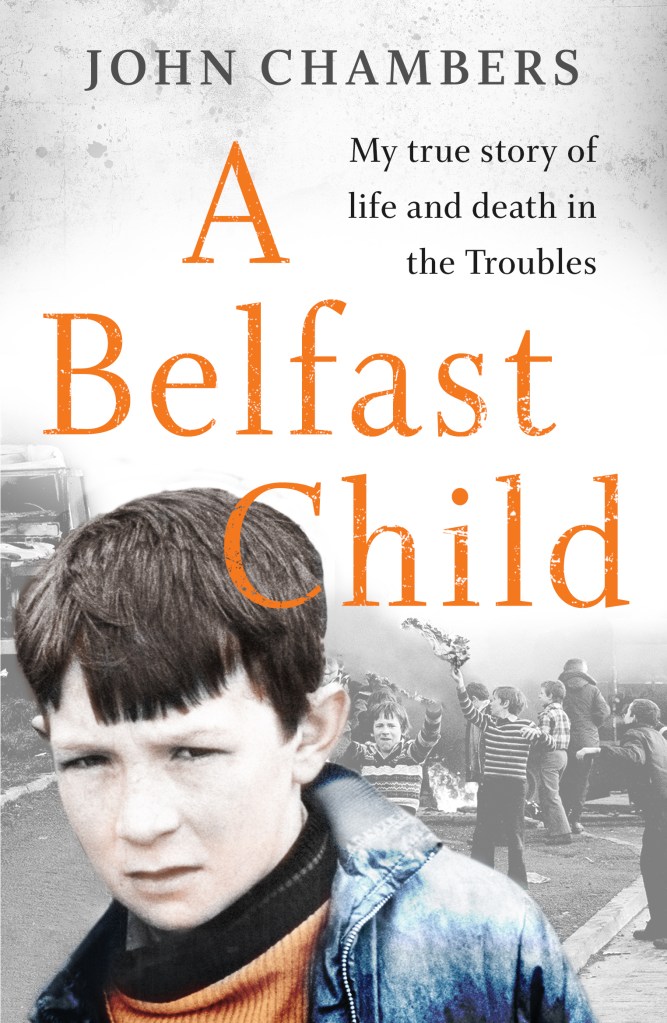

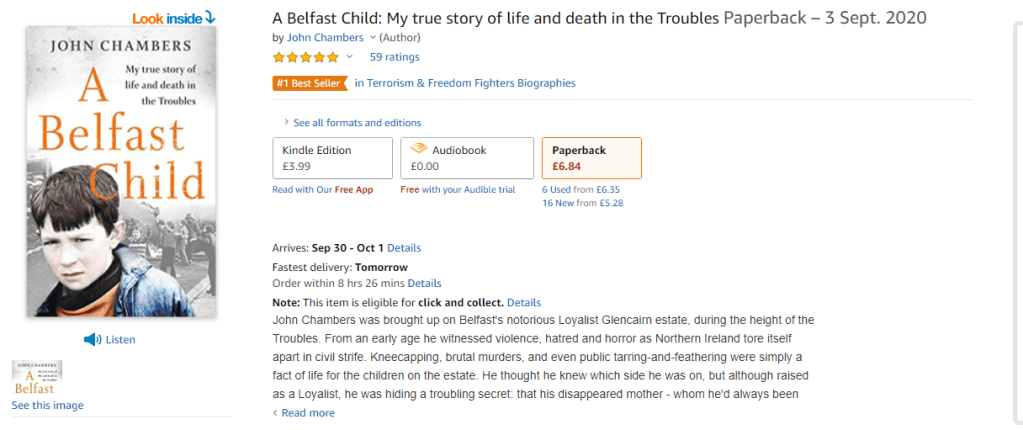

Belfast Child The Movie ?

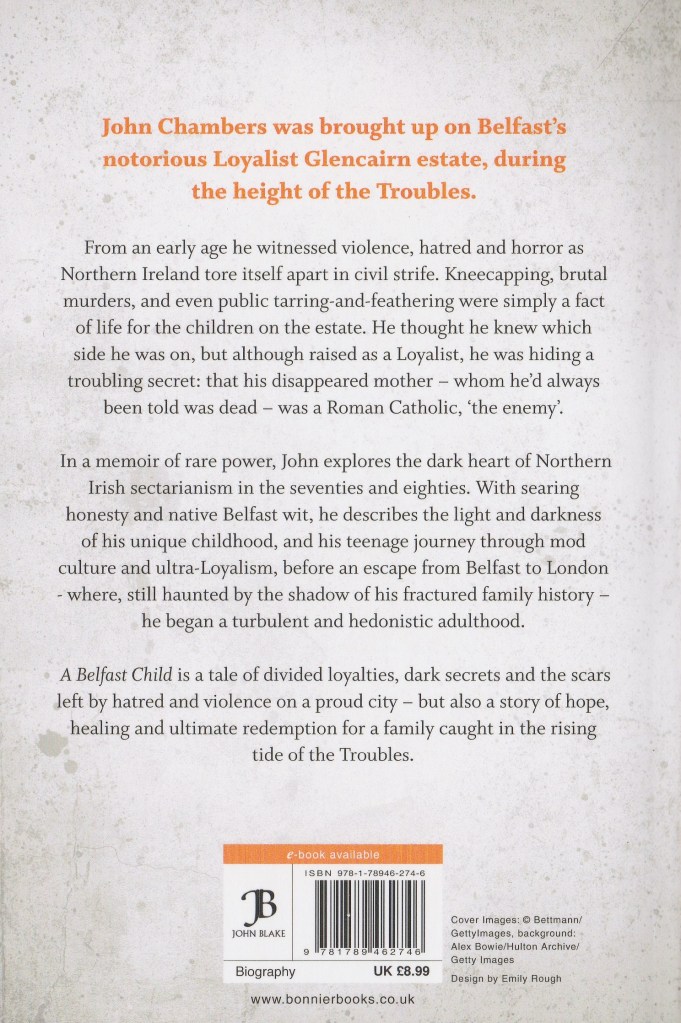

I’m in the process of trying to complete a script based on my number one bestselling book A Belfast Child and to be completely honest I’m seriously struggling and becoming disillusioned with the whole process. Recently I feel like just admitting defeat, throwing the towel in and consigning the idea to the long grass.

But I’m not going to give up – just yet!

Since the book was published (and well before) I’ve been working on a script l based on my story (Philomena meets Trainspotting/Quadrophenia kind of theme) and I completed the first draft a few years ago. I sent this to Northern Ireland screen and some agents and the feedback I received was positive, but they suggested I needed to do some rewrites and changes to make it sellable before submitting it again. At the time I was going through some personal issues including my mum’s soul-destroying long illness and the publication of my book also took precedence, so I put the script on hold for a few years to focus on more pressing issues such as the daily grind of life and surviving all those little obstacles fate loves to throw in my path.

Earlier this year I thought I would give the script another go and have been working on it on and off since. It may surprise some of you to learn that putting together a script is an entirely different beast to writing a book and to be completely honest I’ve been really struggling with tweaking and amending it and its doing my head in !

I’ve reached out to a few folk in the industry and for one reason or another they cant commit to helping me complete this project. I’ve had meetings with established scriptwriters and producers and although they love the idea and praised the story none of them seem to have the time or resources I need to see this through to completion.

Also the success of Belfast the movie has put some of from taking up my story as they feel the market for Trouble’s themed stories has been saturated over the years and another Belfast story would be hard to place in the market. Obviously, I disagree with this and although I thought Belfast was a great movie it sugar coated the brutal reality of what life was really like back then whereas I feel my story/script incorporates the raw horror and unceasing violence that dominated our daily lives in the ghettos of Belfast and beyond and the legacy of the Troubles that still hunt us to this day. There was also much teenage madness and laughter which offered us some brief moments of escape from the violence all around us.

I’m waffling now so let me get to the point !

I have come to the conclusion in order to move my idea forward I need to bring in some professional help and with that in mind Im in the process of finding and engaging the services of a well-established script consultant and further down the line a script editor. These guys are in high demand and don’t come cheap but if I’m to have the best chance of seeing my script through to completion with professional input and guidance I’m looking at a fee of between £5000 – £10000 and possibly more down the line.

Despite popular belief being a bestselling author has not made me a millionaire (yet) or indeed anywhere near it and like many I face the same financial struggles that are the curse of the cost of living crisis we are all experiencing. But I have a long-held dream to see my story on the big screen and I am focused on pursuing this until I have achieved that aim. It took me almost twenty years to finally see my book in print and through all the ups and downs and soul-destroying rejections I persevered until one day a publisher took me onboard and the rest is history as they say. It was a long and hard process and there were many false starts along the way, but I eventually got there. I never give up on that dream until it became a reality, and I am going to apply the same determination and dedication in my quest to complete my screen play and see it on the big ( or small) screen one day. Hopefully within the next few years as Im getting old and my time is running out…

So that’s my mission statement and Ill be keeping you all updated via my blog and Twitter ( I just can’t get use to calling it X ) as and when I have something to share . It’s going to be a pain raising the fee for the services I need but one way or another I know Ill get there eventually.

If you’d like to be part of my story and are feeling wildly generous and excited about seeing me succeed and my project developed you can contribute towards the costs by clicking the donation button below.

If and when the movie comes out Ill give you all a mention 😜

Click donation button below to be a part of this awesome journey .

Life was hard in the mean streets of Loyalist Belfast during the Troubles. Still is for many .

Extracts from my book A Belfast Child.

As I’ve said, the spell in gaol was towards the end of a long period of joyriding, shoplifting and drug-taking, some of which I was lifted for, many others that I got away with. In the 1980s, stealing cars and joyriding was almost a full-time occupation for many of Northern Ireland’s teenage males , especially in the Loyalist and Republican-controlled ghettos. There was always a danger that an untrained driver would crash, accidentally or deliberately, into an army checkpoint and be shot dead, and this happened on multiple occasions during the Troubles. I wasn’t confident enough to drive, but I was a regular passenger in cars that had been stolen by my mates in Belfast city centre and driven at high-speed back up to Glencairn, where they’d be burned out.

This was the scenario one such Saturday night, when we jacked a car just for the hell of it. The experts could be in there with the engine started in five seconds flat, and there was little chance of being caught red-handed. We belted up the Crumlin Road, not bothering ourselves with red lights or pedestrian crossings, and celebrated reaching our home turf with a screeching handbrake turn, perfect in every technical sense except that it ended with a side-on smash into a nice new Opel Ascona car parked on the other side of the road.

None of us were hurt, but as we stared at the damage we’d inflicted on the Ascona we realised we’d committed a crime that could see us all shivering in fear as, one-by-one, our kneecaps were removed by a bullet from a Browning pistol. The car we’d just hit belonged to a top UDA man, a guy known to all of us as a character who took no nonsense, especially from a gang of hoods. Sensibly, we bolted from the car and ran as fast as our legs could take us.

Unfortunately, Glencairn is a small place and word quickly reached the UDA as to the identity of the joyriders. The following day we all received the inevitable summons to the community centre, where the paramilitaries were waiting. To say we were shitting it is an understatement.

‘Don’t even fuckin’ think of denying it!’ screamed the enraged commander, when we tried to do just that. ‘If youse think you’re gonna get away with this, youse are more stupid that ye look!’

With that, he pulled a pistol from his waistband. A couple of our gang started to cry. I could feel my balls disappearing into my stomach as I thought about the prospect of hobbling around the estate for the rest of my life.

‘Now,’ he said, brandishing the pistol in our faces, ‘did ye smash my car up or didn’t ye?’

Miserably, we nodded in unison. Our fate was sealed. Whatever happened to us next, we’d just have to accept. It was simply part and parcel of life in Loyalist West Belfast back then.

The commander looked us up and down, this group of shuffling, shaking, sniffling boys. Perhaps something about our pathetic appearance softened his heart. Maybe he realised that we’d not meant to do what we did, that it was an accident that only affected him personally, not the Loyalist movement as a whole.

‘Here’s what’s going to happen,’ he said, after watching us sweat for a minute or so. ‘I’m going to buy a new car, and every Saturday youse are gonna come up to my house and clean it inside and out. And if it’s still dirty, you’ll start all over again. You got that?’

I couldn’t believe what I was hearing. He was letting us off! Well, not quite, but washing a car was a whole sight easier than walking with a missing kneecap. We glanced at each other in shock, barely suppressing our smiles of relief, – until the commander banged his fist on a table.

‘And if I ever catch youse joyriding again,’ he said in a menacingly low tone, ‘there’ll be no question of what will happen to you. Got that?!’

We trooped out like a gang of monkeys released from a cage. And two Saturdays later we were at the commander’s house armed with buckets, sponges and cleaning liquid. After we finished, his was the shiniest car on the estate.

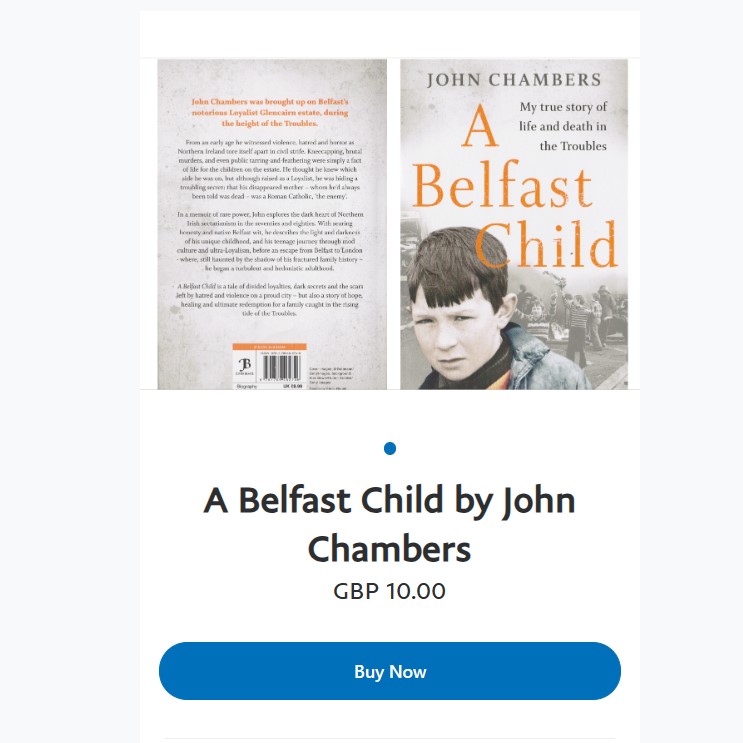

You have been reading extracts from my No.1 Bestselling book. If you’d like a signed copy see below. Ive got a special offer on this weekend . Only £10.00 plus free postage –

Belfast Mods – In the 80s we give Peace a chance !

Becoming a mod in the early 80s during some of the worst years of the Troubles was a life shaping moment for me and for the first time ever I began moving away from the paramilitary run clubs and discos of my youth and meeting and socialising with my catholic counterparts in the city centre and beyond .

To be honest this was a real eye opening epiphany for me.

Prior to this and throughout my early life and teens I had been nurtured and raised exclusively within the loving tightknit tribal communities and social structures of the Shankill and surrounding areas. My tiny loyalist world was dominated by the Troubles and the so-called Peace Walls that separated our two warring war weary tribes. Like those around me my whole life and being was built on my pride in my unionist culture and British identity . Back them paranoia between Catholics and Protestants was off the scale and as a kid growing up when and where I did I couldn’t differentiate between ordinary Catholics and republican killers. Such lines were blurred in my little loyalist world, and like my peers who also grew up in the ghettos of Belfast I knew no different. But as I grew older and wiser my myopic view of Catholics gradually changed and this was largely due to me becoming a mod and starting to spread my wings for the first time and explore the teenage pleasures other parts of my city might offer. Music truly is a universal language and for me it was a glorious unifying force that broke down the barriers that had held me back thus far and I was ready to embrace it all and party like never before.

What follows is one of the Mod chapters from my book A Belfast Child. See below on how to get your hands a personally signed copy.

Chapter 12

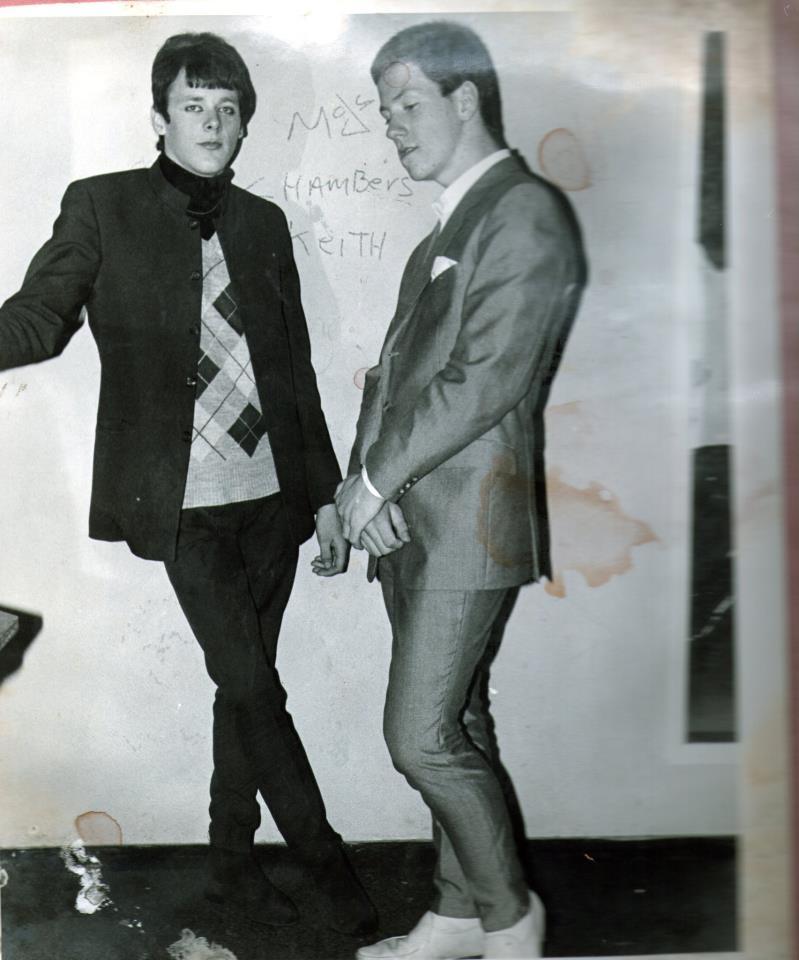

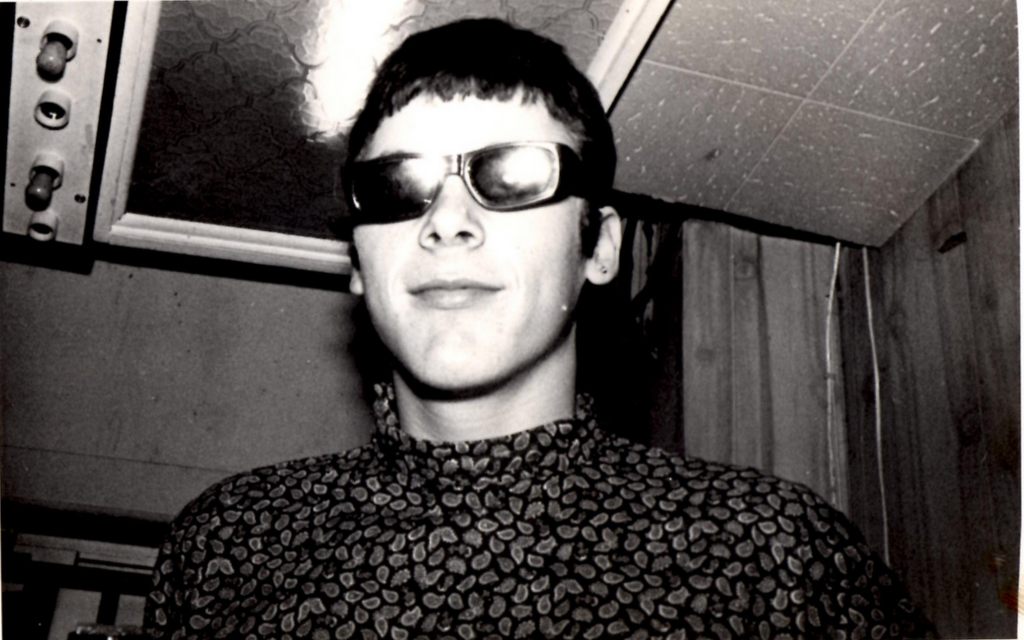

Me as a cool mod

Owning the scooter meant I no longer had to wait for buses or black taxis that never arrived, or risk walking through heavily Nationalist areas where my eyeliner and beads would attract very unwelcome attention. It was bad enough walking down the Shankill in all the clobber; skirting the Ardoyne or Unity flats as a Loyalist in a paisley-patterned shirt was sheer suicide.

The Merton Parkas ‘You Need Wheels’ TOTP (1979)

Of course, Mod as a movement wasn’t confined to us Prods. We knew that a sizeable number of Belfast Catholics were also into the clothes, the music and the drugs. I’m guessing that not many of them wore Union Jack T-shirts or had red, white and blue roundels painted on their parkas like we did, but aside from that they were just the same as us.

Jacqueline’s photographs show gangs of boys and girls congregating in several spots around Belfast and no one has ‘Catholic’ or ‘Protestant’ tattooed on their forehead. All we see is a gang of young kids smiling, laughing and having fun together – just as it should be when you’re that age.

Belfast Mods outside the city hall 1980s

Mod took no notice of religion. There was no place for hatred or division among the scooter boys and girls who gathered on a Saturday afternoon by the City Hall, or drank in the Abercorn bar in Castle Lane (which, ironically, was the scene of an infamous IRA bombing in 1972 that killed two young Catholic women and injured 130 other innocent people – a particularly disgraceful act in a terrifying year). Sectarian insults and deep-rooted suspicions were put aside when Mods from both sides of the fence danced at the Delta club in Donegall Street or drank strong tea and smoked fags in the Capri Cafe in Upper Garfield Street. When Mods gathered, there was no time for this kind of talk. Hanging out, being cool and looking sharp were the only things Mods were interested in. For those moments, all the violence and oppression and misery were put aside.

Me on the front of a book about Belfast mods

I say ‘put aside’ because putting aside such ingrained beliefs was about as much as anyone could do in those deeply divided days. You couldn’t forgive or forget, not when there was so much senseless killing happening on both sides. In my view, every outrage committed against our community had to be avenged and if I heard about IRA men killed by the Brits or the Loyalists I celebrated as happily as I’d always done.

And yet . . . .there was still the lurking knowledge that a part of my background was linked to the very community from which the IRA and its Republican offshoots came from. Allied to that, I was now one of those Mods who were mixing freely with Catholic boys and girls in the city centre, dancing the night away with them and sharing cigarettes, weed, pills, whatever, in various bars and cafes. My heart was as Protestant and Loyalist as it always had been but by now my head was telling me that under the skin, we poor sods who were stuck in the middle of a war zone were all the same. Being Belfast kids, we only needed a couple of seconds’ conversation to find out where someone was from and what religion they were but when the Mods came together this didn’t seem to matter. A person’s religion was becoming irrelevant to me , but I still hated the IRA all right.

At first I was nervous. I’d encountered Catholics before, of course, but only when I was younger. Now I was hanging around with Catholic kids who, like me, were already associating with paramilitary groups. Involvement in the UDA, UVF, IRA, INLA, etc was born of tradition. It was what you did if you came from Glencairn, Ardoyne, Shankill, Andersonstown. But when you pulled on your mohair suit – and, being newly minted I had a few of these hand-made, so I claim to be the best-dressed Mod in Belfast at the time – and fired up your Vespa, your political associations were put aside. We just didn’t talk about any of that stuff, and it was better that way.

Squire – It’s a Mod Mod World

In my childish loyalist world, I couldn’t tell the difference between ordinary peace craving Catholics and IRA killers, such lines were blurred in my childhood world. I was a product of the tribal community that I had grown up in and republicans were our sworn enemies. But the more I got to know Catholics, the less I hated them. I was no longer lumping them all into one big bunch of terrorists. The boys I was talking to as we sat astride our scooters by the City Hall, checking out each other’s suits, shirts, shoes and girlfriends, had had similar experiences to me. I knew that, and so did they. But on those precious Saturday afternoons, when we all felt young and vibrant and just happy to be alive, none of that mattered. We ignored the madness going on around us as best as we could and yet there was always the possibility of being caught up in a bomb or gun attack from Loyalist or Republican terrorists.

The Jam – A Bomb in Wardour Street

I became friendly with lots of Catholic Mods, including Bobby from the Antrim Road, who became a firm friend. I also hung out with Keith from the Westland and we spent a lot of time together. And in particular Zulu and Tom, two Mods from Ardoyne. One night they invited me up to a club they regularly frequented in their neighbourhood. Like many Loyalist and Republican clubs and bars it had a wire cage around the perimeter and doormen always on guard in case of an attack, which could happen at any time.

All my instincts told me not to go; it was in the heart of Ardoyne, the Catholic enclave bordered by Protestant West Belfast and one of the IRA’s most important heartlands. For a Prod, it couldn’t be any less dangerous. I imagined how ironic it would be if I was drinking in a Catholic area with Catholic friends and the UFF or UVF attacked the place and I was killed. My crazy side, however, ignored all that and, pilled-up and cockily confident, I fell in line behind Tom and Zulu and entered the club.

The three of us stood by the bar in our gear, chatting away ten to the dozen. After I while, I realised that a group of older men on the other side of the bar were staring at me. All the while I knew I should be winding my neck in, keeping my head down and saying very little. By now, though, I was aware I’d already said too much.

Zulu and Tom had already noticed. Tom nipped to the jakes for a pee and on the way back one of the men stopped him, looked over at me and whispered something in his ear. The smile on Tom’s face froze as he received the message.

‘See those wans over there,’ he said as he resumed his position at the bar. ‘They reckon they can tell you’re a Prod.’

‘Fuck, I knew it,’ I said. ‘They’ve been eyeballin’ me since we walked in.’

My stomach had turned to water. There was no knowing what these hard cases would do if they took a hold of me.

‘Here’s what’s gonna happen,’ said Tom. ‘You and me will slowly make your way to the back door. Zulu’ll keep these fellas talking, then go to the jakes. Then he’ll climb out the window. OK?’

I wasn’t in a position to argue. The plan went smoothly and within minutes we were out of the door and away as fast as we could. We soon realised that mixing in the city centre on a Saturday was one thing; doing the same in our neighbourhoods was asking for big trouble, and I doubt we’d have got away so easily in Glencairn or Ballysillan.

The Who – Get Out And Stay Out

But as usual I was up for anything and many times I ignored the risks involved, putting myself in real danger. Once I was at a party up the Antrim Rd and a gang of wee Provies came in, asking everyone what religion they were. I lied through my teeth and said I was a Catholic from Manor Street , which was half true as I had been living there at the time. Another night I met a very cute and sexy Mod girl who made a beeline for me and made it clear that if I were to come back to her flat we would have a very good time indeed. I didn’t need a second invitation and soon we were in a taxi, speeding through Belfast with a nice handful of pills in my coat pocket.

The Who – The Real Me

She wasn’t wrong, we had a lot of fun in her flat that night. By the time I’d dragged my head up from the pillow the following morning she’d gone off to work. I lurched into the kitchen, made myself a cup of good strong Nambarrie tea and helped myself to the rest of her loaf of bread. After an hour of mooching about I opened the curtains and looked out at the view. Immediately, a horrible realisation dawned. I was somewhere up in the Divis Tower, a grim but iconic high-rise building in the middle of the fiercely Republican Divis Flats. Many people had been killed, injured or kidnapped within the vicinity of this place, including Jean McConville, a Protestant woman who converted to Catholicism for the sake of her husband. She had ten kids, and her only crime was to help a wounded soldier. For that, she was taken away from her family and murdered by the IRA.

See: Jean McConville

Quietly, I left the flat, gently shutting the door behind me. I made my way down a series of piss-stained stairways, avoiding the strange glances of a few women going in the opposite direction. The bleakness of this place was indescribable; the houses up on Glencairn were bad enough but this was truly a horrible, dangerous and dirty dump. With as much calm as I could muster I left the estate, not looking left, right or behind me, and walked the half-mile or so towards the city centre, where I had a much-needed Ulster Fry to celebrate yet another escape from Republican West Belfast.

Even so, my associations with Catholic boys and girls were becoming ever closer. A very young Catholic boy with a huge passion for music was DJing down the Abercorn and we all got to know and respect this kid who was barely out of school. His name was David Holmes and he went on to become one of the world’s foremost DJs, producers and re-mixers. It’s amazing to think that these early experiences in the Mod clubs and cafes inspired him to become the success story he is today.

Me and David Holmes

Meanwhile, I’d gone from chatting to Catholics to actually dating them. I met a girl called Kathy who lived a couple of minutes from the Royal Victoria Hospital along the Falls Road. She was small and very pretty and from the moment we met we had great banter together. She was also a trained hairdresser and would cut my hair for nothing, which was also quite appealing. She could have been the one for me to settle down with, but I was young and had ants in my pants and didn’t want to be tied down at the time. Pills and parties were my thing, not tea and nights in front of the telly. Kathy understood this and we were both in it for the craic.

The Jam – When You’re Young

I didn’t think about her being Catholic. Well, not much. The issue would only arise when we wanted to visit each other’s houses. From the off, Kathy was honest with her parents about the fact she was dating a Protestant and they seemed to be fine about it. We got on well and it was never spoken about, though no doubt that as parents they had their concerns. I liked them too, but I wasn’t entirely comfortable spending time in the Falls Road area. Although neither of us told anyone outside of the Mod scene that we were dating someone from the ‘other side’, these things could become common knowledge very quickly, as I’d previously discovered.

I was always fearful when Kathy wanted to come up to Glencairn. I made sure nobody was in the flat whenever she came and I told no one she was a Catholic. Kathy had a car (probably another attraction for me) and I remember one night the two of us driving up the Shankill towards Glencairn when we came to a sudden stop. We’d run out of petrol but luckily I knew there was a garage a few hundred yards up the road. Without thinking, I grabbed a battered metal petrol can from her boot and made my way up the road. I filled the can, paid up and strolled back to the car. I arrived to be greeted by a very white-faced Kathy, huddled in her seat so that she was almost under the driver’s wheel.

‘S’matter wi’ you?’ I said. ‘I’ve only been a couple of minutes.’

‘You fuckin’ eejit!’ she snapped back. ‘Didn’t ye think? Wee Catholic girl on her own up the Shankill ?

I hadn’t thought, but when I did I felt sick to the stomach. If, for some reason, her identity had been discovered, she’d have been in deep shit. Even young women were shown no mercy if they turned out to be Taigs in the wrong neighbourhood. When we finally returned to my flat, she was still shaking with fear.

The proximity of Catholic kids sometimes brought me back to the dark place – the unspoken secret that rattled around my mind and, at low points, threatened to overwhelm me completely. These crashes would usually happen when I was coming down off whatever I’d been throwing down my neck the previous evening – booze, pills, powders. I’d sit in my flat alone and think about my family – the father I’d adored and lost so early, the mother I’d never known who was out there somewhere, but who wouldn’t or couldn’t get in touch with us. My sisters, bringing up families without the help of proud grandparents. And to top it all, the endless cycle of violence and misery that was part of the fabric of everyday life in Northern Ireland. ‘Today, an RUC man was killed by a car bomb at his home in Portadown . . . Two masked men broke into a house in North Belfast and shot dead a Sinn Fein Councillor . . . ..A Protestant man on his way to work in Newry last night was the victim of a sectarian shooting . . . Two children were badly injured when a bomb went off in central Londonderry. No warning was given . . . ..’ On and on it went:, murders, bombing, riots, robberies, protests, kneecappings, torture, imprisonment the hedonism and escapism provided by the Mod movement in Belfast was grand while it lasted, but the relentless tide of horror and misery washed it away, day after day after day.

Belfast mods

Can you spot me ?

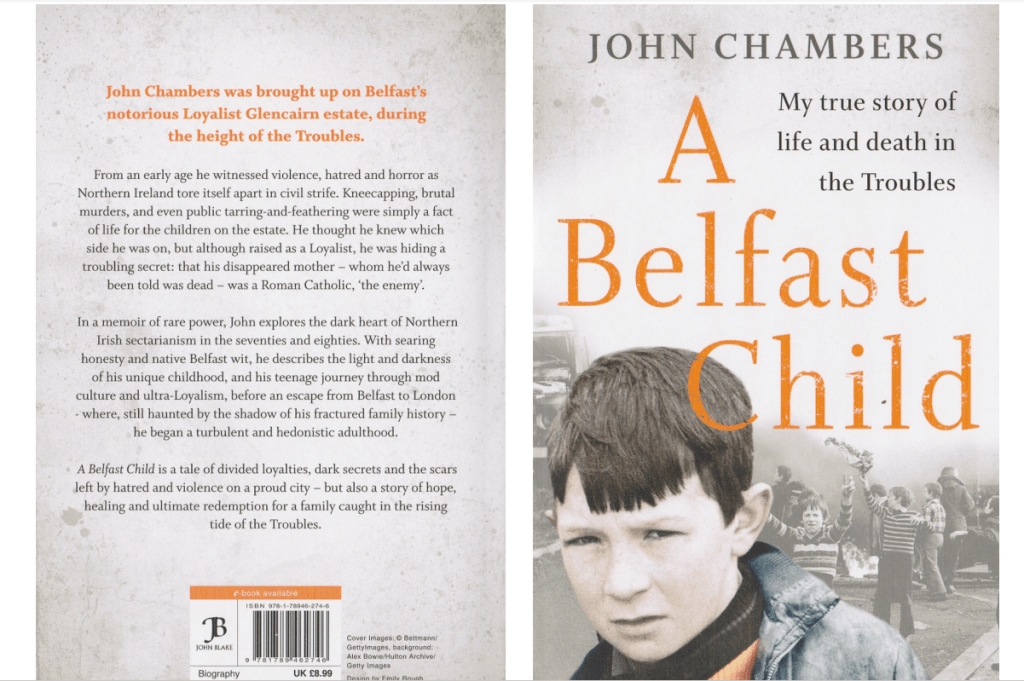

You have been reading extracts from my best-selling book A Belfast Child.

Want a signed copy ?

If you’d like a personally signed copy ( £12.50 , including postage ) click the link above or below to buy or send me an email and Ill pop over a link : belfastchildis@googlemail.

Buy a signed copy £12.50 including postings and packing : A Belfast Child signed copy

Before you go

Is it Time to Panic ?

12 June 2023

Well, it’s a big day for me tomorrow and to be honest I’m getting a little nervous, and a teeny-weeny tad stressed about it all. But I suppose that is all perfectly normal. Right?

It’s not helping that there’s a thunderstorm brewing outside and I’m finding hidden meaning and dark portents as I listen to the thunder rumbling gently in the in the distance. Also reading through the notes on the procedure I’m going through (cerebral angiogram) I came across the list of the potential complications and this one totally freaked me out.

Procedures involving the blood vessels of the brain carry a small risk of stroke. This can range for a minor problem which gets better over time to a severe disability involving movement, balance, speech, and vision.

Fook me !

Time to have a word with m myself.

Stop it!

Having said all that I’ve been aware of this suspected aneurysm since November last year and I decided then I wasn’t going to let it get me down or dwell on it as that wouldn’t change a thing and I would end up driving myself up the wall with worry and I just couldn’t be arsed with that. So I buried my head in the sand and awaited the hospital appointments and here we are.

The doctors advised me to cut down on smoking and drinking and needless to say I’ve largely ignored both these self-serving guidelines. I know. But I’ve been smoking and drinking for forty odd years and these destructive lifelong habits are hard to break free from and Im a creature of habit and hate change.

To be fair I’ve not had a drink since Saturday night and I’ve cut down my smoking over the past few days and believe me that took some self-discipline. My kids were appalled at how much I was captured on film smoking during the Once Upon a Time in Northern Ireland programme. Ive promised them Im going to try and commit to giving up but just just yet…

Anyway, I’m nil by mouth tonight and I have to be at the hospital by seven tomorrow morning so Im going to chill by the telly and have a calm relaxing evening and then early to be bed. If I get a positive outcome tomorrow I’l be dancing in the street and having a wee ice cold beer to celebrate.

Thanks to all my wonderful Twitter friends and the many who follow my blogs for all the love , support and comforting words. I am truly touched.

As the wonderful Doris Day once sang Que Sera, Sera

What is a cerebral angiogram?

A cerebral angiogram is a diagnostic test to examine the blood vessels in the brain and neck using X-rays and dye. The dye is injected through a plastic tube called a catheter, which is inserted into the arm.

Plan: Cerebral digital subtraction angiogram (DSA) to evaluate left ICA for suspected aneurysm/infundibulum.

- 6 People lost their lives on the 6th January between 1980 – 2001 . read their stories here :

- Merry Christmas to all my friends out there X

- A singed copy of my book for Xmas ?

- I need some help folks 😜

- Ireland’s Bloody History – Rathlin Island Massacre July 1575

Don forget to follow me on Twitter @bfchild66

And subscribe to my blog

Testing something

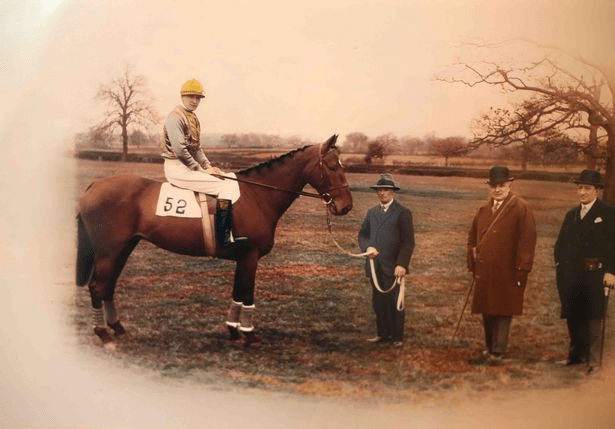

Tipperary Tim – astounding 1928 Grand National winner at 100/1 & a proud resident of Glencairn !

Tipperary Tim

Astounding 1928 Grand National winner at 100/1 & a proud resident of Glencairn !

Tipperary Tim (foaled 1918) was an Irish Thoroughbred racehorse that won the 1928 Grand National. He was foaled in Ireland and was a descendant of the undefeated St. Simon.

Tipperary Tim was owned by Harold Kenyon and trained in Shropshire by Joseph Dodd. He was regarded as a fairly slow horse, but one who rarely fell. Tipperary Tim was a 100–1 outsider at the 42-runner 1928 Grand National, which was run in foggy conditions and very heavy going.

A pile-up occurred at the Canal Turn jump that reduced the field to just seven horses. Other falls and incidents left only Tipperary Tim and the 33-1 Billy Barton in the race. Billy Barton struck the last fence and fell, leaving Tipperary Tim to win – Billy Barton’s jockey remounted and finished a distant second (and last). The incident led to controversy in the press who complained that a Grand National should not be won merely by avoiding accident. It led to changes to the course with the ditch at Canal Turn being removed for the following year’s race. Tipperary Tim enjoyed no real success in other races.

Early life

Tipperary Tim was foaled in Ireland in 1918, his breeder was J.J. Ryan. Tipperary Tim’s sire was the British horse Cipango and his dam was the Irish horse Last Lot, his grandsire was the British horse St Frusquin (who had been sired by the undefeated St. Simon) and his damsire was British horse Noble Chieftain. He belonged to Thoroughbred family 19-b.

The stud fee paid for Cipango was just £3 5s (equivalent to £153 in 2020). Tipperary Tim was named after a local marathon runner, Tim Crowe. He was a brown-coloured gelding.[1] Tipperary Tim had been sold as a yearling for £50 (equivalent to £2,349 in 2020) and was said to have once been given as a present.

Tipperary Tim came into the ownership of Harold Kenyon. He was trained in Shropshire by Joseph Dodd who noted that “he never falls”. By other reports he was capable of only one pace, and that a relatively slow one. Tipperary Tim was tubed, that is he received a permanent tracheotomy, with a brass tube halfway down his neck to improve his breathing. He was stabled at Fernhill House in Belfast. Tipperary Tim competed at Aintree in the November 1927 Molyneux Steeplechase.

1928 Grand National

Tipperary Tim was entered into the 1928 Grand National at the age of 10 years. He was ridden by amateur jockey Bill Dutton, a Cambridge-educated solicitor from Chester, who had left the profession to pursue horse-riding. Tipperary Tim was a 100–1 outsider and Dutton later recalled that a friend had told him before the race:

“you’ll only win if all the others fall”.

The field in 1928 was the largest to date with 42 runners starting the race. The going was very heavy and there was a dense fog. There were three false starts, after which the broken starting tape had to be knotted together. On the first circuit of the Aintree track the leader, one of the favourites, Easter Hero, mistimed the Canal Turn jump.

Rising too early he was stranded briefly on the fence before becoming trapped in the ditch, which preceded it. The next three horses, Grokle, Darracq and Eagle’s Tail were brought down by Easter Hero. Of the remaining runners (22 remained in the race), twenty refused to jump the fence. The pile-up was described by racing historian Reg Green as “the worst ever seen on a racecourse”.

Only seven horses with seated jockeys emerged from the incident to continue the race. One of these was Tipperary Tim as Dutton had chosen to take a wide route around the outside of the course, avoiding hazards that had brought down other jockeys. Because of the fog the majority of the audience were unaware of the incident at Canal Turn.

By the second jumping of Becher’s Brook only five horses remained in the race with Billy Barton leading ahead of May King, Great Span, Tipperary Tim and Maguelonne. Maguelonne was still trailing at the first fence following Valentine’s Brook where it fell. May King fell shortly afterwards before Great Span lost his saddle and rider, leaving only Billy Barton, who started with 33–1 odds, and Tipperary Tim.

Billy Barton had led the race for 2.5 miles (4.0 km) until the last fence where Tipperary Tim drew level. The riderless Great Span was between them and may have slightly hindered Billy Barton. Billy Barton struck the final fence with his forelegs and fell, dismounting his rider, Tommy Cullinan. Tipperary Tim came in first, with a time of 10 minutes 23.40 seconds, he was closely followed by the riderless Great Span; a remounted Billy Barton came a distant second and was the last to finish.

With only two horses completing the race the 1928 Grand National set a second record, for the fewest finishers. Tipperary Tim was the only horse to have completed the race without falling or unseating its rider. Kenyon received prize money of 5,000 sovereigns as well as a cup worth 2,000 sovereigns. Tipperary Tim became one of the biggest outsiders to win the Grand National, only three other horses with odds of 100–1 have won the race: Gregalach in 1929, Caughoo in 1947 and Foinavon in 1967.

There were scathing reports in the press, which described the race as “burlesque steeplechasing”, and many writers stated that a Grand National should not be won merely by avoiding an accident. The race inspired some to become involved in the sport. The future horse racing commentator Peter O’Sullevan laid his first ever bet on Tipperary Tim and cited it as the start of his life-long connection with racing. The Pathé footage of the race inspired a young Beltrán Alfonso Osorio to aspire to a career in racing. He became an amateur jockey who rode at the 1952 Grand National and others thereafter .

The World’s Greatest Race (1928)

The success of Tipperary Tim led to larger fields in the following Grand Nationals. According to racing historian T. H. Bird “everyone who owned a steeplechaser that could walk aspired to win the Grand National”, leading to more entries which, Bird lamented, “cluttered” the field with “rubbish”.

The 1929 Grand National started with 66 runners, including Tipperary Tim who, despite his success the previous year, remained a 100-1 outsider. The ditch at the Canal Turn had been removed before this race, as a result of the incident in 1928. Tipperary Tim fell during the 1929 race and did not finish. The horse enjoyed no real success aside from his 1928 Grand National win.

Main source Wikipedia

Grand National News : Tipperary Tim

The Mirror : The amazing story of Tipperary Tim and the Grand National’s biggest ever upset

If you’ve read my book you’ll know I write about this legendary horse and my childhood spent playing in and around Fernhill House.

See below for extracts.

Dad pointed to an old and imposing big house up the top end of a driveway in Glencairn Park. ‘This is Fernhill House, and it’s where Lord Carson inspected the UVF men before they went off to war.’

‘To fight the Provies?’ I asked. I was only six, but already the language of the Troubles had begun to filter through my vocabulary. The ‘Provies’ were the Provisional Irish Republican Army – the enemy currently engaged in warfare with the British Army and bombing buildings in Belfast, Londonderry and many other places, killing soldiers, police officers and innocent civilians alike, and the UVF stood for the Ulster Volunteer Force, which was better known as a Loyalist paramilitary group during the Troubles.

‘Nah,’ said Dad, laughing, ‘not them. The UVF went off to fight the Germans in the First World War. Have you heard of the 36ththirty-sixth?’

I hadn’t, so Dad gave me a quick history lesson. The 36th Ulster Division were the pride of Protestant Belfast (although many Catholics fought in it too) and distinguished itself at the first day of the Battle of the Somme. Dad used to quote the words of Captain Wilfred Spender, who watched as the 36th Division went over the top: ‘I am not an Ulsterman but yesterday, the first of July, as I followed their amazing attack, I felt that I would rather be an Ulsterman than anything else in the world.’

Even today, I feel an enormous sense of prised pride when I hear those words.

I loved these kinds of stories, especially about our grandfathers and great-grandfathers who’d been so brave in the face of almost certain death. In fact, my great Uncle Robert fought and tragically died two weeks before the end of the war.

‘Are the UVF still around, Da’?’ I asked, wide-eyed. I hoped they were, as I recalled the rioting and burning I was told was the work of Catholics out to get us.

‘So they are, son,’ Dad said, ‘but hey, let’s not talk about all that now. C’mon with me now and we’ll get a pastie supper.’

I jumped up and down with delight. Pastie suppers were (and still are) my favourite. Only Northern Ireland people can appreciate the delights of this deep-fried delicacy of minced pork, onions and spuds, all coated in delicious batter, with chips on the side and a Belfast Bap (a bread roll).

As we walked from the brow of the hill down to the chippy, Dad told me a few more stories about Fernhill House. It was owned by a family called Cunningham, he said, and it had stables attached to it. In one of these was housed a racehorse called Tipperary Tim. and according to legend, the horse’s jockey, William Dutton was told by a friend, ‘Billy boy, you’ll only win if the all the others fall.’

‘Sure enough,’ said Dad, ‘yer man Dutton took the horse into the Grand National in Liverpool and all the other horses fell down. And so Tipperary Tim won the race.’

‘That’s amazing!’ I shouted. ‘Does he still live in the stables? Can we go and see him? Please, Da ’ . . .’

In response, my dad laughed. ‘You’re a bit late, son,’ he said., ‘the race was won in 1928!’

In time, Fernhill House and the surrounding area would become my childhood playground and I’d spend hours playing in the park and exploring the empty mansion and its cavernous cellars. Years later, when the Loyalists called their ceasefire as part of the Good Friday Agreement, legendary Loyalist leader Gusty Spence and the ‘Combined Loyalist Military Command’ choose Fernhill House to tell the world their war was at an end and offer abject and sincere remorse to their victims.

See below to order a copy.

Click here to buy on Amazon : A Belfast Child by John Chambers

If you would like a signed copy email me for details .

Golden Brown – The Stranglers: Iconic Songs & the story behind them

The Stranglers

Golden Brown

January 1982

Golden Brown – The Stranglers: Iconic Songs & the story behind them

Golden Brown – The Stranglers

“Golden Brown” is a song by the English rock bandthe Stranglers. It was released as a 7″ single in December 1981 in the United States and in January 1982 in the United Kingdom, onLiberty. It was the second single released from the band’s sixth albumLa folie.

See:La folie(album) Track Listing

It peaked at No. 2 in theUK Singles Chart, the band’s highest ever placing in that chart.

In January 2014,NMEranked the song as No. 488 on its list of the500 Greatest Songs of All Time. It has also been recorded by many other artists.

See : 500 Greatest Songs of All Time NME

| SinglebyThe Stranglers |

|---|

| from the… |

View original post 958 more words

fifty skinheads appeared from nowhere, many of them wearing Chelsea and Rangers football scarves and covered in Loyalist and swastika tattoos. These psychos were obviously baying for blood – Mod blood, to be exact.

In the early 80s about thirty of us travelled from Belfast to Liverpool by boat. Then we caught the train down to London and headed straight for Carnaby Street. It felt like a religious pilgrimage and I was hypnotised by the sheer joy of just being there and drinking in the Mod culture it had given birth to.

But my excitement was to be short- lived. As we walked around the legendary area and drank in the super- cool atmosphere, suddenly we heard a massive roar and what sounded like a football stampede, then three terrified young Mods ran past us as if the devil was on their tails.

Belfast Mods 1985

I feature in the documentary , see if you can spot me ?

Time stood still as we waited to see what had scared them and made them take such desperate flight. Then, from a side street, about fifty skinheads appeared from nowhere, many of them wearing Chelsea and Rangers football scarves and covered in Loyalist and swastika tattoos. These psychos were obviously baying for blood – Mod blood, to be exact.

The moment they spotted us they stopped dead and some even grinned at the Mod bounty fate had delivered them. We were in some deep shit and I searched my mind frantically for a way out.

There was only a few of us together at this stage and my heart leaped into my throat as I anticipated the beating I was about to receive. But if nothing else, I was used to brutal violence and two things came to my mind at once.

The first was that I’d experienced many gang battles between Mods and skinheads in the backstreets of the Shankill and Ballysillan, and survived largely intact. But here we were vastly outnumbered, on foreign soil (so to speak), and these guys wanted to rip us apart, limb by limb, while savouring every moment of our agony and humiliation .

I glanced over at the leaders in the front row as they hurled insults and threats. My heart sunk when I noticed some of them had already pulled out weapons, including blades, and were preparing to attack us. This was our last chance. My survival instinct kicked in . I took a deep breath and played my hand.

‘Stay back,’ I said, as calmly as I could to the boys behind me. I was aware that some of our lot were Catholics and, if anything, were probably in far more danger than I was. I stepped forward and, looking for their ‘top boy’, I suggested they all slow down and tell me what the problem was.

The Difference Between Nazi’s and Skinheads | Needles And Pins

You could have heard a pin drop as the fella in question looked me up and down as though I’d just insulted his mother. I could tell he was moments away from lunging at me and all hell kicking off.

Then I heard a familiar accent calling out from the skinhead crowd.

‘Are youse from Belfast?’ said the voice.

There was what seemed like a lifetime’s pause before I answered.

‘Feckin right,’ I said, ‘from the glorious Shankill Road!’

Now I was praying I’d made a good call.

‘That right?’ he replied. ‘So who d’you know?’

I wheeled off a few names of skinheads and assorted bad boys I knew and had grown up with on the Shankill and Glencairn and this satisfied them. We were safe, for now at least. It turned out the guy who spoke, Biff, had grown up in Glencairn, now lived and worked in London and was involved with other Loyalists living in the capital. His crew were a nasty bunch and I pitied those who had the misfortune to come across them, especially if you weren’t a WASP. If they had known some of the Mods present were Catholics, nothing would have stopped them kicking the shit out of me and the others and I silently thanked the gods for delivering us from evil.

My second thought was about the Rangers scarves and the Loyalist/English Pride-style tattoos a good number of them were sporting. An idea started to take shape in my terrified brain. Rangers was the team of choice for much of the Protestant population of Northern Ireland and, along with Chelsea and Linfield, were inextricably woven into the core of our Loyalist culture. I hoped these baying skinheads, or some of them at least, would hold the same pride and love for Queen and country as me and I thought this might just save us.

With the situation defused, I told the others to look around a bit and I’d catch up with them later. I didn’t want the skins chatting with them, finding out some of them were Catholic and undoing all my capital work. They insisted I joined them for a pint or two in the Shakespeare’s Head pub nearby and it must have looked a bit weird: a sixties style Mod, wearing eye liner and a Beatles suit, drinking and laughing with a gang of psycho Nazi skinheads.

SkinheadS & Reggae

But I had spent my life growing up among Loyalist killers and paramilitaries and nothing really fazed me anymore. I didn’t particularly like Biff and his crew but chatting with him over a few pints I realised there was much more to him than the stereotypical skinhead. His English girlfriend had just given birth to their first child and he was ‘trying to get on the straight and narrow’, – whatever that meant.

After a few hours of drinking and snorting speed with Biff and the others I left them in the pub and return to the sanity of my Mod mates. I was to come across Biff and his crew later that weekend, when they and dozens of other skinheads and punks ambushed and attacked Mods coming into or out of the all- dayer in the Ilford Palais. Luckily, I was safely inside, stoned out of my mind and living the Mod dream and I didn’t concern myself with the antics of those fools, though I did have a chat with Biff while grabbing some fresh air and a fag outside.

Safely back in Belfast, we started to plan other trips abroad, specifically to ‘The South’. Enemy territory.

You have been reading extracts from my number one best selling book A Belfast Child.

To order a personally signed copy click the link below

Want a signed copy ?

UK orders only: Order a signed copy , only £12.50 plus free postage

If you live outside the UK please email me and I will provide details on how to order : My email is belfastchildis@googlemail.com

Click here to buy : Order a signed copy , only £12.50 plus free postage

The Story of Skinhead with Don Letts (BBC Documentary)

- 6 People lost their lives on the 6th January between 1980 – 2001 . read their stories here :

- Merry Christmas to all my friends out there X

- A singed copy of my book for Xmas ?

- I need some help folks 😜

- Ireland’s Bloody History – Rathlin Island Massacre July 1575

- Ireland’s Bloody History – Portadown massacre November 1641

- Here’s a complete chapter of my book…

- Norn Iron Olympic Winners 2024 👏👏👏

- Should I Stay or Should I Go – Back to Belfast ?

- (no title)

- (no title)

- Belfast Child The Movie ?

- Life was hard in the mean streets of Loyalist Belfast during the Troubles. Still is for many .

- Belfast Mods – In the 80s we give Peace a chance !

- Is it Time to Panic ?

- Testing something

- Tipperary Tim – astounding 1928 Grand National winner at 100/1 & a proud resident of Glencairn !

The Shankill Butchers…

By age ten I’d heard shots ring out and seen the injuries caused by bullets and beatings. But nothing could’ve prepared me for the scene outside Glencairn’s community centre on Forthriver Road on an overcast morning in October 1976. Before heading to school I polished off my cornflakes and, kicking and protesting as ever, had my face wiped by Granny, who spat on a handkerchief and assaulted my grubby mush with it. ‘Come here, ye dirty wee hallion!’ she shouted as she grabbed me for the unwanted daily routine. Struggle over, I let myself out of the front door and walked the few doors to Uncle Sam’s to call for Wee Sam.

He too had succumbed to the humiliating last-minute face scrub from Aunt Gerry and as we trudged down his garden path and on to the main road through the estate we muttered darkly about our so-called elders and betters.

We’d only walked a few yards when up ahead we noticed a gathering of green and grey Land Rovers and Saracen armoured cars, which we nicknamed ‘Pigs’. That meant only one thing that the RUC and the army were out in force. To the side stood a small knot of onlookers, mostly women on their way to school, the wee ones holding their hands. This group had turned away from the scene and were speaking together. As we approached, we heard murmurs from the women and the occasional shaking of a scarfed head.

‘Fuckin’ hell,’ said Wee Sam, wide-eyed, ‘somebody musta gotten kilt up there. Look at all the peelers around.’

A knot of fear tightened in my stomach as we approached the scene. Despite being on supposedly ‘safe’ Loyalist territory, grim-faced soldiers gripped their SLRs tightly while uniformed police from the RUC spoke into radios and plain-clothes detectives huddled in a group. Judging by the mood hanging over the community centre on this cold, grey morning, we were about to see something unprecedented.

Maybe we should’ve walked on by. But we were just wee boys. Filled with childish curiosity we rubbernecked all the time. ‘C’mon,’ said Sam, grabbing me by the sleeve of my snorkel jacket, ‘let’s see what’s going on!’

We ducked past the group of clucking housewives and right up to a tall soldier in full battledress. ‘Hey mister, what’s happenin’?’ I asked. ‘Is somebody dead?’

The soldier looked down on us, not unkindly. We weren’t his enemy. Maybe he viewed similar aged boys from the Catholic areas of Ardoyne and Andersonstown in a different way, but up here we were the good guys. Supposedly.

‘If I were you two I’d bugger off to school pronto,’ he said, in a northern English voice. ‘There’s nowt to look at here.’

He was wrong. There was something to look at, lying just a couple of yards from where he stood. Behind the soldier’s back, down the grassy bank at the back of the community centre – UDA controlled, of course, and a social gathering point for those in the estate – we saw a pair of shoe-clad feet sticking out at angles from beneath a brown woollen blanket. This covered the undisputable shape of a body, and surrounding it was thick, red, jellified blood. Pints of the stuff that had spread across the grass on which the body lay, creating a semi-frozen scene of complete horror.

‘Jesus!’ I said, stepping back a couple of paces from the soldier. ‘What the fuck happened here?’

‘Never you mind,’ he said. ‘Kids your age shouldn’t be seeing things like this. And watch your language, lad.’

I ignored him and looked again. By now, a typical Belfast morning drizzle had begun to fall, covering the blanket in a fine mist. I craned my neck, and could just about see a tuft of dark, bloodstained hair sticking out of the top. Even at this age I knew that a single bullet, or even a couple of them, couldn’t have created such a mess. Rooted to the spot, I hadn’t noticed that Wee Sam was no longer by my side. I turned to see him talking animatedly to a boy of about our age standing beside his mum and went over. Wee Sam grabbed my sleeve, pulling me into the conversation.

‘Jimmy’s ma says it’s the Butchers who’s done him,’ he whispered, pointing to the body. ‘They carved him up wi’ knives and a’ that. Just cos he’s a Catholic.’

I couldn’t believe it. I knew Provies killed Loyalists, and we killed them. That’s how it was. In my mind that was all fair. We were under siege, and at war. But to have murdered this man just because he was a Catholic? And to have used knives on him, literally carving him up like a piece of meat? I knew something about this was terribly, terribly wrong and I wondered why God in all his wisdom would let such things happen. Was this the point when I started to lose faith in a Saviour who seemed to ignore the suffering of mortal men?

For weeks previously we’d heard whispers across Glencairn about a gang called the ‘Butchers’, or the ‘Shankill Butchers’. We knew they were Loyalist UVF paramilitaries, but seemingly nothing like the uncles, cousins and friends who aligned themselves to the UDA or UVF, collecting for prisoners and running shebeens, illegal drinking clubs that brought in funds. Those we knew to be UDA members, hardened as they were to whatever was going on across Belfast, seemed to be talking about this particular set of murders with a mixture of awe and horror.

As time went on, it became clear that the ‘Butchers’ killings had little connection with everyday Loyalism and more to do with the psychopathic condition of the gang’s members. It appeared they were using a black taxi to pick up their victims – innocent people on their way home – before kidnapping and murdering them. But they were also killing Protestants too; people who’d fallen foul of their notorious leader, Lenny Murphy. In short, they enjoyed killing for killing’s sake, and in mid-1970s Northern Ireland the opportunity to destroy lives at random, for any scrap of a reason, was unprecedented and easy. Life was cheap and victims would be forgotten about by the next day as another victim took their place.

The politics of Loyalist feuding was way over my head back then, but like everyone else I came to regard the Butchers as nothing short of bogeymen. They invaded my dreams and seemed to be pursuing me during my waking hours. On late summer nights and into the dark nights of autumn 1976, a group of us would gather at the bottom of the estate, playing around the woods and streams that gave this area a kind of weird beauty in the midst of all the mayhem. When darkness fell and it was time to go home, I would walk alone back up the estate, listening out in mortal fear for the distinctive sound of a wailing diesel engine climbing the hill behind me that could only be a Belfast black taxi. I was only just ten by then , but I had no reason to believe the Butchers wouldn’t grab me and rip me apart with their specially sharpened knives, just for the fun of it.

These guys meant business. The body Wee Sam and I saw was the first of four that were dumped on Glencairn by the Butchers, along with others murdered in Loyalist feuds. Some months after we came upon the scene in Forthriver Road, we were playing in and around a building site in ‘the Link’, a new part of Glencairn still under construction. Several houses were being created and while we shouldn’t have been there, nobody was stopping us from running wild around the estate and doing what we liked. We’d poked about one particular half-built house and were about to leave when I spotted what appeared to be words written on an unplastered wall.

‘Gi’e us a match, Sam,’ I said, ‘I wanna see what’s written up there.’

Sam produced a box of matches from his jeans pocket and I struck one, holding it close to the wall. The colour drained from my face as I read the words ‘Help me’. They had been written in blood. Dropping the match we legged it out of there and ran all the way home.

I told Dad, but if I expected him to be shocked I was just as surprised when his reaction was indifference. ‘Just leave well, alone, John,’ he said, shaking his head. ‘You’re better off out of it.’

You have been reading extracts from my No.1 bestselling book : A Belfast Child. See blow for more details and how to order.

Who wants… A signed copy of my No.1 best selling book ? Makes a great Xmas gift for book lovers & those interested in the Troubles & the crazy, mad days my generation lived through.

Click here to order : https://tinyurl.com/2p9b958v

UK orders only – if you live outside the UK email me belfastchildis@googlemail.com and Ill send you a link for ordering outside the UK.

=============================================

To order from Amazon : https://tinyurl.com/wzpp5ra

See: Shankill Butchers

- 6 People lost their lives on the 6th January between 1980 – 2001 . read their stories here :6 People lost their lives on the 6th January between 1980 – 2001 6th January – Deaths & Events in Northern Ireland Troubles

- Merry Christmas to all my friends out there XHi folks, Just a shortish blog post to wish you all a wonderful evening and a fantastic Xmas day. Some of you guys have followed me and my story for years now and during recent tragic soul destroying lows to a few joy filled epic highs you have been there to support , comfort and … Continue reading Merry Christmas to all my friends out there X

- A singed copy of my book for Xmas ?Last chance to order before Xmas delivery cut-off period nxt Wednesday . A personally signed copy of my No.1 Best Selling book : A Belfast Child , which may be worth a few quid if my story is made into a movie – watch this space ! UK Orders Free postage for UK orders only … Continue reading A singed copy of my book for Xmas ?

- I need some help folks 😜And Im happy to bribe you with a free giveaway 🎁 Read on for more detail… Ive doing a soft launch of my online shop : https://deadongifts.co.uk/ which I set up with my sister Mags and I need to drive some traffic to the store and start creating an online presence. The shop will be … Continue reading I need some help folks 😜

- Ireland’s Bloody History – Rathlin Island Massacre July 1575The Rathlin Island massacre took place on Rathlin Island, off the coast of Ireland on 26 July 1575, when more than 600 Scots and Irish were killed.