Should I Stay or Should I Go ?

I’m torn between going or staying .

Throughout my time living and working in London and recent years in and around the North West of England it was always my long term intention that when I reached a ripe old age and my kids had settled into happy secure independent adult lives I would relocate to Belfast and spend the remainder of my time in the company of friends and loved ones and the Shankill community that has always been my spiritual home and where my heart and soul were forged within the heartlands and hallowed streets of loyalist Belfast .

You can take the boy out of the Shankill but you can’t take the Shankill out of the boy , Oh so true .

But as usual my path through life has seldom been straight forward and the Norms in their infinite wisdom and cruel nature weaved me a crooked path fluctuating between epic highs and soul destroying lows.

To be honest these past five years have been the most trying and stressful I’ve faced in decades of relative happiness and personal satisfaction and to say they have taken a toll on my mental and emotional wellbeing would be something of an understatement.

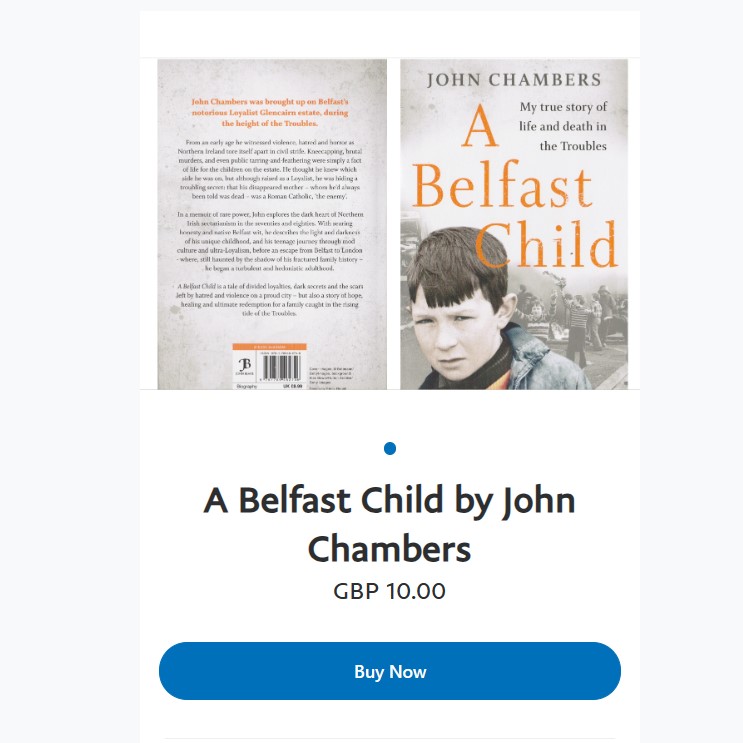

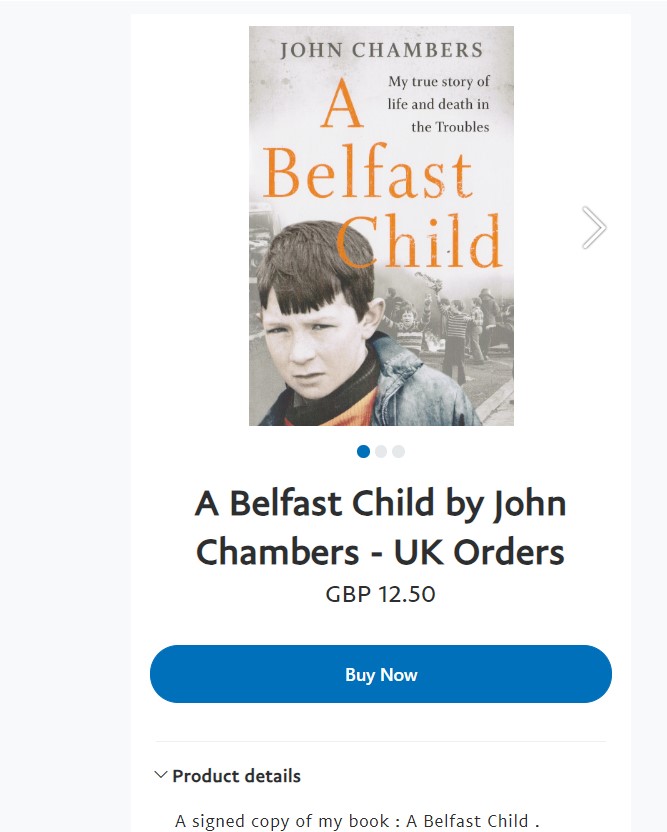

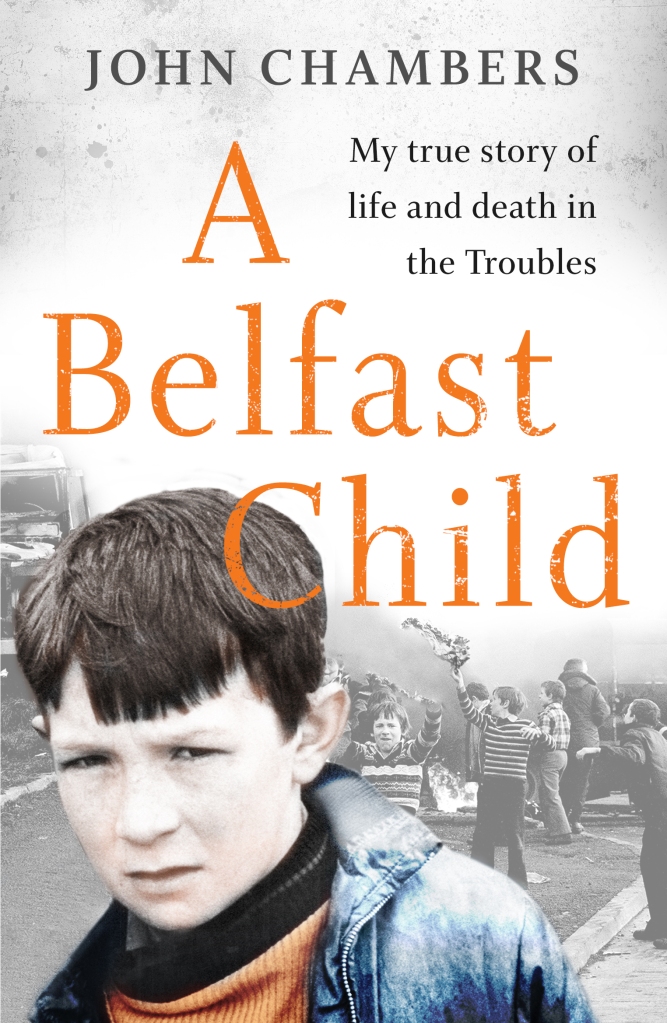

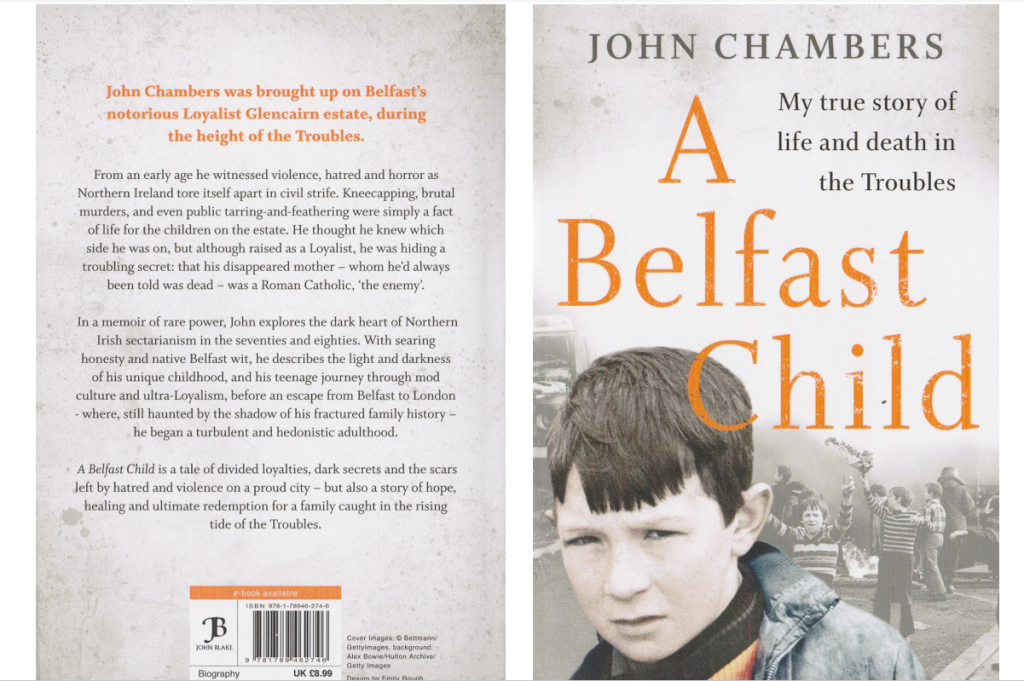

Looking back it all started to fall apart when I lost my much missed and loved mum to cancer, a heartbreaking period that I am still trying to come to terms with. If you are familiar with my history, you’ll know I spent many years not knowing if mum was alive or dead and the turmoil this caused throughout my early and teenage years is laid bare in my best-selling book A Belfast Child .

Come on – I had to get a plug in somewhere 😜

In fact back in the early 2000’s I was seriously considering leaving London altogether (I’d had enough of the rat race and a coke habit that was threatening to get out of hand ) and the possibility of moving back to Belfast and sorting myself out was one of two tempting options opened to me and my growing family. Mum was the second and she made it crystal clear she would love for me to live closer to her and help me get back on my feet . So I delayed my return home and we relocated to a little town on the outskirts of Preston, where we have lived since.

It was great to be so close to mum and we were able to spend quality time together getting to know each other and mending the damage of our tragic family history. The gravitational weight of my traumatic childhood has been a constant presence throughout my life and parts of my soul will always be held hostage to the past.

Nevertheless, this was one of the happiest and most productive periods of my life and at times it seemed I had an almost perfect life and wanted for nothing.

But as the years ticked by the pull of Belfast was becoming stronger and I missed and longed to be in the company of those I love and cherished above all others. Mostly I missed my three siblings and best mate “ Billy “ , we are supernaturally close and I grew to resent the years I had spent away from them.

And a little voice inside my head constantly reminded me that we were only given a brief spell on this mortal coil and time was running out.

Time keeps on slipping into the future

My biggest fear , a fear shared by all of us was that one of us might die prematurely and the landscape and future of our close family unit would be reshaped and destroyed forevermore.

After mums’ death the only thing keeping me in England was the fact my two children had been born and raised here and all their memories and historical roots were firmly planted in English soil . So once again I kicked the idea of the move home into the long grass and settled into the humdrum existence of daily life.

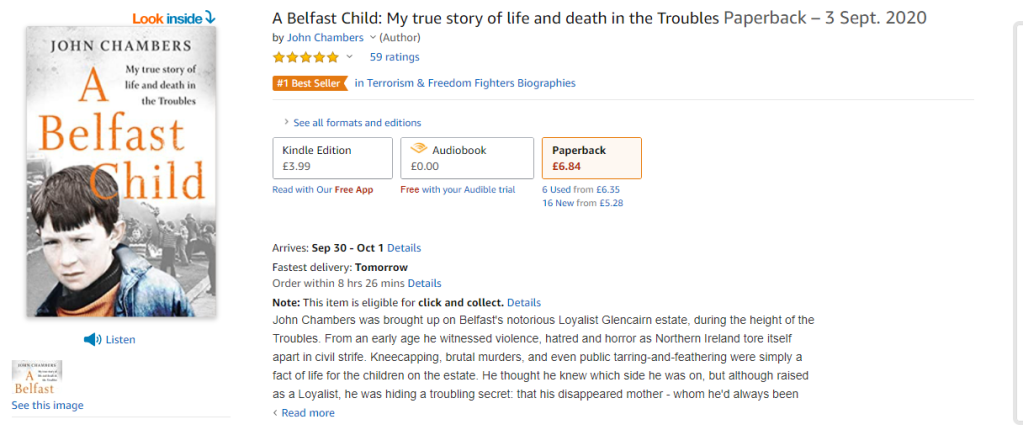

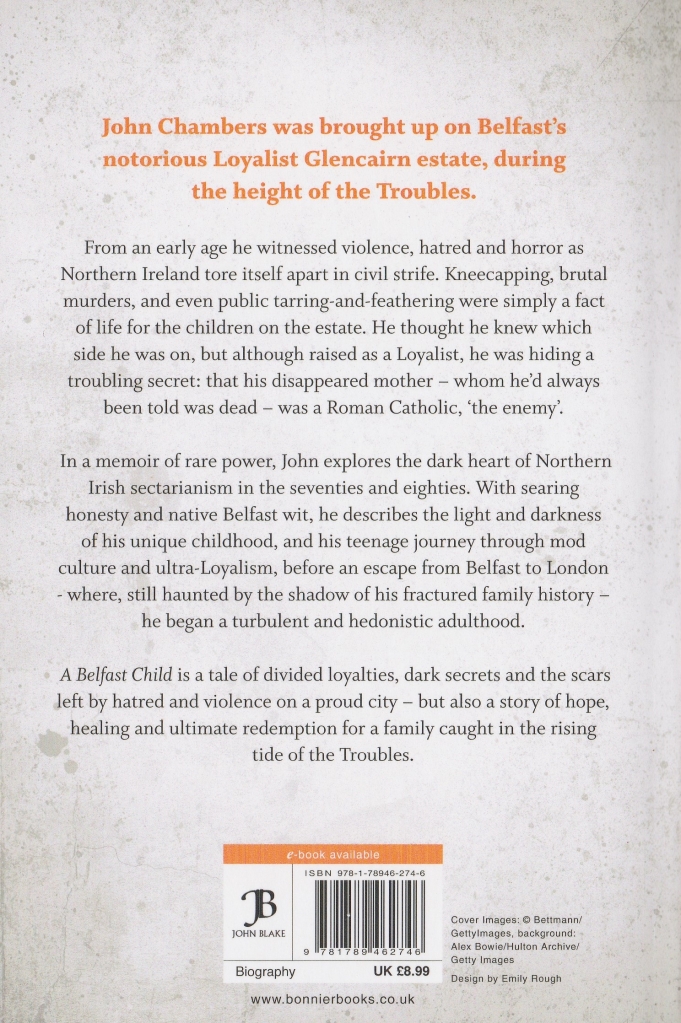

There were some high points during this period and after years of toying with the idea of seeing my story in print I finally managed to get a book deal and realised one of my long-held dreams. Subconsciously I think I was a little uncomfortable with publishing the book whilst mum was alive , although I had completed most of it back in the late 90s and she had read and approved of the early drafts.

As you may suspect this was not a straightforward process and there were many soul destroying bumps and rejections along the way but I persevered and much to my delight the book has went onto be a bestseller. Despite the popular misconception being a bestselling author has not made me rich , far from it and like many I struggle sometimes financially to make ends meet. Having said that I know the book will be my legacy and fingers crossed I’m working on a film script that I hope to sell in the coming years.

Stay tuned.

I will be covering the whole journey from concept to publication of the book in a future post and Princess Diana features in this story.

Life went on and my fragile soul struggled to deal with mums passing but always in the background I had my two sister’s supporting and comforting me from Belfast. Both desperately wanting me to return, and Jean was forever begging me to come home and to be honest I wanted nothing more. I began to feel trapped in England due to the dilemma of my children and the deep roots they had planted here, and I could see no way forward.

But the fates love to toy with the destinies of mortal men and the unpredictability of life weaved by the wicked Norns was about to shake my world to its very foundations and nothing would ever be the same. In the space of twenty four short months I lost three members of my close family, my uncle William, much loved brother in law Richard and the hardest loss of all my beloved big sister Jean. My grief and sorrow were biblical and the pain of losing Jean took me to dark places that hunt me still.

To make things even more difficult during this brutal period my “perfect” marriage of twenty-eight years was falling apart and suddenly I had to adjust to being a single parent and living alone in a life I had grown to detest.

To be completely honest these events are still too raw and painful for me to write about in-depth and I will leave them here for now. but I find the process of putting my thoughts on paper cathartic and will be covering these in a later post.

Oh , I almost forgot to mention in the midst of all this turmoil I was diagnosed with a potential life threatening brain aneurysm and I will cover this also in an upcoming post.

All these events have led me to a crossroad in my life and once again I am seriously considering moving back to Belfast permanently . Although I love England and its been good to me I have nothing left here but my children (and three legged cat) and they both understand and support my desire move back home. Autumn has now flown the nest and is settled with her new fella and yes I approve of him. Jude is a typical grumpy teenager and splits his time happily between his mum and me and as long as we feed him and give him money, he is happy with his lot and for me to move back to Belfast.

But it’s not that black and white for me.

He’s only seventeen and in my eyes still a child, although he thinks he’s a big man! I want to be there for him as he grows and matures and evolves as a young adult and be there to share and support him through the trials and tribulations life throws at him. I want to be there when he has he’s first pint in a pub , ( a regret I never had with my own dad) be there to pick him up when he falls down and be a constant presence in his life. Down the line when my children marry ( or not ) and have their own kids I want to be part of their lives and not a distant grandfather living over the Irish sea they see a few times a year. Also, since Jeans death Belfast has lost some of its magic for me as spending time with her was always a highlight of my trips home and in some ways I would feel guilty moving back when she’s not there.

So what am I going to do ?

Stay tuned and when I make up my mind Ill let you know x

That’s all for now folks, I’m pushing myself to write again as I’ve not put pen to paper in almost two years and I’m a little rusty and out of practice. . So be gentle with me please.

Buy me a beer 😜

Time keep slipping into the future.

Upcoming posts :

The reason I left Belfast.

Book writing process and publication

My movie script, where I’m at

Once upon a time in Northern Ireland, why thoughts and the process of taking part

And much more…