The Internal Security Unit

The

IRA’s Nutting Squad

The Internal Security Unit (ISU) was the counter-intelligence and interrogation unit of the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA). This unit was often referred to as the Nutting Squad.

The unit is thought to have had jurisdiction over both Northern and Southern Commands of the IRA, (encompassing the whole of Ireland), and to have been directly attached to IRA General Headquarters (GHQ).

Duties of the ISU

The group was believed to have had a number of briefs:

- Security and character vetting of new recruits to the IRA,

- Collecting and collating material on failed and compromised IRA operations,

- Collecting and collating material on suspect or compromised individuals (informers),

- Interrogation and debriefing of suspects and compromised individuals,

- Carrying out killings and lesser punishments of those judged guilty by IRA courts martial.

The ISU was believed to have unlimited access to the members, apparatus and resources of the IRA in carrying out its duties. Its remit could not be countermanded except by order of the Army Council.

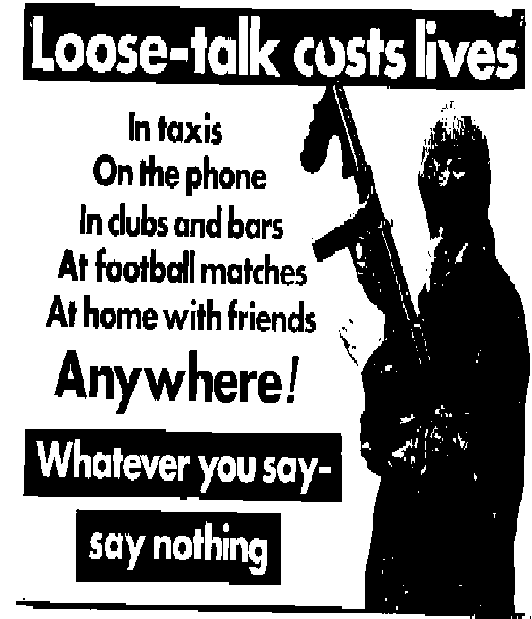

Depositions obtained as part of its operation would ideally be noted on paper, and if possible recorded for the purposes of propaganda.

Examples of ISU activity

- Debriefing of IRA volunteers following their detention by security forces operating in Northern Ireland. These interviews would take place to discover if a volunteer had flipped and decided to betray information or secrets of the organisation. They would also take place in the event of an operation, weapons cache, or unit being exposed to danger or uncovered.

- Involvement in the Court Martial process as detailed in the IRA manual, The Green Book.

See IRA Greenbook

- The membership of the IRA and wider republican community are expected to comply with requests for information made by the ISU, this information then being used to build or demolish accusations made against an IRA volunteer.

Joseph Fenton

Joseph “Joe” Fenton (c. 1953 – 26 February 1989) was an estate agent from Belfast, Northern Ireland, killed by the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) for acting as an informer for RUC Special Branch.

Activity as an informer

In the early 1980s Fenton agreed to help the IRA and moved explosives from an arms dump to a safe house. He was then approached by officers from the Royal Ulster Constabulary‘s Special Branch who said he could be prosecuted for the offence.

The officers said if Fenton agreed to work for them as an informer he would not be prosecuted, and he would be paid in addition. After agreeing to a further meeting with the officers, Fenton tried to extricate himself from the situation by attempting to start a new life in Australia with his wife and four children.

His immigration application was rejected by the Australian High Commission Consulate in Edinburgh, and Fenton started working as an informer for Special Branch in 1982. He started a new job as a salesman for an estate agent, and shortly after started his own estate agency named Ideal Homes based on the Falls Road.

In his role as an estate agent Fenton had access to empty homes that were for sale, which he allowed the IRA to use as safe houses, arms dumps and meeting places for IRA leaders and active service units. Special Branch bugged the houses using covert listening devices, enabling them to gather intelligence. Over twenty IRA members were arrested in possession of firearms, and several IRA bombing units were arrested as they travelled to targets.

A Special Branch officer said of Fenton:

Joe devastated the IRA in west Belfast in the mid-1980s. I was told he loved his work and got a great deal of pleasure after operations were compromised. He was a very willing agent and tried on at least two occasions to entrap senior republicans. But it was probably only a matter of time before he was caught out and by late 1988 he was under suspicion.

Fenton had previously been under suspicion in 1985 following a series of compromised IRA operations. The IRA’s Internal Security Unit (ISU) began an investigation, but Fenton diverted suspicion away from himself by providing the names of two other informers, Gerard and Catherine Mahon who were husband and wife.

The Mahons were interrogated by the ISU and confessed to informing, and were found shot dead in an alleyway in the Turf Lodge area on 8 September 1985. Fenton again came under suspicion in 1988 after four IRA members were arrested at a house in the Andersonstown area of Belfast which was being used as a mortar factory.

Only a few people had knowledge of the location of the factory, and the ISU began a new investigation. As a result of the new investigation the ISU concluded there was a link between compromised IRA operations and homes provided by Fenton. Fenton’s professional life was also investigated, and his sudden ability to start an estate agency business in the early 1980s could not be explained.

Fenton’s handlers in Special Branch stopped paying Fenton when the IRA stopped using properties provided by him, and by the end of 1988 Ideal Homes was facing closure.

By then Fenton was working as a taxi driver to supplement his income, and in early 1989 Ideal Homes ceased trading when the offices were closed by Fenton’s landlord due to unpaid rent.

England

Former Force Research Unit operative Martin Ingram states that Fenton was taken out of Northern Ireland and transported to England by his handlers in Special Branch. Ingram states Fenton wanted to return to Northern Ireland, and asked for help from Andrew Hunter, an MP for the Conservative Party.

Fenton returned to Northern Ireland, with Hunter stating:

“Special Branch told me that if he came home he would be killed very quickly. They warned me he was a marked man and that it was dangerous to be associated with him and I passed this on to him, but he still went back”.

According to Ingram, while back in Belfast Fenton continued to pass information to Special Branch, and in early February 1989 a planned IRA mortar attack was prevented and six IRA members were arrested.

Author and journalist Martin Dillon states Fenton fled to England from Northern Ireland of his own accord, based on an interview with a senior IRA member with access to details of Fenton’s court-martial. Dillon states that Fenton was ordered to return to Northern Ireland by his handlers in Special Branch, and say he had gone to England to see a boxing match. According to the IRA, Special Branch knew Fenton faced execution if he returned and that he was deliberately sacrificed to preoccupy the IRA and divert suspicion from another informer operating within the IRA’s Belfast Brigade.

Death

The IRA abducted Fenton on 24 February 1989, and took him to a house in the Lenadoon area of Belfast. He was interrogated by the ISU and confessed to working as an informer for Special Branch, and was court-martialled.

Fenton was found dead in an alley in Lenadoon on 26 February 1989; he had been shot four times. The following day the IRA issued a statement that Fenton had been killed because he was a “British agent”. In accordance with standard procedure the RUC denied Fenton had any connection with the police, while Fenton’s father Patrick blamed the RUC for his son’s death.

The IRA had shown Fenton’s written confession to his father, and Patrick Fenton stated:

Having seen and read evidence which was presented to me I accept his death and wish to say that the position in which he was placed, due to pressures brought to bear upon him by the Special Branch, led directly to the death of my son.

At Fenton’s funeral the local priest, Father Tom Toner, criticised the role of Special Branch in Fenton’s death stating:

The IRA is not the only secret, death-dealing agent in our midst. Secret agents of the state have a veneer of respectability on its dark deeds which disguises its work of corruption. They work secretly in dark places unseen, seeking little victims like Joe whom they can crush and manipulate for their own purposes. Their actions too corrupt the cause they purport to serve.

Toner was also critical of the IRA’s actions stating:

To you the IRA and all who support you or defend you, we have to say that we feel dirty today. Foul and dirty deeds by Irishmen are making Ireland a foul and dirty place, for it is things done by Irishmen that make us unclean. What the British could never do, what the Unionists could never do, you have done. You have made us bow our heads in shame and that is a dirty feeling.

The IRA is like a cancer in the body of Ireland, spreading death, killing and corruption. It is the unrelenting enemy of life and the community is afraid because it cannot see or identify it. We want the cancer of the IRA removed from our midst but not by means that will leave the moral fibre of society damaged and the system unclean. Fighting evil by corrupt means kills pawns like Joe and leaves every one of us vulnerable and afraid. And it allows Joe’s killers to draw a sickening veneer of respectability over cold-blooded murder and to wash their hands like Pontius Pilate.

Fenton was buried at St Agnes’ Church in Andersonstown, Belfast.

John Joe McGee

John Joe McGee (died 2002, Dundalk, County Louth, Ireland) was an IRA volunteer who was formerly in the British Special Boat Service.

Background

McGee had been a member of the Special Boat Service prior to joining the Irish Republican Army in the 1970s. He was a member of the Provisional IRA‘s ‘nutting squad’ (also known as ‘the unknowns’), the Internal Security Unit. He became its leader for around a decade between the mid-1980s to the mid-1990s. Between forty to fifty of those investigated by the unit were also executed as suspected informers or alleged British agents. Its sentences could only be countermanded by a member of the IRA Army Council. Members of the unit included Eamon Collins, Freddie Scappaticci, and “Kevin Fulton“. During a court appearance, Fulton stated:

“In 1979 I was approached by the Intelligence Corps, a branch of the British Army, whilst serving with my regiment the Royal Irish Rangers in Northern Ireland. I was asked to infiltrate a terrorist group, namely the PIRA during this time as part of my undercover work for the Force Research Unit. I was active in the commission of terrorist acts and crimes … During this time my handlers were fully conversant with my activities and had guided me in my work which included the security section of the PIRA. The commanding officer of this section was John Joe Magee, a former member of the Special Boat Squadron. The purpose of this unit was solely to hunt out agents and informers of the British state. The suspected agents would be … tortured and murdered after obtaining any information.”

Eamon Collins (later killed by the IRA) quoted a conversation he had with McGee and Scappaticci in his book, Killing Rage:

I asked whether they always told people that they were going to be shot. Scap said it depended on the circumstances. He turned to John Joe (his boss, John Joe Magee) and started joking about one informer who had confessed after being offered an amnesty. Scap told the man he would take him home, reassuring him he had nothing to worry about. Scap had told him to keep the blindfold on for security reasons as they walked from the car. “It was funny,” he (Scap) said, “watching the bastard stumbling and falling, asking me as he felt his way along railings and walls, “Is this my house now?” and I’d say, “No, not yet, walk on some more …” ” ‘And then you shot the f—er in the back of the head,” said John Joe, and both of them burst out laughing.”

Eamon Collins

Eamon Collins (1954 – 27 January 1999) was a Provisional Irish Republican Army paramilitary in the late 1970s and early 1980s. He turned his back on the organisation in the late 1980s, and later co-authored a book called Killing Rage detailing his experiences within it. In January 1999 he was waylaid on a public road and murdered near his home in Newry in Ulster.

Early life

Collins, the son of a cattle dealer, grew up in a middle class Irish family in Camlough, a small, staunchly Irish republican town in South Armagh. Despite the sentiment of the area, the Collins family had no association and little interest in Irish Nationalist politics. Collins’ mother was devout Catholic, and he was brought up under her influence with a sense of awe for the martyrs of that religion in Irish history, in its conflicts with Protestantism.

After completing his schooling, Collins worked for a time in the Ministry of Defence in a clerical capacity in London before studying Law at Queen’s University, where he became influenced by Marxist political ideology.

In Easter 1974, as he walked home to his parents’ home in South Armagh during a break from his studies in Belfast, on arrival he found both his parents being man-handled by British troops during a house-to-house raid searching for illegal weapons, and on remonstrating with them Collins was himself seriously assaulted, and both he and his father were arrested and detained.

Collins later attributed his crossing of the psychological threshold of actively supporting anti-British Irish paramilitarist terrorism to this incident. Another influence upon his radicalization at this time was a Law tutor at university who had persuaded him that the newly formed Provisional Irish Republican Army was, as well as a means opposing the British military presence in Ulster, a vehicle for Marxist revolutionary politics, in line with the radical ideological expression of a younger generation in the late 1960’s – early 1970’s that were now replacing an old guard of a movement that had engaged in little more than petty acts of Fenian paramilitary activity in the 1950’s-1960’s.

Collins subsequently dropped out of university, and after working in a pub for a period, he joined Her Majesty’s Customs & Excise Service, serving in Newry, and would go on to use this internal position within the administrative machinery of the British Government to support IRA operations against Crown Forces personnel.

Around this time he married Bernadette, with whom he subsequently had four children.

IRA career

Collins joined the Provisional IRA during the blanket protest by Long Kesh inmates in the late 1970s, which sought Special Category Status for republican prisoners, and he became involved in street demonstrations at this time. He joined the “South Down Brigade” of the IRA, based around Newry. This was not one of the organisation’s most active formations, but it sometimes worked alongside the “South Armagh Brigade“, which was one of its most aggressive units.

Psychologically unsuited to physical violence, Collins was appointed instead by the IRA as its South Down Brigade’s intelligence officer. This role involved gathering information on members of the Crown security forces personnel and installations for targeting in gun and bomb attacks. His planning was directly responsible for at least five murders, including that of the Ulster Defence Regiment Maj. Ivan Toombs in January 1981, with whom Collins worked in the Customs Station at Warrenpoint, and possibly three times that number.

Many of the bombing targets of his unit were of limited significance, such as the destruction of Newry public library, and a public house where a Royal Ulster Constabulary choir drank after practice.

Collins became noted within IRA circles for his hard-line views on the continuance of armed campaign, and later joined its Internal Security Unit. At the instigation of the South Armagh Brigade’s leadership he became a member of Sinn Féin in Newry. The South Armagh IRA wanted a hard-line militarist in the local party, as they were opposed to the increasing emphasis of the republican leadership on political over military activity.

Collins was not selected as a Sinn Féin candidate for local government elections, in part, due to his open expressions of suspicion of the IRA and Sinn Féin leadership, whom he accused of covertly moving towards a position of an abandonment of the IRA’s military campaign. Around this time Collins had a confrontation with Gerry Adams at the funeral of an IRA man killed in a failed bombing over how to deal with the funeral’s policing, where Collins accused Adams a being a “Stick” (a derogatory slang term among IRA supporters for activists among it who were considered lacking sincerity in their commitment to its cause).

Despite his militarist convictions at this time Collins found the psychological strain caused by his involvement in the terrorist war increasingly difficult to deal with. His belief in the martial discipline of IRA’s campaign had been seriously undermined by the event of the assassination of Norman Hanna, a 28 year old Newry man on the 11 March 1982 in front of his wife and young daughter, who had been targeted because of his former service with the Ulster Defence Regiment, which he had resigned from in 1976. Collins had opposed the targeting of Hanna on the basis that it wasn’t of a governmental entity, but had been over-ruled by his superiors, and he had gone along with the operation; his conscience burdened him afterwards about it though.

His uneasy state was further augmented by being arrested under anti-terrorism laws on two occasions, the second involving his detention at Gough Barracks in Armagh for a week, where he was subject to extensive sessions of interrogation in 1985 after an IRA mortar attack in Newry, which had claimed the lives of multiple police officers. Collins had not been involved in this operation, but after five days of incessant psychological pressure being exerted by R.U.C. specialist police officers, during which he had not said a word, he mentally broke, and yielded detailed information to the police about the organization.

As a result of his arrest he was dismissed from his career with H.M. Customs & Excise Service.

Collins subsequently stated that the strain of the interrogation merely exacerbated increasing doubts that he had already possessed about the moral justification of the IRA’s terrorist paramilitary campaign and his actions within it. These doubts had been made worse by the strategic view that he had come to that the organization’s senior leadership had in the early 1980’s quietly decided that the war had failed, and was now slowly manoeuvering the movement away from a military campaign to allow its political wing Sinn Féin to pursue its purposes by another means in what would become the Northern Ireland peace process.

This negated in Collins’ mind the justification for its then on-going military actions.

Statements against the IRA

After his confession of involvement in IRA activity, Collins became an IRA – in contemporary media language – “Supergrass“, upon whose evidence the authorities were able prosecute a large number of IRA members. Subsequently he was incarcerated in specialized protective custody with other paramilitaries who had after arrest given evidence against their organizations in the Crumlin Road Prison in Belfast from 1985 to 1987.

However, after an appeal from his wife who remained an IRA supporter, and on receiving a message from the IRA delivered by his brother on a visit to the prison, Collins legally retracted his evidence, in return for which he was given a guarantee of safety by the IRA, provided he consented to being debriefed by it. He agreed, and was in consequence transferred by the authorities to the Irish paramilitary wing of the prison.

Trial for murder

As a result of losing his previous legal status as a Crown protected witness, Collins was charged with several counts of murder and attempted murder. However, on being tried in 1987 he was acquitted as the statement in which he had admitted to involvement in these acts was ruled legally inadmissible by the court, as it was judged that it had been obtained under duress and was not supported by enough conclusive corroboratory evidence to allow a legally sound conviction.

On release from prison he spent several weeks being counter-interrogated by the IRA’s Internal Security Unit to discover what had been revealed to the authorities, after which he was exiled by the organization from Ulster, being warned that if he was found north of Drogheda after a certain date he would be executed by it. The technical acquittal in the Crown court based upon judicial legal principles made an impact upon Collins’ view of the British state, markedly contrasting with what he had witnessed in the IRA’s Internal Security Unit, and reinforced his disillusionment with Irish paramilitarism.

Post-IRA life

After his exile Collins moved to Dublin and squatted for a while in a deserted flat in the impoverished Ballymun area of the city. At the time the area was experiencing an epidemic of heroin addiction and he volunteered to help a local priest Peter McVerry, who ran programmes for local youths to try to keep them away from drugs. After several years in Dublin, he subsequently moved to Edinburgh, Scotland for a period, where he ran a youth centre. He would later write that because of his Ulster background he felt closer culturally to Scottish people than people from the Irish Republic.

In 1995 he returned to live in Newry, a district known for the militancy of its communal support of the IRA, with numerous IRA members in its midst. The IRA order exiling him from Ulster had not been lifted, but with a formal ceasefire from the organization in operation ordered by its senior command, and in the sweeping changes that were underway with renunciations of violence by all the paramilitary organizations in the province that had followed on from it, he judged it safer to move back in with his wife and children who had never left the town.

Broadcasting and published works

Having returned to live in Newry, rather than maintaining a low profile Collins decided to take a prominent role in the ongoing transition of Ulster’s post-war society, using his personal history as a platform in the media to analyze the adverse effects of terrorism. In 1995 he appeared in an ITV television documentary entitled ‘Confession’ giving an account of his disillusioning experiences and a bleak insight into Irish paramilitarism.

In 1997 he co-authored Killing Rage, with journalist Mick McGovern, a biographical account of his life and IRA career. He also contributed to the book Bandit Country by Toby Harnden about the South Armagh IRA. At the same time in the media he called for the re-introduction of Internment after the Omagh bombing for those continuing to engage in such acts; published newspaper articles openly denouncing and ridiculing the fringe Real IRA’s attempts to re-ignite paramilitary warfare in Ulster, alongside publicly analyzing his own past role in such activity, and the damage that it had caused on a personal and social level to the two communities of Ulster.

Witness evidence against Thomas Murphy

In May 1998 Collins gave evidence against leading republican Thomas “Slab” Murphy, in a libel case Murphy had brought against the Sunday Times, over a 1985 article naming him as the IRA’s Northern Commander.

Murphy denied IRA membership, but Collins took the witness stand against him, and testified that from personal experience he knew that Murphy had been a key military leader in the organization. Murphy subsequently lost the libel case and sustained substantial financial losses in consequence.

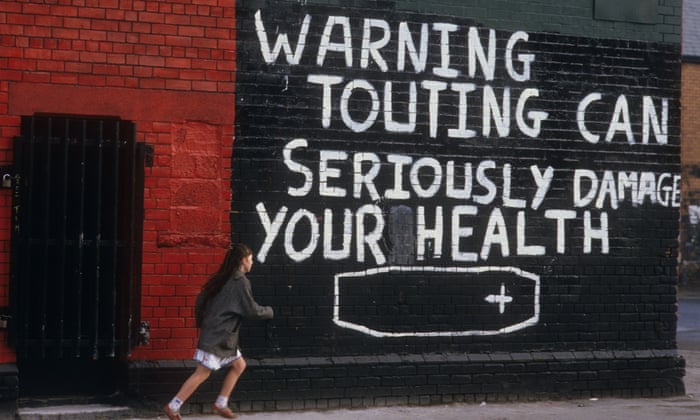

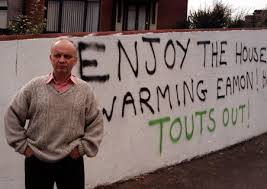

After giving his testimony Collins had said in the court-room to Murphy “No hard feelings Slab”. However, soon after the trial Collins’ home was attacked and daubed with graffiti calling him a “tout”, a slang word for an informer. Since his return to Newry in 1995 his home there had been intermittently attacked with acts of petty vandalism, but after the Murphy trial these intensified in regularity and severity, and another house belonging to his family in Camlough, in which no one was resident, was destroyed by arson. Threats were made against his children, and they faced persecution in school from elements among their peers. Graffiti threatening him with murder was also daubed on the walls of the streets in the vicinity of the family home in Newry.

Death

Collins was beaten and stabbed to death in his 45th year by an unidentified assailant(s) early in the morning of 27 January 1999, whilst walking his dogs near the Barcroft Park Estate in Newry along a quiet stretch of country lane at Doran’s Hill, just within sight of Sliabh gCuircin (Camlough Mountain). His body also bore marks of having been struck by a car moving at speed. The subsequent police investigation and Coroner’s Inquest commented upon the extremity of weaponed violence to Collins’ head and face used during the attack.

Rumoured reasons behind the murder were that he had returned to Ulster in breach of the IRA’s banning order, and further he had detailed IRA activities and publicly criticized in the media a multiplicity of Irish terrorist paramilitary splinter groups that had appeared after the IRA’s 1994 ceasefire, and that he had testified in court against Murphy.

Gerry Adams stated the murder was “regrettable”, but added that Collins had “many enemies in many places”.

After a traditional Irish wake, with a closed coffin necessitated due to the damage to his face, and a funeral service at St. Catherine’s Church in Newry, Collins’ body was buried at the town’s Monkshill Cemetery, not far from the grave of Albert White, a Catholic former Royal Ulster Constabulary Inspector, whose assassination he helped to organize in 1982.

Subsequent criminal investigations

In January 2014 the Police Service of Northern Ireland released a statement that a re-examination of the evidence from the scene of the 1999 murder had revealed new DNA material of a potential perpetrator’s presence, and made a public appeal for information, detailing the involvement of a specific car model (a white coloured Hyundai Pony), and a compass pommel that had broken off of a hunting knife during the attack and had been left behind at the scene.

In February 2014 detectives from the Serious Crime Branch arrested a 59 year old man at an address in Newry in relation to the murder, he was subsequently released without charge. In September 2014 the police arrested three men, aged 56, 55 and 42 in County Armagh in relation to inquiries into the murder, all of whom were subsequently released without charges after questioning

Murders of Catherine and Gerard Mahon

Catherine and Gerard Mahon were a husband and wife who lived with their children in Twinbrook, Belfast. Gerard, aged twenty-eight, was a mechanic; Catherine, was twenty-seven. They were killed by the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) on 8 September 1985, the IRA alleging they were informers. However at least two of those responsible for their deaths were later uncovered as British agents within the IRA’s Internal Security Unit, leaving the actual status of the Mahons as informers open to doubt.

Background

The Mahons were neighbours of estate agent Joseph Fenton, a supplier of ‘safe houses’ for the IRA, but also a British agent. When a number of IRA missions were compromised, Fenton is believed to have directed a member of the Internal Security Unit, Freddie Scappaticci, and three other men, to the Mahons.

Abducted in August, interrogated and beaten for prolonged periods, the Mahons eventually confessed that their flat was bugged by the Royal Ulster Constabulary, who are alleged to have paid the couple for information, weapons finds, or arrests. The IRA took the couple to Norglen Crescent in Turf Lodge and shot them.

It is thought Catherine Mahon was shot in the back while trying to escape.

Those who found their bodies said at the time:

We heard two bursts of gunfire and then a car was driven away at high speed. We went out and discovered the girl. We thought she was dead. We tried first aid but the side of her head was blown away. A young lad came up to us saying there was a man lying in the entry a bit further up and still alive. We got to him and he was badly wounded. He was struggling to breath and choking on his own blood. He had been hit in the side of the head and the face. Whatever is behind it all, it’s ridiculous. Those responsible are animals. Nothing justifies murder. They had both been tied by their wrists – but they must have broken free by struggling when they realised what was going to happen.

Dr Joe Hendron of the Social Democratic and Labour Party released a statement, remarking:

This slaughter has few equals in barbarity and it proves the Provo idea of justice is warped. It makes us all sick.

Victims were ‘sacrificed’ by agent known as Stakeknife

SOME of the killings to be investigated as part of the new probe into the activities of the agent known as Stakeknife and those in the intelligence services who directed him:

* Husband and wife Gerard (28) and Catherine (27) Mahon, who were shot dead after being taken away from their Twinbrook home in west Belfast in September 1985 and interrogated by the IRA who claimed they were informers. The Mahons were neighbours of estate agent Joe Fenton, who was also later killed by the IRA. When a number of IRA missions were compromised, Fenton is believed to have directed a member of the IRA’s internal security unit to the Mahons

* Frank Hegarty. The body of the 45-year-old was discovered in Co Tyrone close to the border in May 1986. He had been shot dead and his eyes were taped shut. From the Shantallow area of Derry, the IRA alleged he was an informer who had revealed the location of an arms dump in Sligo to authorities

* Joseph Fenton. The 35-year-old, who worked as an estate agent, was shot in the head by the IRA in February 1989 after he was accused of working as an informer. It was alleged the father-of-four from west Belfast man was providing ‘safe houses’ for IRA planning meetings that were then bugged by the security forces

* Joseph Mulhern. The 22-year-old’s body was discovered close to the Tyrone border 10 days after he disappeared from west Belfast in 1993. The IRA alleged he was working for RUC Special Branch

* Caroline Moreland. The 34-year-old mother-of-three was abducted from her home in the Beechmount area of west Belfast in July 1994. Her body was discovered dumped on the Fermanagh border 10 days after she disappeared. Her family had been warned by the IRA not to report her missing

* Margaret Perry (26) disappeared from her hone of Portadown in July 1991, with her body found in shallow grave at Mullaghmore, Co Donegal in June 1992. The IRA claimed she was killed by three men acting on behalf of British intelligence because she had discovered her former boyfriend Gregory Burns (34) was informing to the security forces. He, along with Johnny Dingham (32) and Adrian Starrs (29), were abducted, tortured and shot dead by the IRA

* Charlie McIlmurray (32), from Slemish Way in Andersonstown, was shot by the IRA in April 1987 following allegations that he had been working as an informer. His body was discovered in a van at Killeen in Co Armagh on the border

* Peter Valente (33), a father of four, was killed as an alleged informer in November 1980. Unusually, his body was dumped in the loyalist Highfield estate and a statement was released by Sinn Féin blaming the UDA. However, it is now thought that along with a number of other victims he was targeted by Stakeknife to protect his own cover as an agent after the IRA became suspicious

* Vincent Robinson (29) from Andersonstown in west Belfast was found dead in a rubbish chute in the Divis flats complex in June 1981. The IRA claimed he was an informer and had been outed by Peter Valente, something that his family denied. Again it is believed he was ‘sacrificed’ in order to protect Stakeknife

* Maurice Gilvarry (24) from Ardoyne in north Belfast was shot dead in January 1981 and his body dumped in south Armagh. Again it was alleged he was implicated by Peter Valente but it is now thought he was killed to protect the identity of Stakeknife

* Patrick Trainor (28). Married with three children, his body was found at waste ground near the Glen Road in west Belfast after he had been abducted by the IRA who alleged he was an informer, based on information they claimed came from Peter Valente. This was denied by his family and an RUC detective at a subsequent inquest.

See Stakeknife

See The Disappeared

- 6 People lost their lives on the 6th January between 1980 – 2001 . read their stories here :6 People lost their lives on the 6th January between 1980 – 2001 6th January – Deaths & Events in Northern Ireland Troubles

- Merry Christmas to all my friends out there X

Hi folks, Just a shortish blog post to wish you all a wonderful evening and a fantastic Xmas day. Some of you guys have followed me and my story for years now and during recent tragic soul destroying lows to a few joy filled epic highs you have been there to support , comfort and … Continue reading Merry Christmas to all my friends out there X

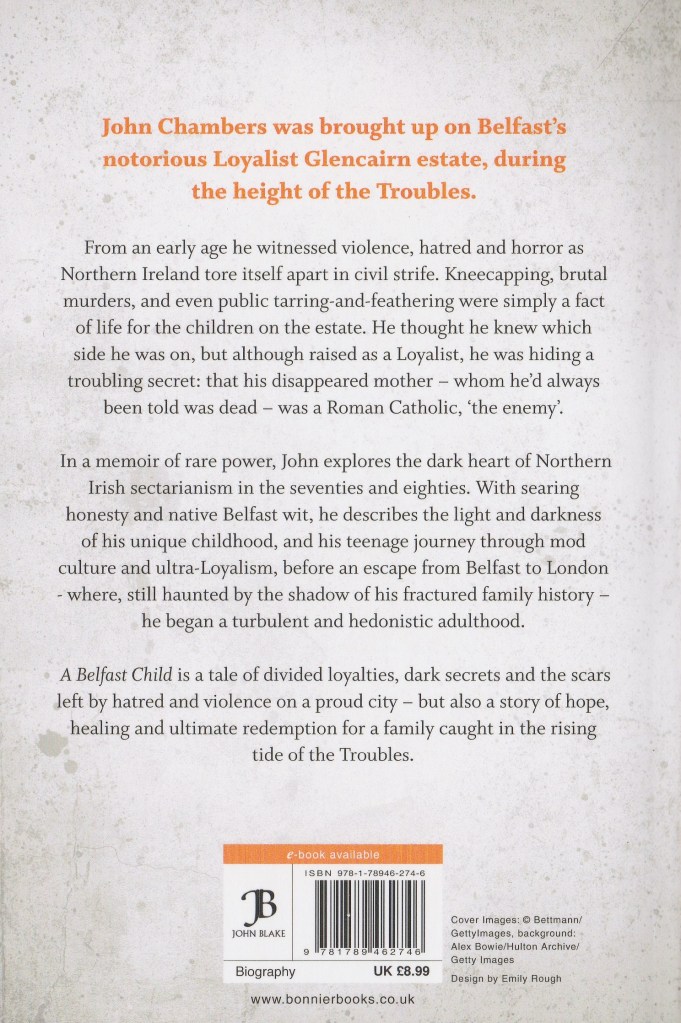

Hi folks, Just a shortish blog post to wish you all a wonderful evening and a fantastic Xmas day. Some of you guys have followed me and my story for years now and during recent tragic soul destroying lows to a few joy filled epic highs you have been there to support , comfort and … Continue reading Merry Christmas to all my friends out there X - A singed copy of my book for Xmas ?

Last chance to order before Xmas delivery cut-off period nxt Wednesday . A personally signed copy of my No.1 Best Selling book : A Belfast Child , which may be worth a few quid if my story is made into a movie – watch this space ! UK Orders Free postage for UK orders only … Continue reading A singed copy of my book for Xmas ?

Last chance to order before Xmas delivery cut-off period nxt Wednesday . A personally signed copy of my No.1 Best Selling book : A Belfast Child , which may be worth a few quid if my story is made into a movie – watch this space ! UK Orders Free postage for UK orders only … Continue reading A singed copy of my book for Xmas ? - I need some help folks 😜

And Im happy to bribe you with a free giveaway 🎁 Read on for more detail… Ive doing a soft launch of my online shop : https://deadongifts.co.uk/ which I set up with my sister Mags and I need to drive some traffic to the store and start creating an online presence. The shop will be … Continue reading I need some help folks 😜

And Im happy to bribe you with a free giveaway 🎁 Read on for more detail… Ive doing a soft launch of my online shop : https://deadongifts.co.uk/ which I set up with my sister Mags and I need to drive some traffic to the store and start creating an online presence. The shop will be … Continue reading I need some help folks 😜 - Ireland’s Bloody History – Rathlin Island Massacre July 1575

The Rathlin Island massacre took place on Rathlin Island, off the coast of Ireland on 26 July 1575, when more than 600 Scots and Irish were killed.

The Rathlin Island massacre took place on Rathlin Island, off the coast of Ireland on 26 July 1575, when more than 600 Scots and Irish were killed.