24th April 1993

Bishopsgate Bombing

The Bishopsgate bombing occurred on Saturday 24 April 1993, when the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) detonated an ANFO truck bomb on Bishopsgate, a major thoroughfare in London’s financial district, the City of London. A news photographer was killed in the explosion and 44 people were injured; the damage cost £350 million to repair. As a result of the bombing, which occurred just over a year after the bombing of the nearby Baltic Exchange, a “ring of steel” was implemented to protect the City, and many firms introduced disaster recovery plans in case of further attacks or similar disasters.

Background

In early 1993 the Northern Ireland peace process was at a delicate stage, with attempts to broker an IRA ceasefire ongoing.Gerry Adams of Sinn Féin and John Hume of the Social Democratic and Labour Party had been engaged in private dialogue since 1988, with a view to establishing a broad Irish nationalist coalition. British Prime Minister John Major had refused to openly enter into talks with Sinn Féin until the IRA declared a ceasefire. The risk of an IRA attack on the City of London had increased due to the lack of progress with political talks, resulting in a warning being circulated to all police forces in Britain highlighting intelligence reports of a possible attack, as it was felt the IRA had sufficient personnel, equipment and funds to launch a sustained campaign in England.[1] During the Troubles the IRA had bombed financial targets in London on a number of occasions, most notably on 10 April 1992 when a truck bomb exploded outside the Baltic Exchange on St. Mary Axe. The Baltic Exchange bombing caused £800 million worth of damage (the equivalent of £1,470 million in 2016), £200 million more than the total damage caused by the 10,000 explosions that had occurred during the Troubles in Northern Ireland up to that point.

————————————-

1993 Bishopsgate London bombing – BBC News

————————————-

The bombing

In March 1993 an Iveco tipper truck was stolen in Newcastle-under-Lyme, Staffordshire, and repainted from white to dark blue. A 1 tonne ANFO bomb made by the IRA’s South Armagh Brigade had been smuggled into England, and was placed in the truck disguised underneath a layer of tarmac. At approximately 9 am on 24 April, two volunteers from an IRA active service unit drove the truck containing the bomb onto Bishopsgate.

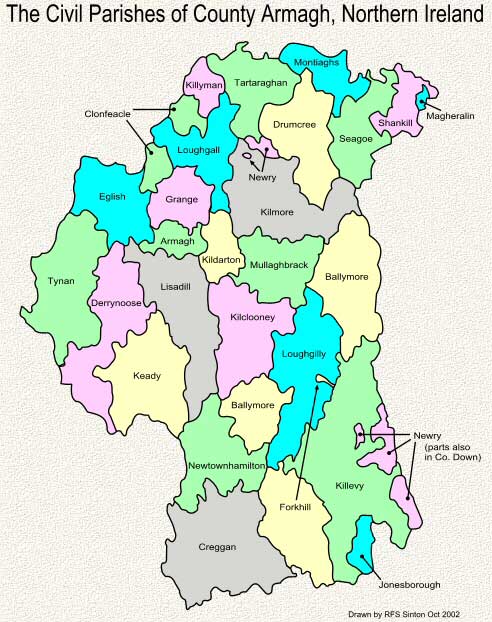

They parked the truck outside 99 Bishopsgate, which was then the Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank, located by the junction with Wormwood Street and Camomile Street, and left the area in a car driven by an accomplice. A series of telephone warnings were then delivered from a phonebox in Forkhill, County Armagh, Northern Ireland, with the caller using a recognised IRA codeword and stating “[there’s] a massive bomb… clear a wide area” Two police officers were already making inquiries into the truck when the warnings were received, and police began evacuating the area.

An Iveco tipper truck, the type used to carry the bomb.

The bomb exploded at 10:27 am causing extensive damage to multiple buildings along a significant stretch of Bishopsgate; the cost of repair was estimated at the time at £1 billion.Buildings up to 500 metres away were damaged, with 1,500,000 sq ft (140,000 m²) of office space being affected and over 500 tonnes of glass broken. The NatWest Tower — at the time the City’s tallest skyscraper – was amongst the structures badly damaged, with many windows on the east side of the tower destroyed; the Daily Mail said “black gaps punched its fifty-two floors like a mouth full of bad teeth” Damage extended as far north as Liverpool Street station and south beyond Threadneedle Street. St Ethelburga’s church, seven metres away from the bomb, collapsed as a result of the explosion. Civilian casualties were low as it was a Saturday morning and the City was typically occupied by only a small number of residents, office workers, security guards, builders, and maintenance staff. Forty-four people were injured by the bomb and News of the World photographer Ed Henty was killed after ignoring police warnings and rushing to the scene.The truck-bomb produced explosive power of 1,200 kg of TNT.

Reaction

The business community and media called for increased security in the City, with one leading City figure calling for “a medieval-style walled enclave to prevent terrorist attacks” Prime Minister John Major received a telephone call from Francis McWilliams, the Lord Mayor of London, reminding him that “the City of London earned £17 billion last year for the nation as a whole. Its operating environment and future must be preserved”. Major, McWilliams and Chancellor of the Exchequer Norman Lamont made public statements that business would continue as normal in the City and that the Bishopsgate bombing would not achieve a lasting effect. Major later gave an account of the public stance taken by his government on the bombing:

Frankly, we thought it was likely to bring the whole process to an end. And we told them repeatedly that that was the case. They assumed that if they bombed and put pressure on the British at Bishopsgate or with some other outrage or other, it would affect our negotiating position to their advantage. In that judgment they were wholly wrong. Every time they did that, they made it harder not easier for any movement to be made towards a settlement. They hardened our attitude, whereas they believed that their actions would soften it. That is a fundamental mistake the IRA have made with successive British governments throughout the last quarter of a century.

John Hume and Gerry Adams issued their first joint statement on the same day as the bombing, stating, “We accept that the Irish people as a whole have a right to national self-determination. This is a view shared by a majority of the people of this island, though not by all its people”, and that, “The exercise of self-determination is a matter for agreement between the people of Ireland”.

The IRA’s reaction appeared in the 29 April edition of An Phoblacht, highlighting how the bombers exploited a security loophole after “having spotted a breach in the usually tight security around the City”. There was also a message from the IRA leadership, calling for

“the British establishment to seize the opportunity and to take the steps needed for ending its futile and costly war in Ireland. We again emphasise that they should pursue the path of peace or resign themselves to the path of war”.

The IRA also attempted to apply indirect pressure to the British government with a statement sent to non-American foreign-owned businesses in the City, warning that “no one should be misled into underestimating the IRA’s intention to mount future planned attacks into the political and financial heart of the British state … In the context of present political realities, further attacks on the City of London and elsewhere are inevitable. This we feel we are bound to convey to you directly, to allow you to make fully informed decisions”.

The City of London Corporation‘s chief planning officer called for the demolition of buildings damaged in the explosion, including the NatWest Tower, seeing an opportunity to rid the City of some of the 1970s architecture and build a new state-of-the-art structure as a “symbol of defiance to the IRA”. His comments were not endorsed by the Corporation themselves, who remarked that the NatWest Tower was an integral part of the City’s skyline.

Aftermath

In May 1993 the City of London Police confirmed a planned security cordon for the City, conceived by its commissioner Owen Kelly, and on 3 July 1993 the ‘ring of steel‘ was introduced.Most routes into the City were closed or made exit-only, and the remaining eight routes into the City had checkpoints manned by armed police CCTV cameras were also introduced to monitor vehicles entering the area, including two cameras at each entry point – one to read the vehicle registration plate and another to monitor the driver and passenger. Over 70 police-controlled cameras monitored the City but to increase coverage of public areas “Camera Watch” was launched in September 1993 to encourage co-operation on surveillance between the police, private companies and the Corporation of London. Nine months after the scheme was launched only 12.5% of buildings had camera systems, but by 1996 well over 1,000 cameras in 376 separate systems were operational in the City.

The bombing resulted in a number of companies changing their working practices and drawing up plans to deal with any future incidents. Documents were blown out of windows of multi-storey buildings by the force of the explosion, prompting the police to use a shredder to destroy all documents found. This resulted in risk managers subsequently demanding a “clear desk” policy at the end of each working day to improve information security.The attack also prompted British and American financial companies to prepare disaster recovery plans in case of future attacks. The World Trade Center bombing in New York City in February 1993 had caused bankruptcy in 40% of the affected companies within two years of the attack, according to a report from analysts IDC. As a result of the Baltic Exchange and Bishopsgate bomb attacks, City-based companies were well-prepared to deal with the aftermath of the September 11 attacks in 2001, with a spokesman for the Corporation of London stating: “After the IRA bombs, firms redoubled their disaster recovery plans and the City recovered remarkably quickly. It has left the City pretty well-prepared for this sort of thing now.”

£350 million for reconstruction

The initial estimate of £1 billion worth of damage was later downgraded, and the total cost of reconstruction was £350 million. The subsequent payouts by insurance companies resulted in them suffering heavy losses causing a crisis in the industry, including the near-collapse of the Lloyd’s of London market. A government-backed insurance scheme, Pool Re, was subsequently introduced in Britain, with the government acting as a “re-insurer of last resort” for losses over £75 million.

The bombing, mounted at a cost of £3,000, was the last major bombing in England during that phase of the Northern Ireland conflict.The campaign of bombing of the UK’s financial centre, described by author and journalist Ed Moloney as “possibly the [IRA’s] most successful military tactic since the start of the Troubles”, was suspended by the IRA to allow the political progress made by Gerry Adams and John Hume to continue. The IRA carried out a number of smaller bomb and mortar attacks in England during the remainder of 1993 and in early 1994, before declaring a “complete cessation of military operations” on 31 August 1994. The ceasefire ended on 9 February 1996 when the IRA killed two people in the Docklands bombing which targeted London’s secondary financial district, Canary Wharf.

Subsequent events

In July 2000 it was announced that Punch magazine was to be prosecuted for contempt of court after publishing an article by former MI5 agent David Shayler. Shayler’s article claimed MI5 could have stopped the Bishopsgate bombing, which a spokesman for Attorney General Lord Williams claimed was a breach of a 1997 court injunction preventing Shayler disclosing information on security or intelligence matters. In November 2000 Punch and its editor were found guilty and fined £20,000 and £5,000 respectively.In March 2001 the editor successfully appealed against his conviction and fine, with an appeal judge accusing the Attorney General of acting like a press censor and ruling that the 1997 injunction was in breach of the European Convention on Human Rights. In December 2002 this decision was overturned at the House of Lords, with five law lords ruling that editor James Steen’s publication of Shayler’s article was indeed in contempt.

On 24 April 2013, a commemorative dinner was held by the Felix Fund, a charity for bomb disposal experts and their families, at the Merchant Taylors’ Hall on Threadneedle Street, to mark 20 years since the Bishopsgate bombing.

Visit the Felix Fund website: www.felixfund.org.uk