gun, spent and live ammunition, explosive devices, and two crossbows with more than a dozen homemade explosive arrows.

1999

In the year after July 1998, the Orange Order and GRRC tried to resolve the dispute through “proximity talks” using go-betweens, as the Orangemen refused to talk directly to the GRRC. Some senior Portadown Orangemen claim that they had been promised a parade on Garvaghy Road later that year if they could control things on the traditional parading dates.

Throughout the year the Orangemen and supporters held scores of protest rallies and marches in Portadown. Following one protest in September 1998, a Catholic RUC officer was killed by a blast bomb thrown by loyalist rioters. A renegade loyalist group, the Orange Volunteers, also began carrying out attacks on Catholics and Irish nationalists.

On 14 March 1999, the Parades Commission said the yearly march would again be banned from Garvaghy Road. The following day the GRRC’s legal advisor, Rosemary Nelson, was assassinated in Lurgan by loyalists.

In April, Portadown loyalists threatened to picket St John’s Catholic Church at the top of Garvaghy Road. On 29 May a ‘junior’ Orange march passed near Garvaghy Road. There were clashes following the march with 13 police officers and four civilians hurt. The police fired 50 plastic bullets during the clashes.

That month, DUP politician and Orangeman Paul Berry said Orangemen would not be stopped from marching the Garvaghy Road:

“If it is a matter of taking the law into our own hands then we are going to have to do it. That is a threat”.

On 24 June, Orangemen began a ten-day ‘Long March’ from Derry to Drumcree in protest at the ban.[63] The 1999 Drumcree march took place on Sunday 4 July. About 1,300 Orangemen marched to Drumcree and were met by several thousand supporters. The security forces had again blocked all roads leading into the nationalist area with large steel, concrete and barbed wire barricades. Rows of barbed wire were also stretched across the fields at Drumcree. There, loyalists threw missiles at police and soldiers, but there was less violence than the year before.

On 5 July, police in Portadown arrested four Belfast loyalists after finding pickaxe handles, wire cutters, petrol and combat clothing in their car. Later that day, six officers were hurt in clashes with loyalists near Garvaghy Road. The barricades were eventually removed on 14 July.

On 31 July, a drunken loyalist wielding an AK-47 and a handgun crossed the interface to Craigwell Avenue, a street of Catholic-owned houses. A resident wrestled him to the ground and disarmed him, but was shot and wounded while doing so. The loyalist was arrested and later convicted for attempted murder. In August, breeze blocks were thrown through the windows of houses on the street.

Also that year, the GRRC published a book detailing the history of Orange parades in the area. The book was called Garvaghy: A Community Under Siege.

In 1999, the Orange Order’s membership for the Portadown district, which had increased from 1995 through 1998, began a “catastrophic slump”.

2000 marching season

April-June

In April 2000, a newspaper reported that Portadown Orangemen had threatened British Prime Minister Tony Blair, saying that if that year’s march was banned from Garvaghy Road it would prove to be his “Bloody Sunday“.

The following month, almost 200 masked loyalists attacked Catholic-owned houses on Craigwell Avenue after assembling at Carlton Street Orange Hall. Allegedly, police landrovers were nearby but did not intervene.

On 27 May, the nationalist area was sealed-off so that a ‘junior’ Orange parade could march along the lower end of Garvaghy Road. The march included men in paramilitary uniform.

On 31 May, a children’s cross-community concert at St John’s Catholic Church was disrupted by Portadown Orangemen beating Lambeg drums, allegedly trying to drown it out. Present at the concert were Secretary of State Peter Mandelson and UUP leader (and Orangeman) David Trimble.

After the concert, teachers, parents, children and guests held a reception at the Protestant Portadown College. A 300-strong loyalist mob hurled missiles and sectarian abuse while preventing families from leaving the College. The security forces were deployed but did not disperse the mob or make arrests.

On 7 June, St John’s Catholic Church was set alight by arsonists.

On 16 June, Catholic workers at Denny’s factory in Portadown walked-out after placards carrying sectarian slogans were erected near the main entrance. The week before, loyalists had thrown missiles at Catholics leaving the factory. The placards were removed shortly after. Later in the month, loyalists sent death threats to workers who were reinforcing the security barrier (or “peace line“) along Corcrain Road. The work stopped, leaving the nationalist area vulnerable to attack.

July

In July, it was revealed that members of neo-Nazi group Combat 18 were travelling from England to join the Orangemen at Drumcree. They were given shelter by LVF members in Portadown and Tandragee. That month, Portadown Orangeman Ivan Hewitt (who sported neo-Nazi tattoos) warned in a TV documentary that it may be time for loyalists to “bring their war to Britain”.

The 2000 Drumcree march took place on Sunday 2 July. It was again banned from Garvaghy Road and the nationalist area was sealed off with barricades. Speaking after the march was stopped, Orange ‘District Master’ Harold Gracey called for protests across Northern Ireland.

A prominent leader of the protesters, Mark Harbinson, a Stoneyford Orangeman who was associated with the paramilitary Orange Volunteers, proclaimed that “the war begins today”. On Monday 3 July a crowd of over fifty loyalists, led by UDA commander Johnny Adair, appeared at Drumcree with a banner bearing “Shankill Road UFF” [Ulster Freedom Fighters]. In the Corcrain area, LVF gunmen fired a volley of shots in the air for Adair and a cheering crowd.

On Tuesday 4 July, security forces used water cannon against loyalist protesters at the Drumcree barricade. This was their first deployment in Northern Ireland for over 30 years.

In an interview on 7 July, Harold Gracey refused to condemn the violence linked to the protests, saying “Gerry Adams doesn’t condemn violence so I’ll not”. On 9 July, the police warned that loyalists had threatened to “kill a Catholic a day” until the Orangemen were allowed to march along Garvaghy Road.

Two days later, a group of 150–200 loyalists ordered all shops in Portadown’s town centre to shut. Along with another group, they then tried to march on Garvaghy Road from both ends, but were held back by police. That night, 21 police officers were hurt during clashes with loyalists.

On 14 July, Portadown Orangemen’s calls for another day of widespread protest went unheeded as the Armagh and Grand Lodges refused to support their calls. Businesses remained open and only a handful of roads were blocked for a short time. The security barriers were removed and soldiers returned to barracks.

2001 onward

Since July 1998, the Orangemen have applied to march the traditional route every Sunday of the year – both the outward leg via Obins Street (which has been banned since 1986) and the return leg via Garvaghy Road.They have also held a small protest at Drumcree Church every Sunday. Their proposals have been rejected by the Parades Commission.

In February 2001, loyalists held protests on the lower Garvaghy Road as part of the run-up to “day 1000” of the standoff. The GRRC said that up to 300 people, some masked and armed with clubs, intimidated people living on Garvaghy Road. Some protesters also attacked a car with four women inside.[

There was further violence in May 2001. On 5 May, 300 Orangemen and supporters tried to march on to Garvaghy Road but were stopped by police. There were some scuffles between Orangemen and police officers. District Master Harold Gracey drew controversy when he said to the police officers: “We all know where you come from…you come from the Protestant community, the vast majority of you come from the Protestant community and it is high time that you supported your own Protestant people”.

On 12 May there were clashes between loyalists and nationalists on Woodhouse Street. On 27 May there were clashes between nationalists and police after a junior Orange march on the lower Garvaghy Road.

Four days before the July 2001 Drumcree march, 200 supporters and members of the UDA rallied at Drumcree. The Portadown Orange Lodge claimed that it was powerless to stop such people from gathering and that they could not be held responsible for their actions. Nevertheless, David Jones (the Lodge’s spokesman) said that he welcomed any support. Bríd Rogers, a local SDLP politician, called this “a further example” of the Orangemen’s “double standards”. She said that the Orangemen would not speak to the GRRC because of Mac Cionnaith’s “terrorist past”, yet they are “quite happy to associate with people who have a terrorist present”.

The march passed off peacefully under a heavy security presence.

Since 2001 Drumcree has been relatively calm, with outside support for the Portadown lodges’ campaign declining and the violence lessening greatly. Mac Cionnaith said that he believes the conflict is essentially over. The Orange Order continues to campaign for the right to march on Garvaghy Road.

Map

Routes of the Protestant parades before they were banned from Obins Street (A) in 1986.

Red line:

Route taken by Orangemen on the Sunday before 12 July; from their Carlton Street Hall (D) under the railway bridge (C) along Obins Street (A) to Drumcree Church (F) and back along Garvaghy Road (B).

Blue line: Route taken on 12 July; from Corcrain Hall (E) along Obins Street (A) and under the railway bridge (C).

Green areas are largely nationalist/Catholic.

Orange areas are largely unionist/Protestant.

———————————

– Disclaimer –

The views and opinions expressed in this blog post are soley intended to educate and provide background information to those interested in the Troubles of Northern Ireland. They in no way reflect my own opinions and I take no responsibility for any inaccuracies or factual errors.

———————————