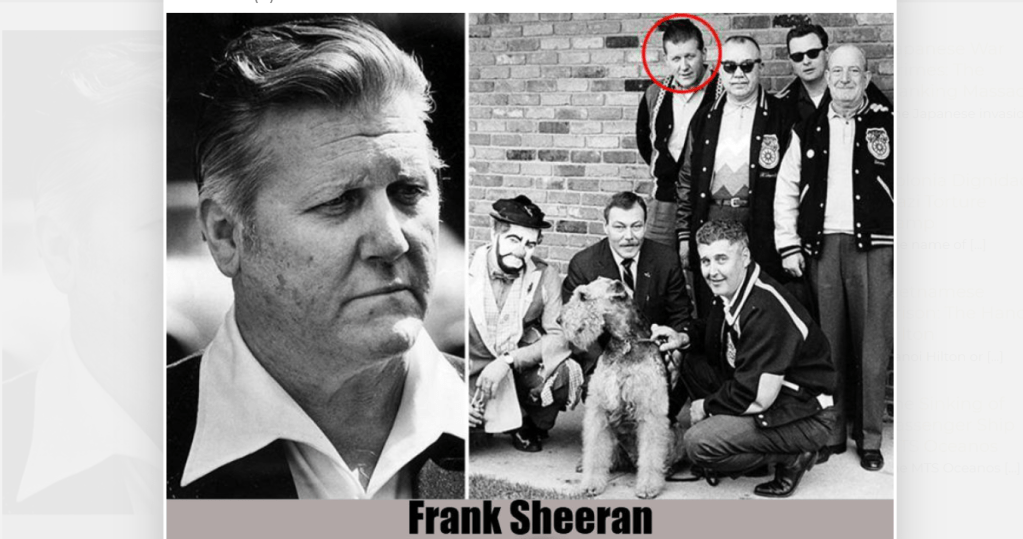

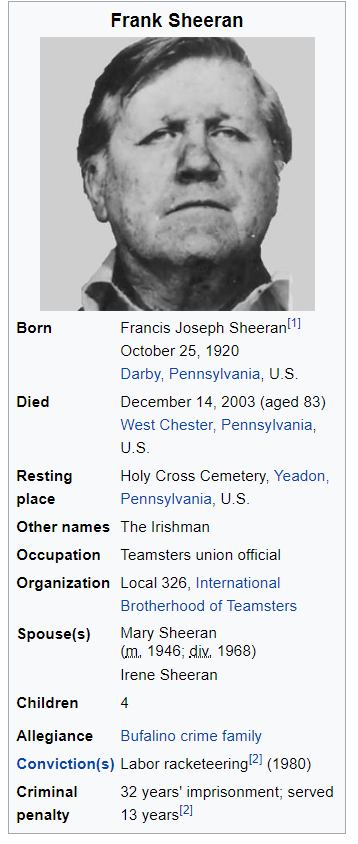

Frank Sheeran

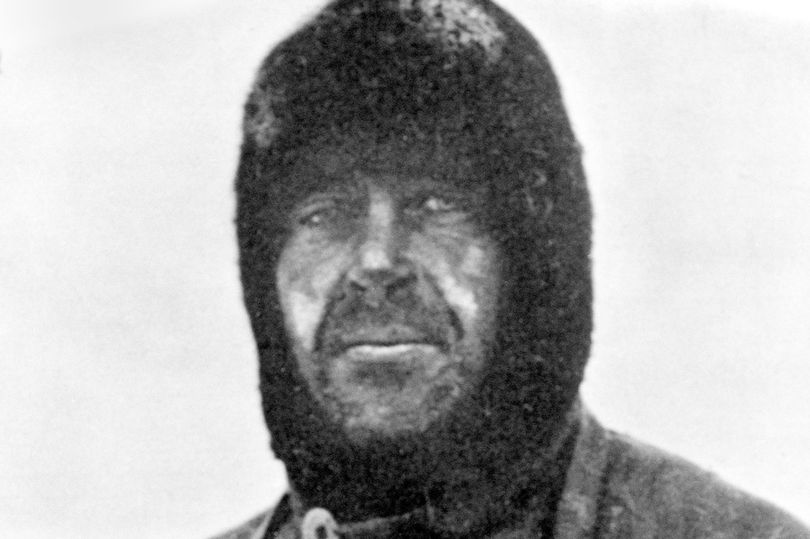

The (real) Irish Man , life & death

Francis Joseph Sheeran (October 25, 1920 – December 14, 2003), known as Frank “the Irishman” Sheeran, was an American labor union official who was accused of having links to the Bufalino crime family in his capacity as a high-ranking official in the International Brotherhood of Teamsters (IBT), the president of Local 326.

Sheeran was a leading figure in the corruption of unions by organized crime. In 1980, he was convicted of labor racketeering and sentenced to 32 years in prison, of which he served 13 years. Shortly before his death, he claimed to have killed Teamster leader Jimmy Hoffa in 1975. Author Charles Brandt detailed what Sheeran told him about Hoffa in the narrative nonfiction work I Heard You Paint Houses (2004).

The truthfulness of the book has been disputed by some, including Sheeran’s confessions to killing Hoffa and Joe Gallo. The book is the basis for the 2019 film The Irishman directed by Martin Scorsese and starring Robert De Niro as Frank Sheeran and Al Pacino as Hoffa.

The Irishman Explained | The Reel Story

My thoughts:

Well I watched The Irish Man yesterday evening, all three and a half of it and to be completely honest I thought it was a load of rubbish and a waste of three and a half hours of my life i’ll never get back. Its not a patch on Goodfellas or The God Father and the constant flash backs to when the main players were younger was to say the least completely off putting and unbelievable in the extreme. They looked and moved like the elder actors they are and it was painful watching these icons of gangsters movies having to shame themselves in this manner. Plus, the story line and the dialogue were abysmal and so far removed from the true events that reality had to be suspended and I had to force myself to sit through the whole sorry mess until the bitter , disappointing end.

Early life

Sheeran was born and raised in Darby, Pennsylvania, a small working-class borough on the outskirts of Philadelphia. He was the son of Thomas Francis Sheeran Jr. and Mary Agnes Hanson. His father was of Irish descent, while his mother was of Swedish descent.

World War II

Sheeran enlisted in the Army in August 1941, did his basic training near Biloxi, Mississippi, and was assigned to the military police. Following the attack on Pearl Harbor, he volunteered for training in the Army Airborne at Fort Benning, Georgia, but he dislocated his shoulder and was transferred to the 45th Infantry Division, known as “The Thunderbirds” and “The Killer Division”. On July 14, 1943, he set sail for North Africa.

Sheeran served 411 days of combat duty—a significant length of time, as the average was around 100 days. His first experience of combat was during the Italian Campaign, including the invasion of Sicily, the Salerno landings, and the Anzio Campaign. He then served in the landings in southern France[11] and the invasion of Germany.

Sheeran said:

All in all, I had fifty days lost under AWOL—absent without official leave—mostly spent drinking red wine and chasing Italian, French, and German women. However, I was never AWOL when my outfit was going back to the front lines. If you were AWOL when your unit was going back into combat you might as well keep going because one of your own officers would blow you away and they didn’t even have to say it was the Germans. That’s desertion in the face of the enemy.

War crimes

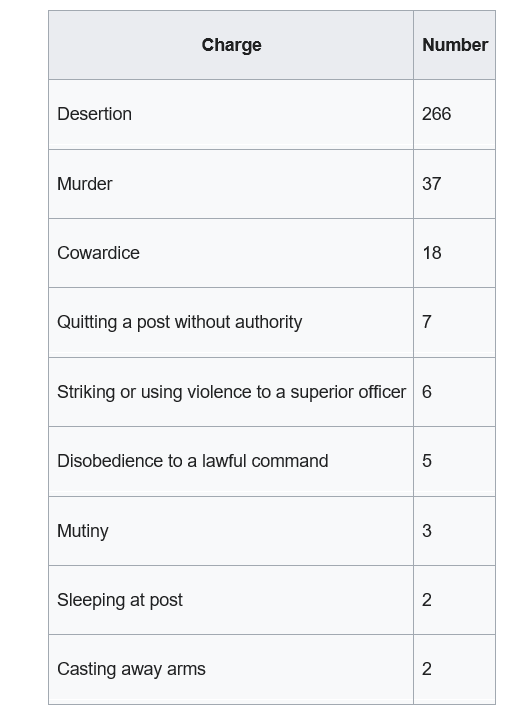

Sheeran recalled his war service as the time when he developed a callousness to taking human life. He claimed to have participated in numerous massacres and summary executions of German POWs, acts which violated the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907 and the 1929 Geneva Convention on POWs. In interviews with Charles Brandt, he divided such massacres into four categories:

- Revenge killings in the heat of battle. Sheeran told Brandt that a German soldier had just killed his close friends and then tried to surrender, but he chose to “send him to hell, too”. He described often witnessing similar behavior by fellow GIs.

- Orders from unit commanders during a mission. Sheeran described his first murder for organized crime: “It was just like when an officer would tell you to take a couple of German prisoners back behind the line and for you to ‘hurry back’. You did what you had to do.”

- The Dachau reprisals and other reprisal killings of concentration camp guards and trustee inmates.

- Calculated attempts to dehumanize and degrade German POWs. Sheeran’s unit was climbing the Harz Mountains when they came upon a Wehrmacht mule train carrying food and drink up the mountainside. The female cooks were allowed to leave unmolested, then Sheeran and his fellow GI’s “ate what we wanted and soiled the rest with our waste”. Then the Wehrmacht mule drivers were given shovels and ordered to “dig their own shallow graves”. Sheeran joked that they did so without complaint, likely hoping that he and his buddies would change their minds. But the mule drivers were shot and buried in the holes they had dug. Sheeran explained that by then, he “had no hesitation in doing what I had to do.”

Discharge and post-war

Sheeran was discharged from the army on October 24, 1945. He later recalled that it was “a day before my twenty-fifth birthday, but only according to the calendar.” Upon returning from his army service, Sheeran married Mary Leddy, an Irish immigrant. The couple had three daughters, MaryAnne, Dolores, and Peggy, but divorced in 1968. Sheeran then married Irene Gray, with whom he had one daughter, Connie.

Organized crime and the Teamsters Union

When he left the service, Sheeran became a meat driver for Food Fair, and he met Russell Bufalino in 1955 when Bufalino offered to help him fix his truck, and later worked jobs driving him around and making deliveries. Sheeran also operated out of a bar located in Sharon Hill, Pennsylvania which was run by Bill Distanisloa, a soldier for Angelo Bruno.

Sheeran’s first murder was killing Whispers DiTullio, a gangster who had hired him to destroy the Cadillac Linen Service in Delaware for $10,000. Sheeran did not know, however, that Angelo Bruno had a large stake in the linen service. Sheeran was spotted outside the business in Delaware and was brought in for questioning. Bufalino had convinced Bruno to spare Sheeran, but he ordered Sheeran to kill DiTullio as retribution.

Sheeran was also suspected of the murder of Joe Gallo at Umberto’s Clam House on April 7, 1972.

Bufalino introduced Sheeran to Teamsters International President Jimmy Hoffa. Hoffa became a close friend and used Sheeran for muscle, including the assassination of recalcitrant union members and members of rival unions threatening the Teamsters’ turf. According to Sheeran, the first conversation that he had with Hoffa was over the phone, where Hoffa started by saying, “I heard you paint houses”—a mob code meaning “I heard that you kill people”, the “paint” being spattered blood.

Sheeran later became acting president of Local 326 of the Teamsters Union in Wilmington, Delaware.

Sheeran was charged in 1972 with the 1967 murder of Robert DeGeorge, who was killed in a shootout in front of Local 107 headquarters. The case was dismissed, however, on the grounds that Sheeran had been denied a speedy trial. He was also alleged to have conspired to murder Francis J. Marino in 1976, a Philadelphia labor organizer, and Frederick John Gawronski, killed the same year in a tavern in New Castle, Delaware.

Prison and death

Sheeran was indicted along with six others in July 1980, on charges involving his links to the labor leasing businesses controlled by Eugene Boffa Sr. of Hackensack, New Jersey. On October 31, 1980, Sheeran was found guilty of 11 charges of labor racketeering. He was sentenced to a 32-year prison term and served 13 years.

Sheeran died of cancer on December 14, 2003, aged 83, in a nursing home in West Chester, Pennsylvania. He was buried at Holy Cross Cemetery in Yeadon, Pennsylvania.

Hoffa death

The Sinister Disappearance of Jimmy Hoffa

Charles Brandt claims in I Heard You Paint Houses (2004) that Sheeran confessed to killing Hoffa. According to Brandt’s account, Chuckie O’Brien drove Sheeran, Hoffa, and fellow mobster Sal Briguglio to a house in Metro Detroit. O’Brien and Briguglio drove off and Sheeran and Hoffa went into the house, where Sheeran claims that he shot Hoffa twice in the back of the head. Sheeran says that he was told that Hoffa was cremated after the murder. Sheeran also confessed to reporters that he murdered Hoffa.

Bill Tonelli disputes the book’s truthfulness in his Slate article “The Lies of the Irishman”, as does Harvard Law School professor Jack Goldsmith in “Jimmy Hoffa and ‘The Irishman’: A True Crime Story?” which appeared in The New York Review of Books.

Blood stains were found in the Detroit house where Sheeran claimed that the murder happened, but they were determined not to match Hoffa’s DNA. The FBI continues its attempts to connect Sheeran to the murder, retesting the blood and floorboards with latest advancements in forensics.

Biographical film

The book is the basis for the 2019 film The Irishman directed by Martin Scorsese. Scorsese was long interested in directing a film about Sheeran’s life and his alleged involvement in the slaying of Hoffa. Steven Zaillian is the screenwriter and co-producer Robert De Niro portrays Sheeran, with Al Pacino as Hoffa, and Joe Pesci as Bufalino.[The film had its world premiere at the New York Film Festival on September 27, 2019, and was released on November 1, 2019, with digital streaming that started on November 27, 2019, via Netflix.

Main Source : Wikipedia Frank Sheeran

“The Irishman” Official Documentary

Other gangster posts

- 6 People lost their lives on the 6th January between 1980 – 2001 . read their stories here :

6 People lost their lives on the 6th January between 1980 – 2001

6th January – Deaths & Events in Northern Ireland Troubles - Merry Christmas to all my friends out there X

Hi folks,

Just a shortish blog post to wish you all a wonderful evening and a fantastic Xmas day.

Some of you guys have followed me and my story for years now and during recent tragic soul destroying lows to a few joy filled epic highs you have been there to support , comfort and celebrate with me whatever a pernicious fate throws in my path and I am truly grateful.

This year I’ve invited all the family to my place for Xmas dinner and tbh it’s been a logistical (expensive) nightmare trying to accommodate and please everyone. Mother-in-law is a pure traditionalist and in what I suspected was a threatening tone kept informing me she is really looking forward to her turkey dinner with all the trimmings.

Simone, the kids and myself aren’t particularly fond of turkey and have been debating among ourselves whether we should just buy a giant chicken and hope mother-in-law wouldn’t notice. Obviously, there’s a tout among us and my monies on Simone or Autumn telling mother-in-law of the conspiracy to fool her with a giant chicken.

So, turkey is back on the menu !

We discussed what everyone else preferred for mains and of course that wasn’t plain sailing either. Autumn wanted gammon, I wanted lamb , Simone wasn’t fussed and Jude demanded chicken because he hates turkey and it would ruin his day if he didn’t have a turkey substitute on his Xmas plate. I helpfully suggested we held a democratic vote to decide which meats to go for and to my shock and surprise they all decided I wasn’t part of their democratic voting circle and I was out of the equation. Brutal. By this stage I’d had enough, and I threw the towel in and ended up buying everything, including a small chicken.

For starters we’re having tiger prawns , pate & rustic rolls and salmon with pomegranate glaze , something we al agreed to to keep everyone happy – phew.

Anyways Jude and autumn are helping with Xmas dinner and despite all the stress I’m looking forward to spending some quality time with them all and after dinner we’ll play some games and watch a little telly.

Perfect!

Ill finish by wishing you and all those you love and cherish a safe and wonderful time this Xmas and may Santa bring you all you hope for.

God bless you all as we celebrate the birth of Jesus Christ

Merry Xmas everyone X

Laters X

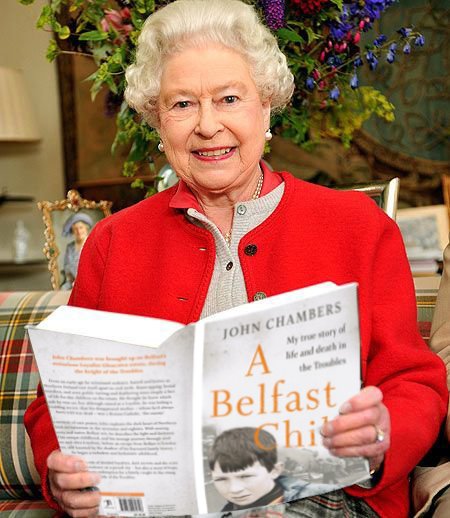

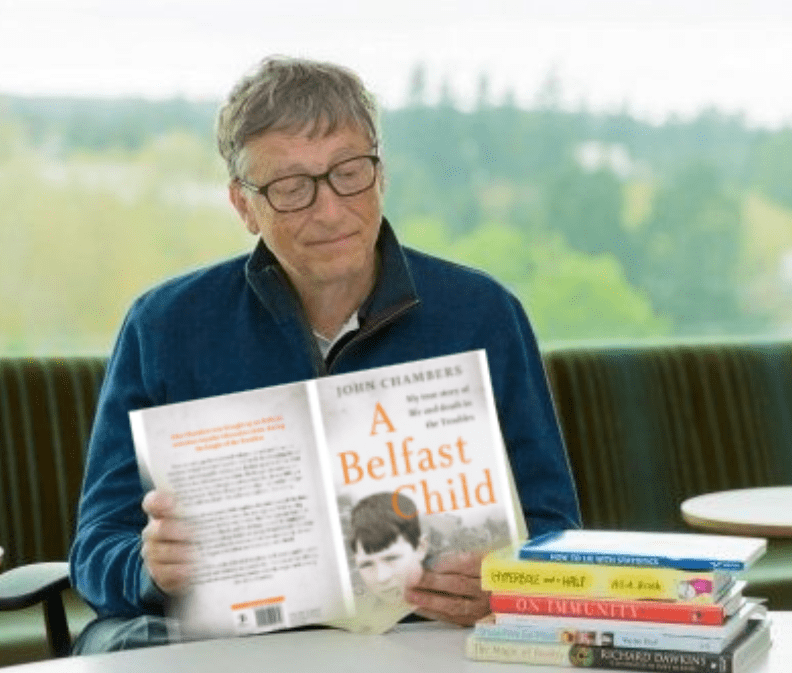

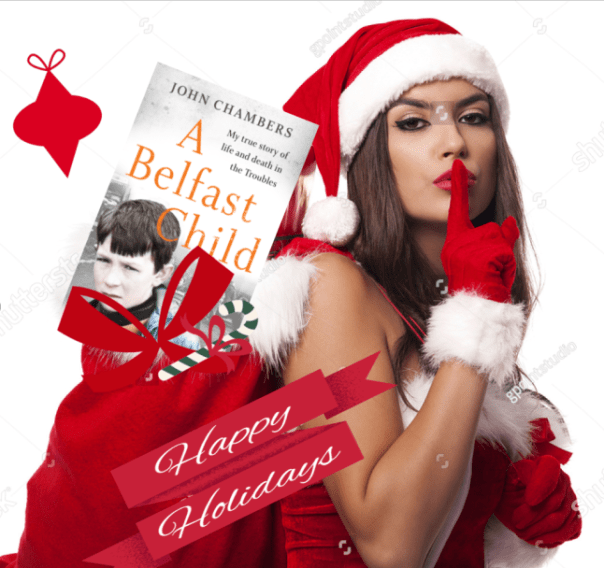

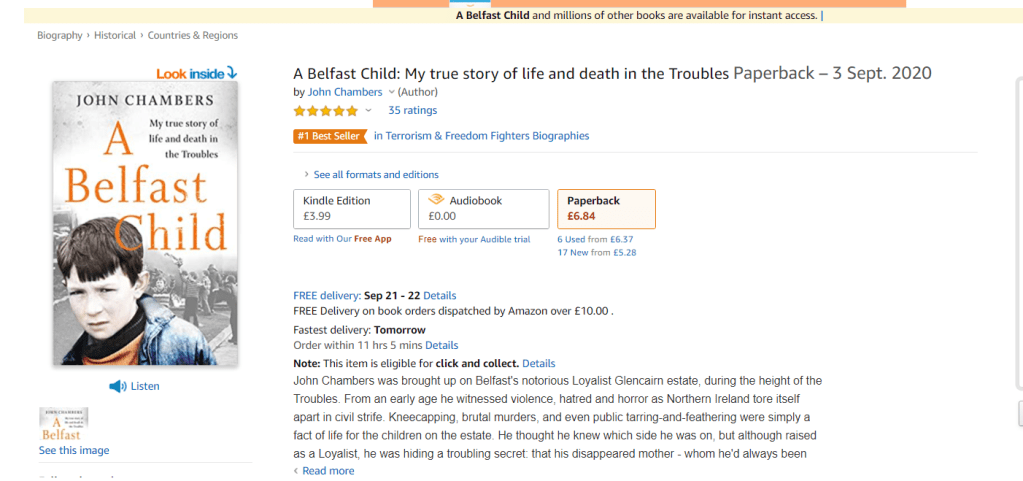

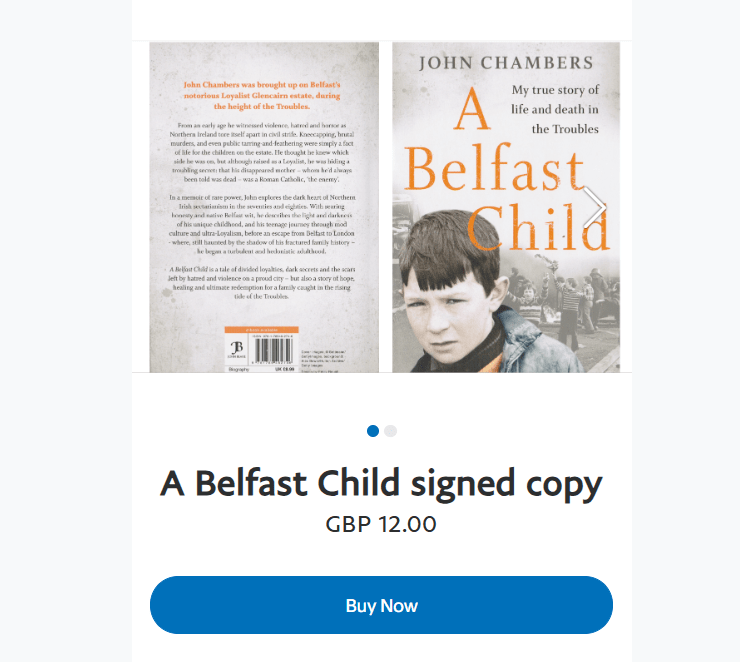

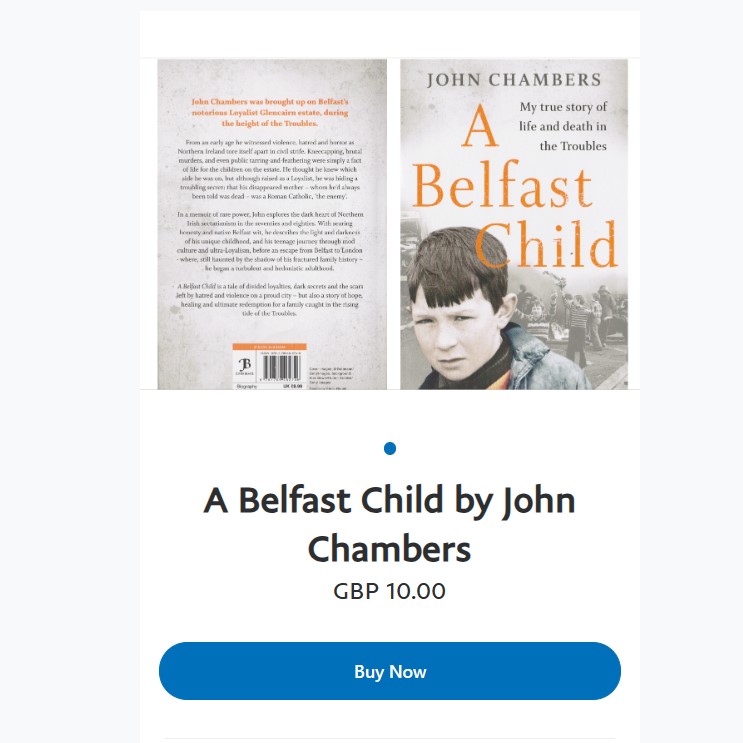

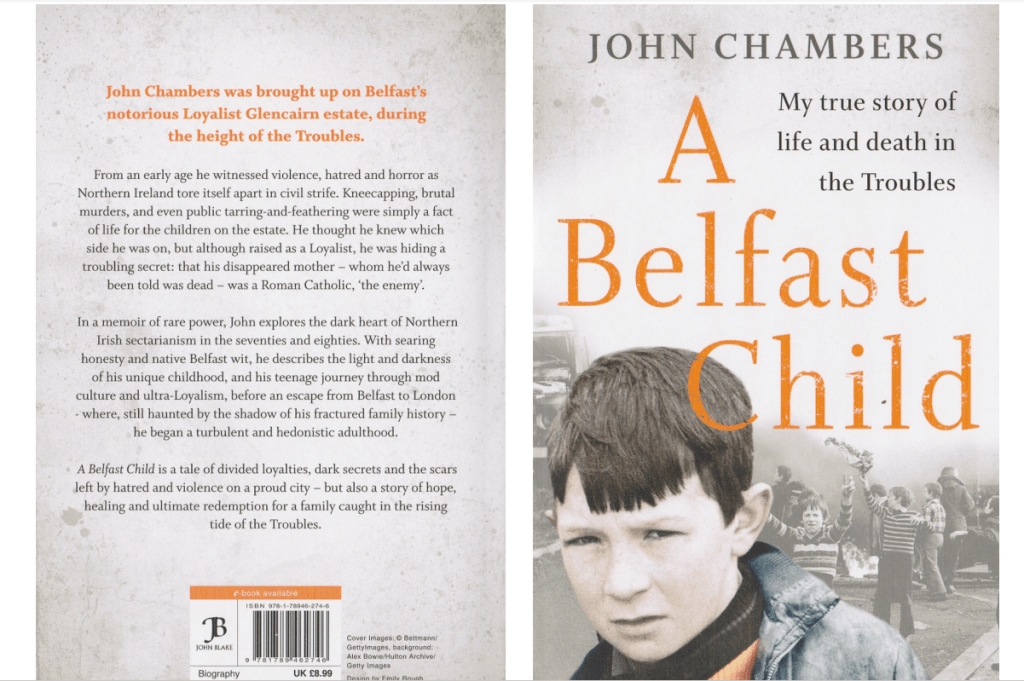

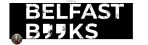

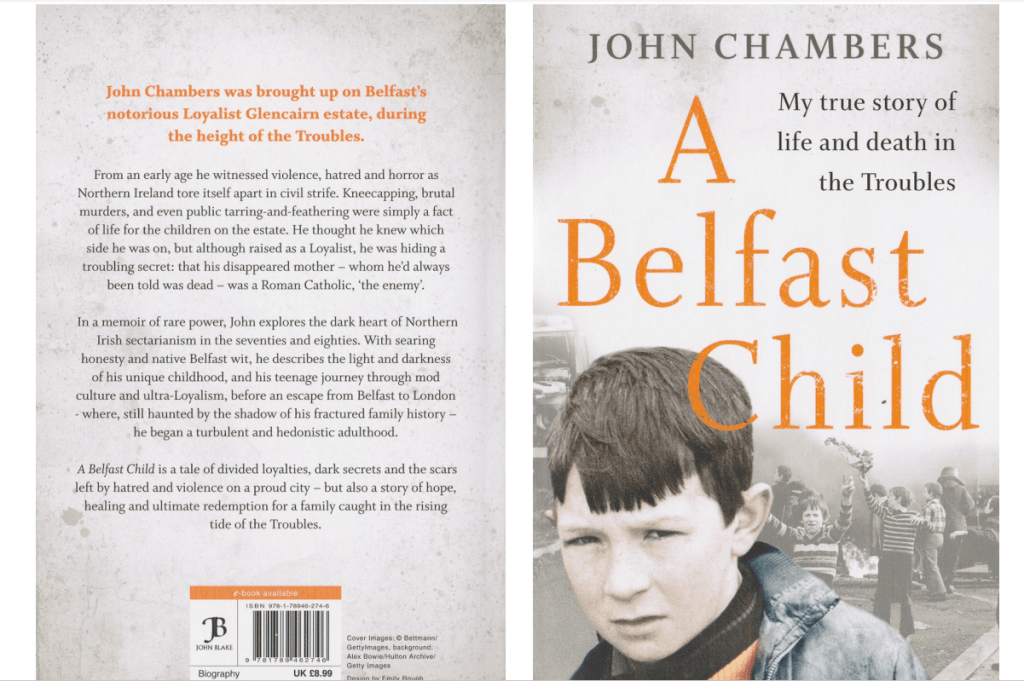

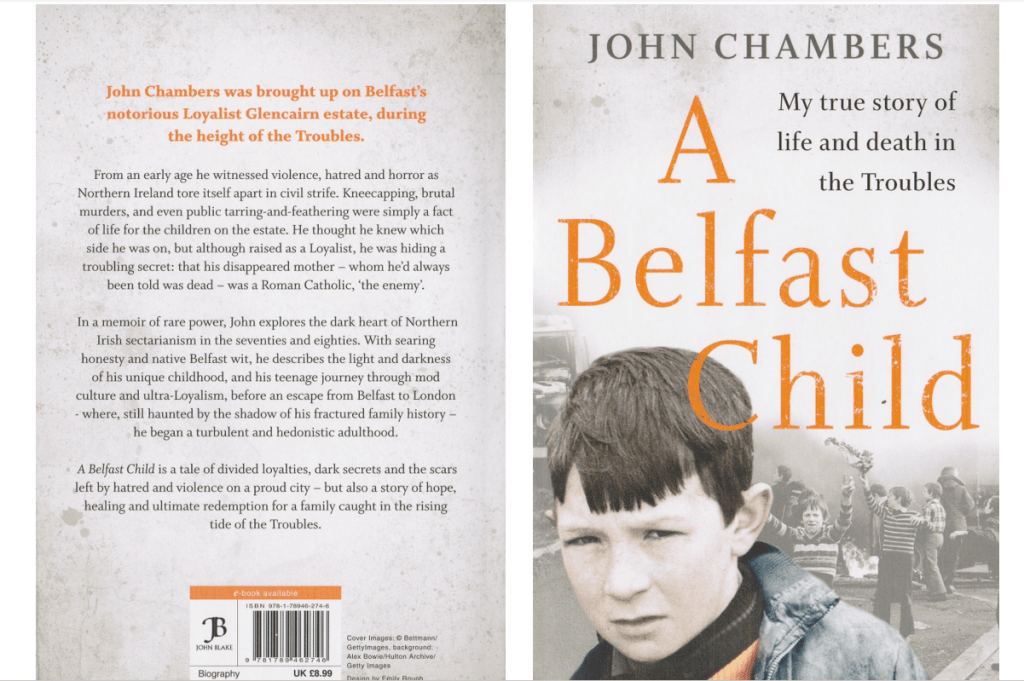

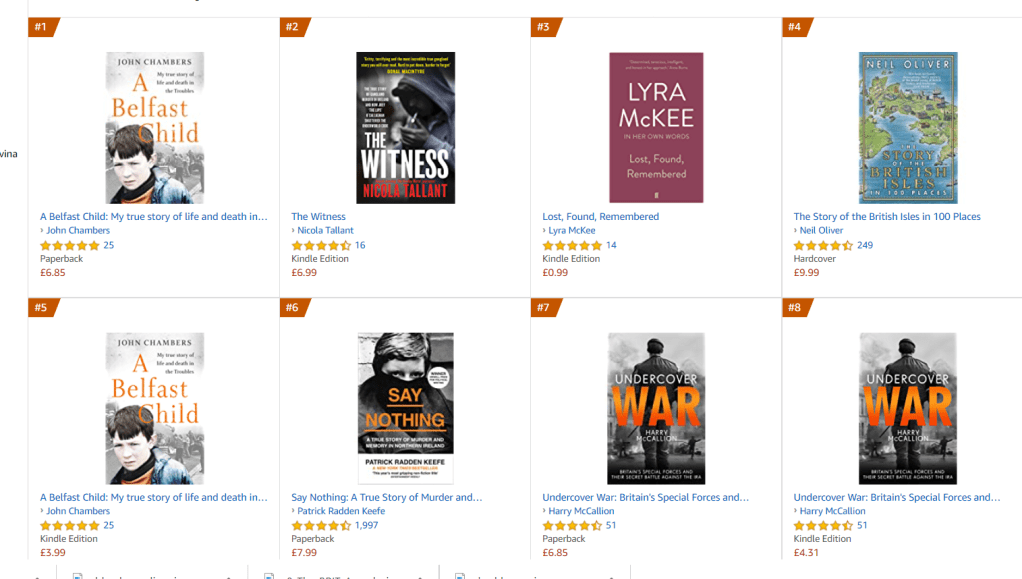

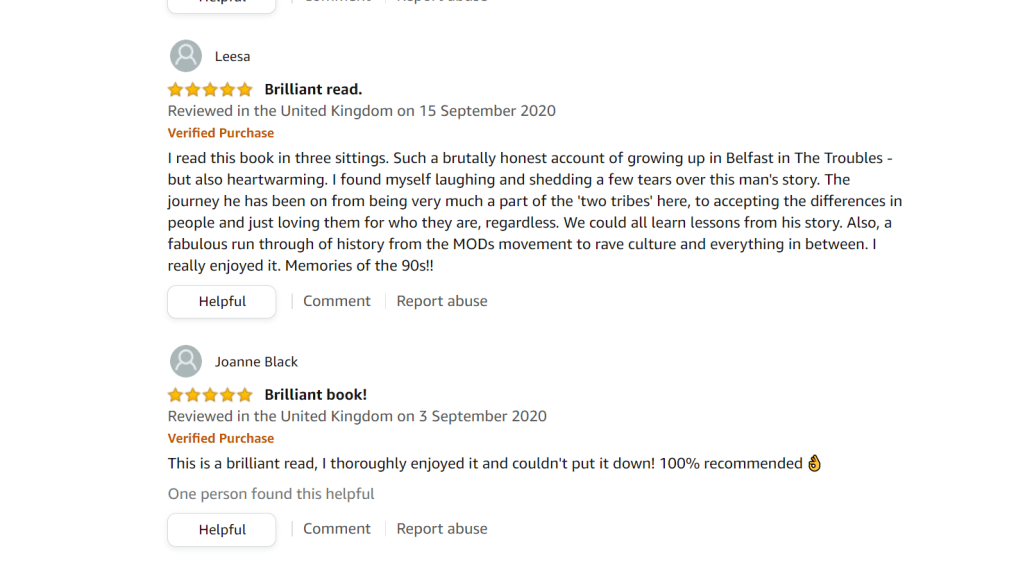

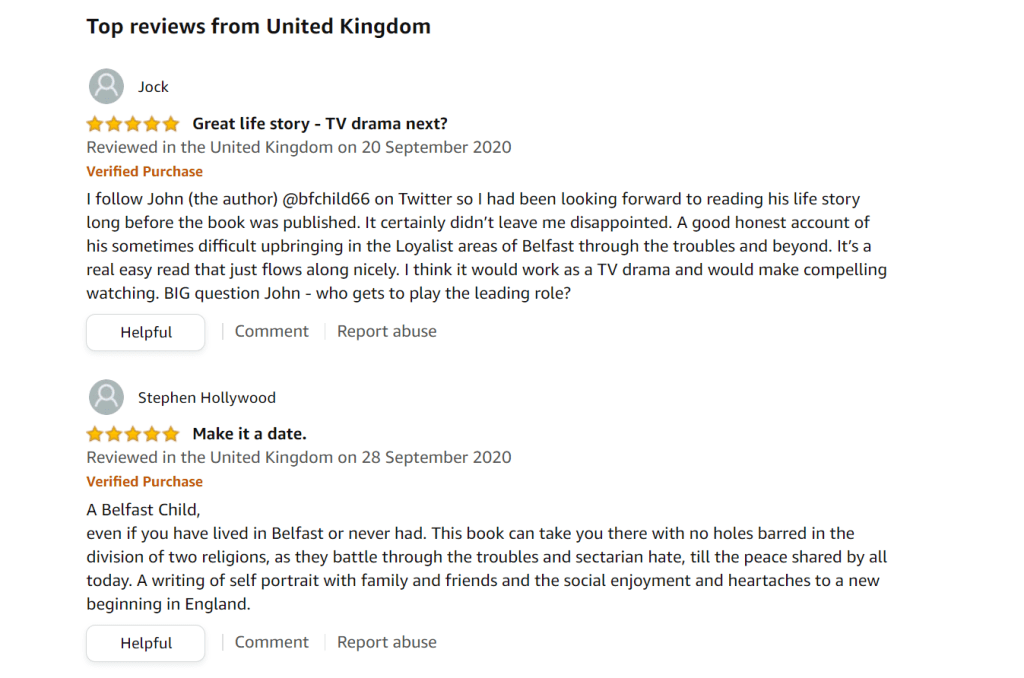

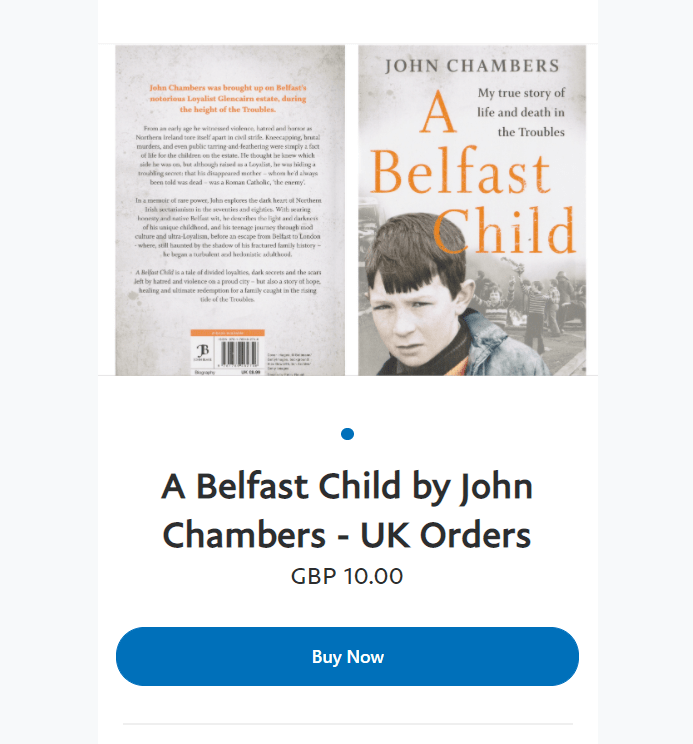

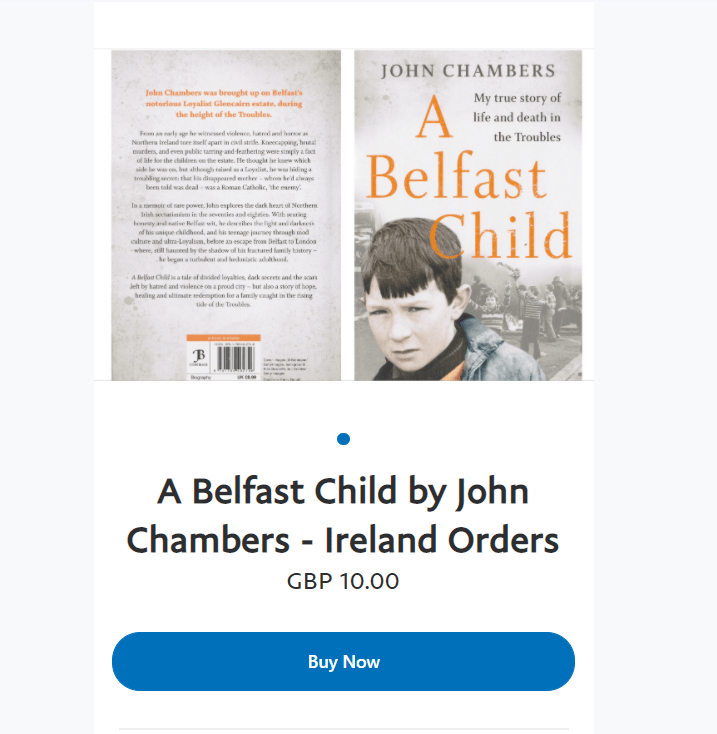

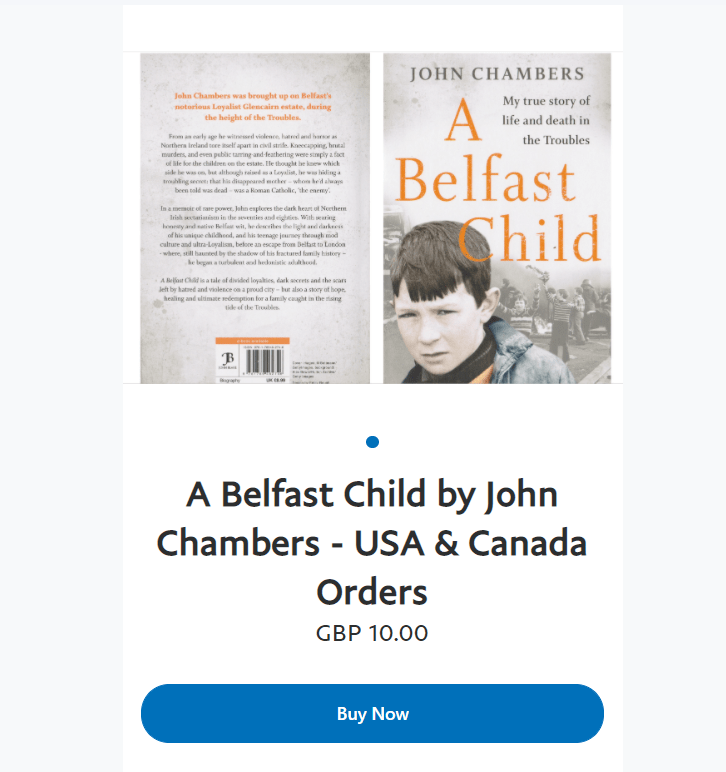

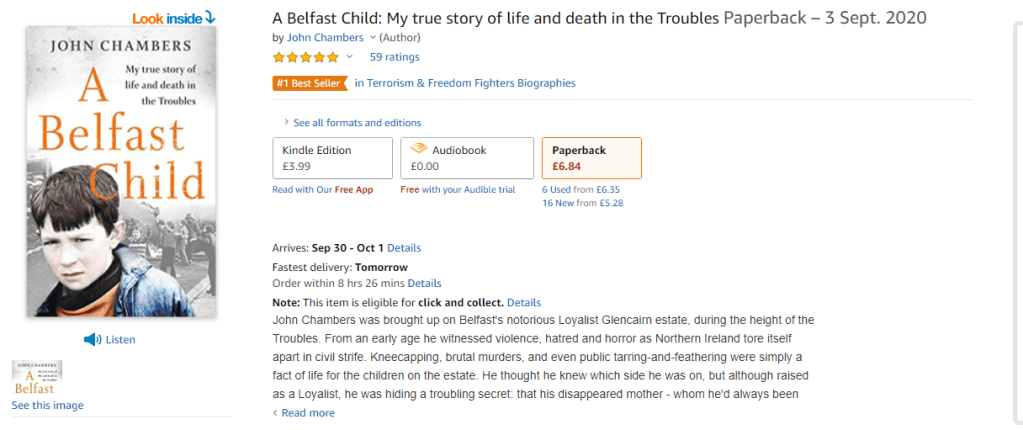

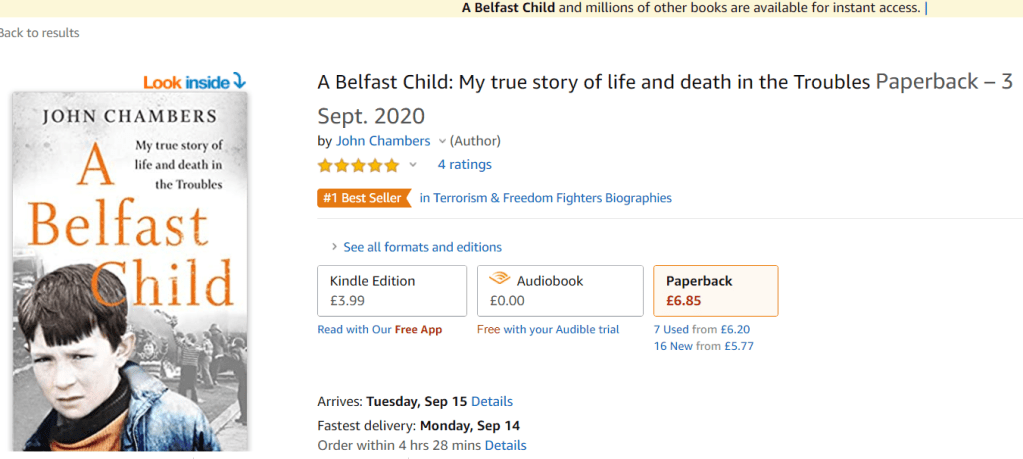

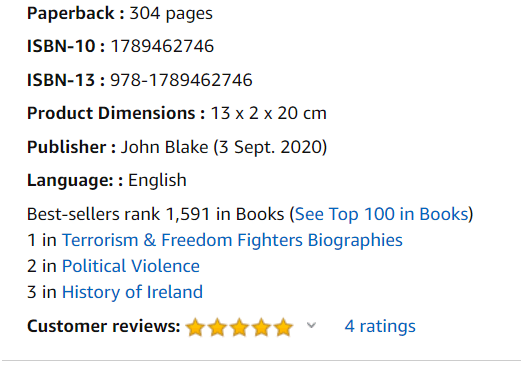

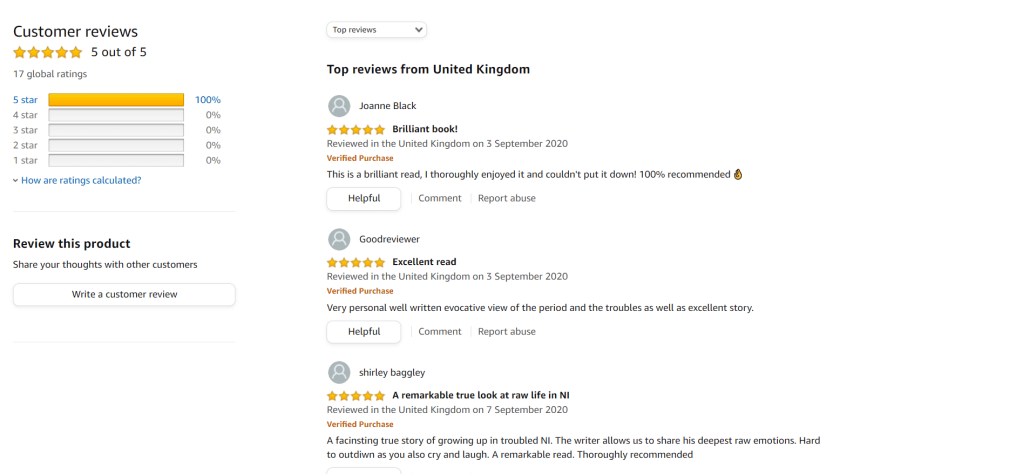

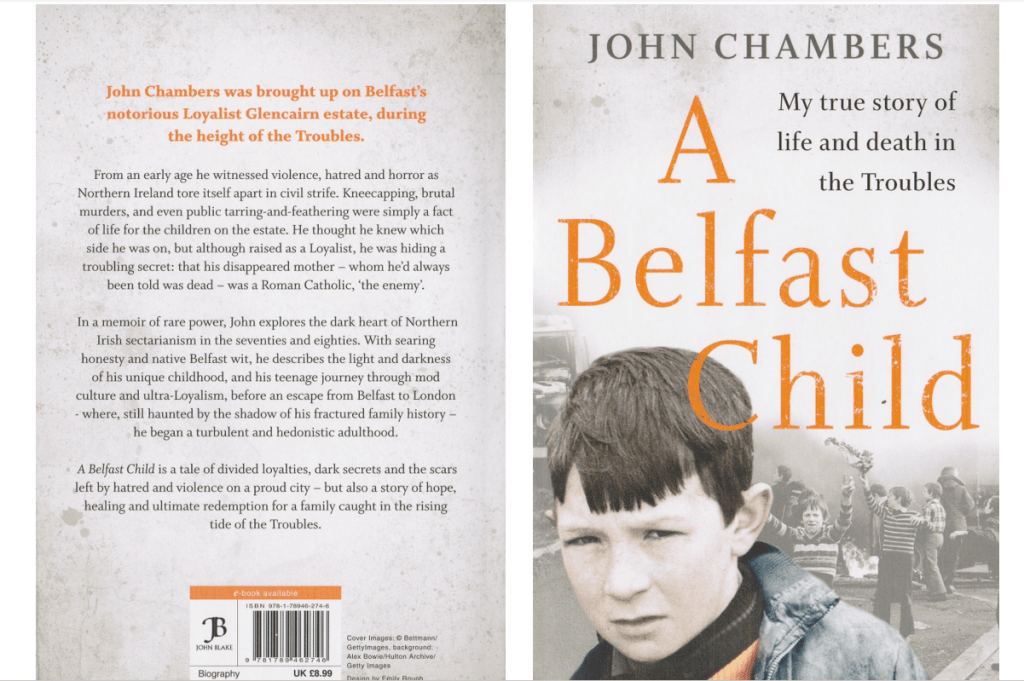

- A singed copy of my book for Xmas ?

Last chance to order before Xmas delivery cut-off period nxt Wednesday .

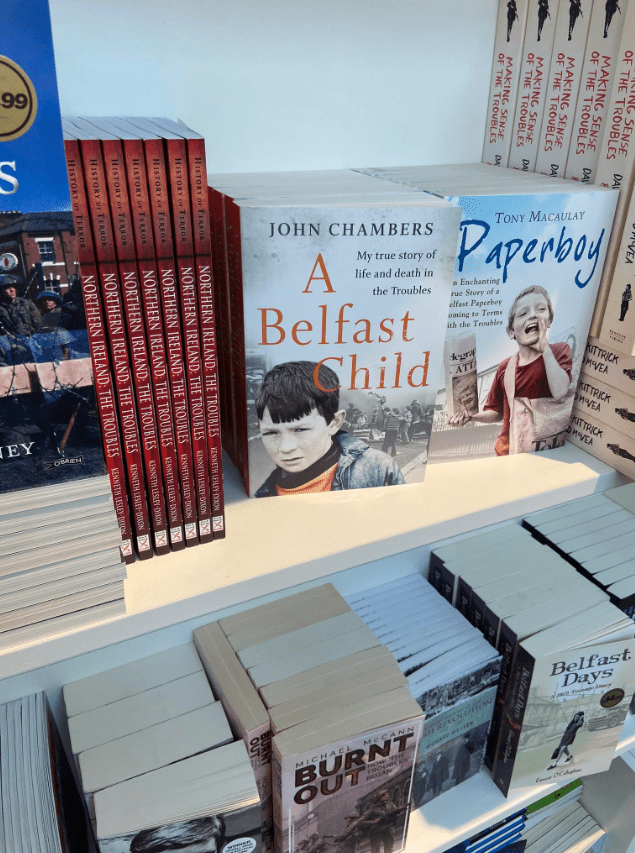

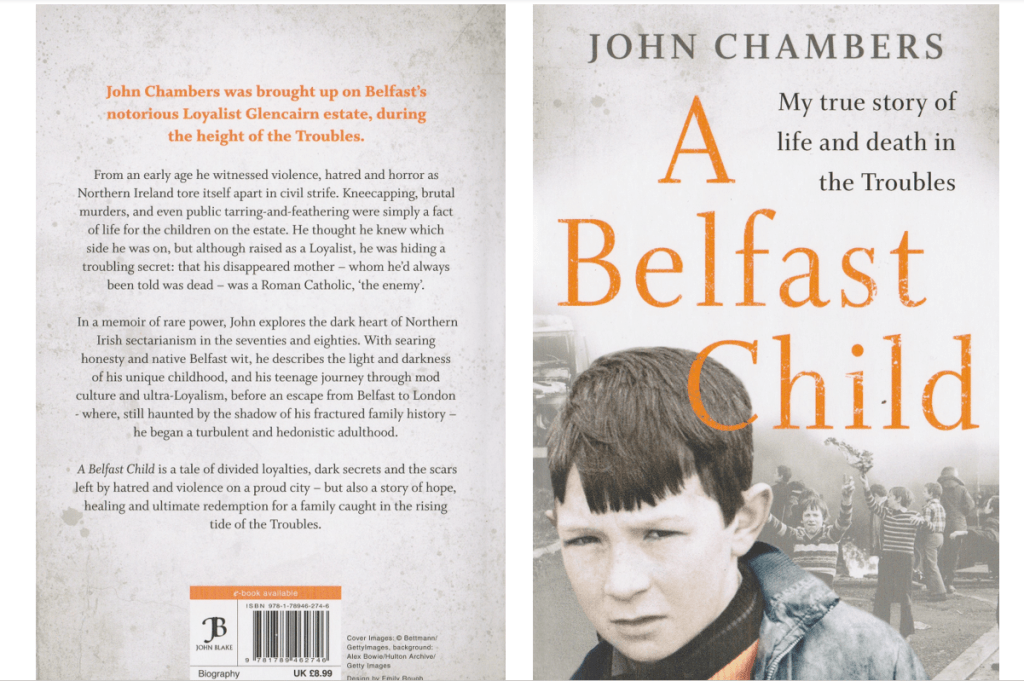

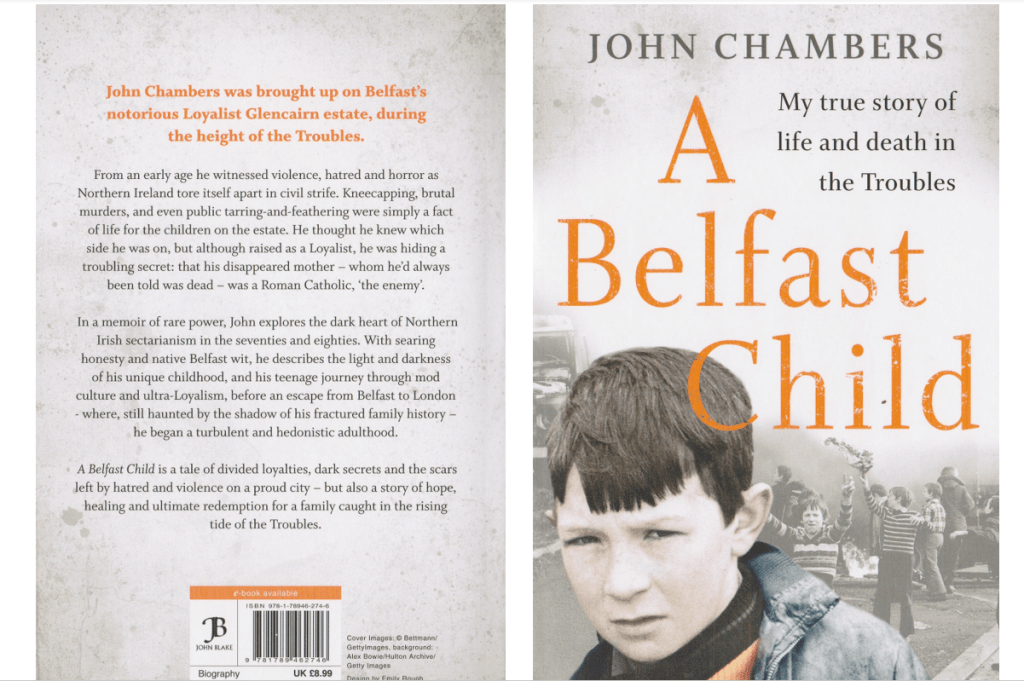

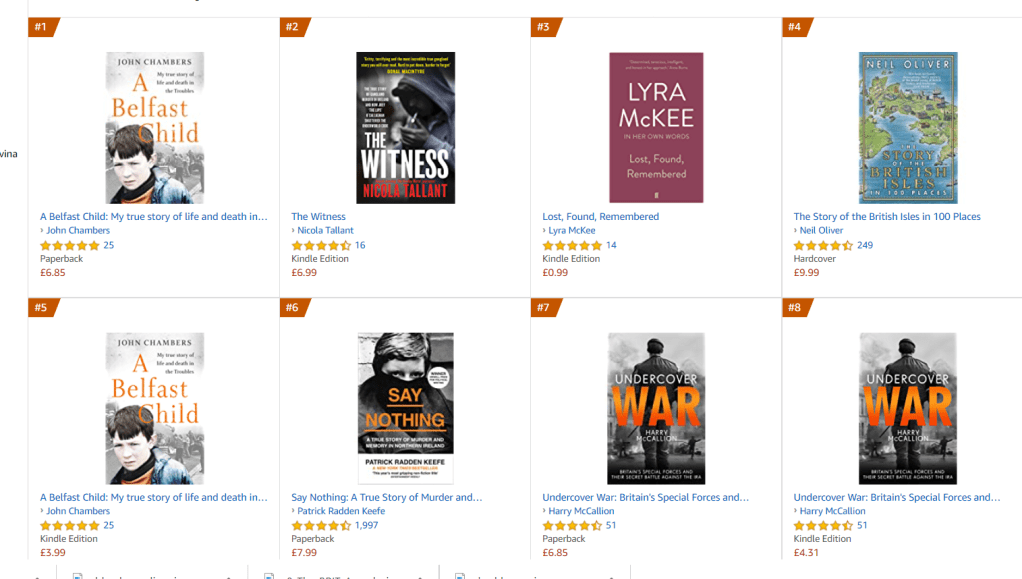

A personally signed copy of my No.1 Best Selling book : A Belfast Child , which may be worth a few quid if my story is made into a movie – watch this space !

UK Orders

Free postage for UK orders only !

For Europe & USA orders drop me a message below and Ill send you an payment link !

- I need some help folks 😜

And Im happy to bribe you with a free giveaway 🎁

Read on for more detail…

Ive doing a soft launch of my online shop : https://deadongifts.co.uk/ which I set up with my sister Mags and I need to drive some traffic to the store and start creating an online presence.

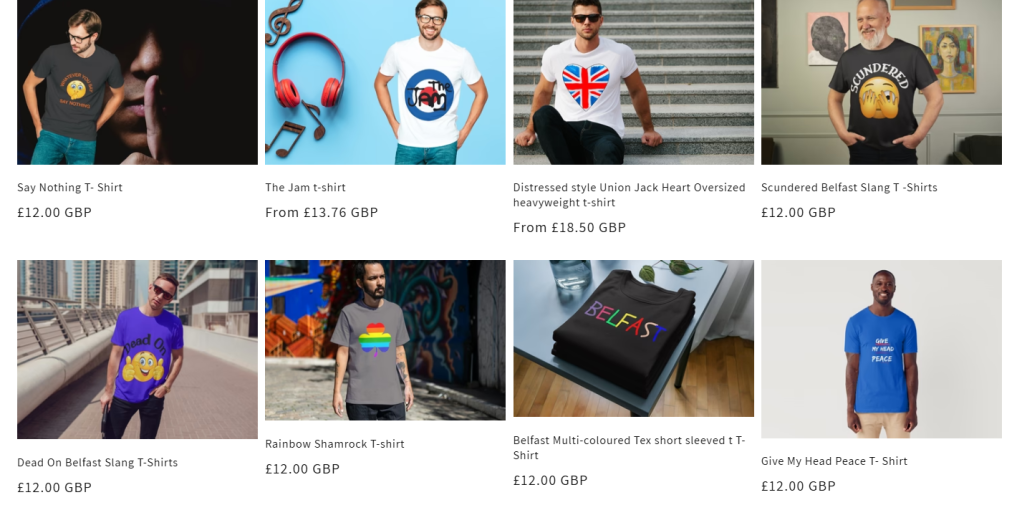

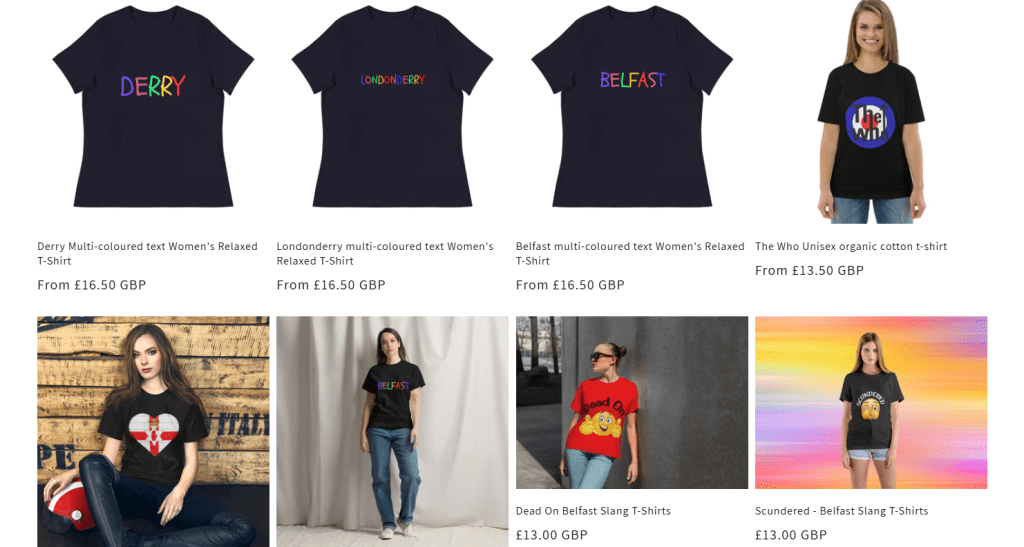

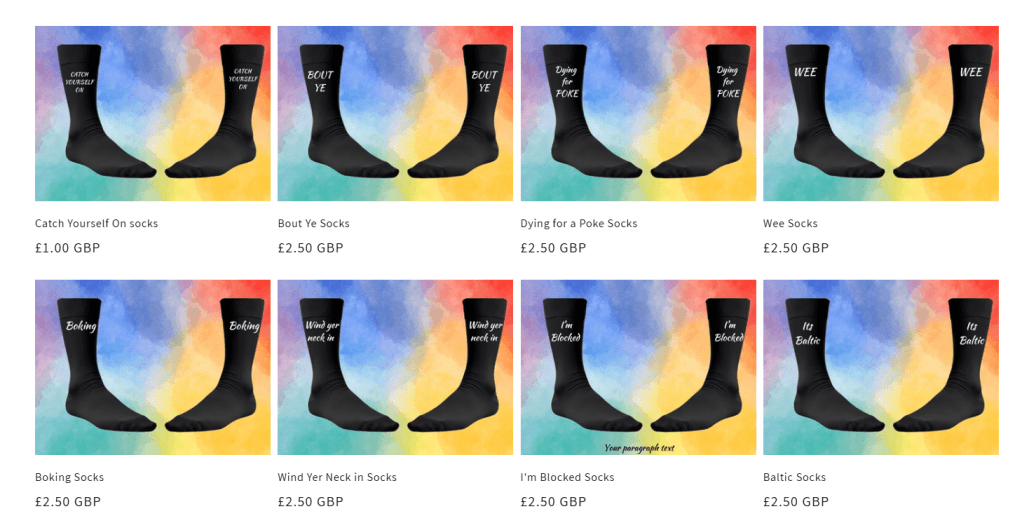

The shop will be mainly selling and promoting Northern Ireland themed gifts and souvenirs but as lifelong Jam fan and mod I cant help but add some designs and products based on my love of all things mod , the music, style and the culture I love it all .

We are currently still loading products and tweaking the website and this will be an ongoing process over the coming days and weeks. But feel free to have a nosey and buy anything that takes your fancy.

Now to the point of this exercise…

Ill be giving away 2 x £15 gift tokens to spend in the shop and/or two signed copy of my No.1 Best selling book: A Belfast Child in a a random draw of everyone who visits the shop and signed up for & subscribes to our emails alaerts . Dont panic we wont be sending you loads of promo sh*t just the occasional newsletter and updates on the shop and my crazy life .

Just visit the shop and sign up here : Dead On Gifts

Check out some of our current stock below .

Clock the image to visit page.

Male T -Shirts

Female T -Shirts

Belfast Slang Socks

Mugs & Cold Cups

Keyrings

Hats

Candles

That’s all for now folks , don’t forget to visit the store and sign up for our email alerts to be in with a chance of winning in our raffle , Ill announce the winners next weekend .

Visit the store: https://deadongifts.co.uk/

Thank you X

- Ireland’s Bloody History – Rathlin Island Massacre July 1575

l

Rathlin Island Massacre July 1575

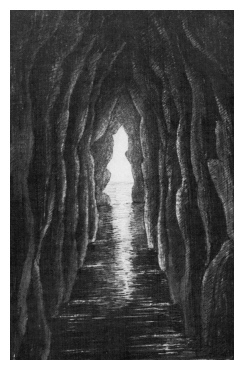

Bruce’s cave, one of Rathlin Island’s caves, etching by Mrs. Catherine Gage (1851) The Rathlin Island massacre took place on Rathlin Island, off the coast of Ireland on 26 July 1575, when more than 600 Scots and Irish were killed.

Sanctuary attacked

Rathlin Island was used as a sanctuary because of its natural defences and rocky shores; when the wind blew from the west, in earlier times it was almost impossible to land.

It was also respected as a hiding place, as it was the one-time abode of St. Columba.Installing themselves in Rathlin Castle, the MacDonnells of Antrim had made Rathlin their base for expanding their control over the north-eastern coast of Ireland in direct conflict with the local Irish and English resulting in several campaigns to expel them from Ireland.

Their military leader, Sorley Boy MacDonnell (Scottish Gaelic: Somhairle Buidhe Mac Domhnaill) and other Scots had thought it prudent to send their wives, children, elderly, and sick to Rathlin Island for safety.

Sir Francis Drake. Lauded to this day as one of the greatest heroes of Elizabethan England, he was one of the senior English officers at Rathin Island who ordered the slaughter of 600 unarmed civilians, much to Elizabeth’s approval.(National Portrait Gallery) Acting on the instructions of Henry Sidney and the Earl of Essex, Francis Drake and John Norreys took the castle by storm. Drake used two cannons to batter the castle and when the walls gave in, Norreys ordered a direct attack on 25 July, and the Garrison surrendered. Norreys set the terms of surrender, whereupon the constable, his family, and one of the hostages were given safe passage and all other defending soldiers were killed, and on 26 July 1575, Norreys’ forces hunted the old, sick, very young and women who were hiding in the caves.

Despite the surrender, they killed all the 200 defenders and more than 400 civilian men, women and children. Drake was also charged with the task of preventing any Scottish reinforcement vessels reaching the Island.

The entire family of Sorley Boy MacDonnell perished in the massacre Essex, who ordered the killings, boasted in a letter to Francis Walsingham, the Queen’s secretary and spymaster, that Sorley Boy MacDonnell watched the massacre from the mainland helplessly and was:

“like to run mad from sorrow”.

The Haunted Irish Island – Rathlin Island

Aftermath

Norreys stayed on the island and tried to rebuild the walls of the castle so that the English might use the structure as a fortress. As Drake was not paid to defend the island, he departed with his ships. Norreys realised that it was not possible to defend the island without intercepting Scottish galleys and he returned to Carrickfergus in September 1575.

Don’t forget to subscribe to my blog and follow me on Twitter @bfchild66

Secrets Of Great British Castles – Carrickfergus Castle

- Ireland’s Bloody History – Portadown massacre November 1641

Portadown Massacre November 1641

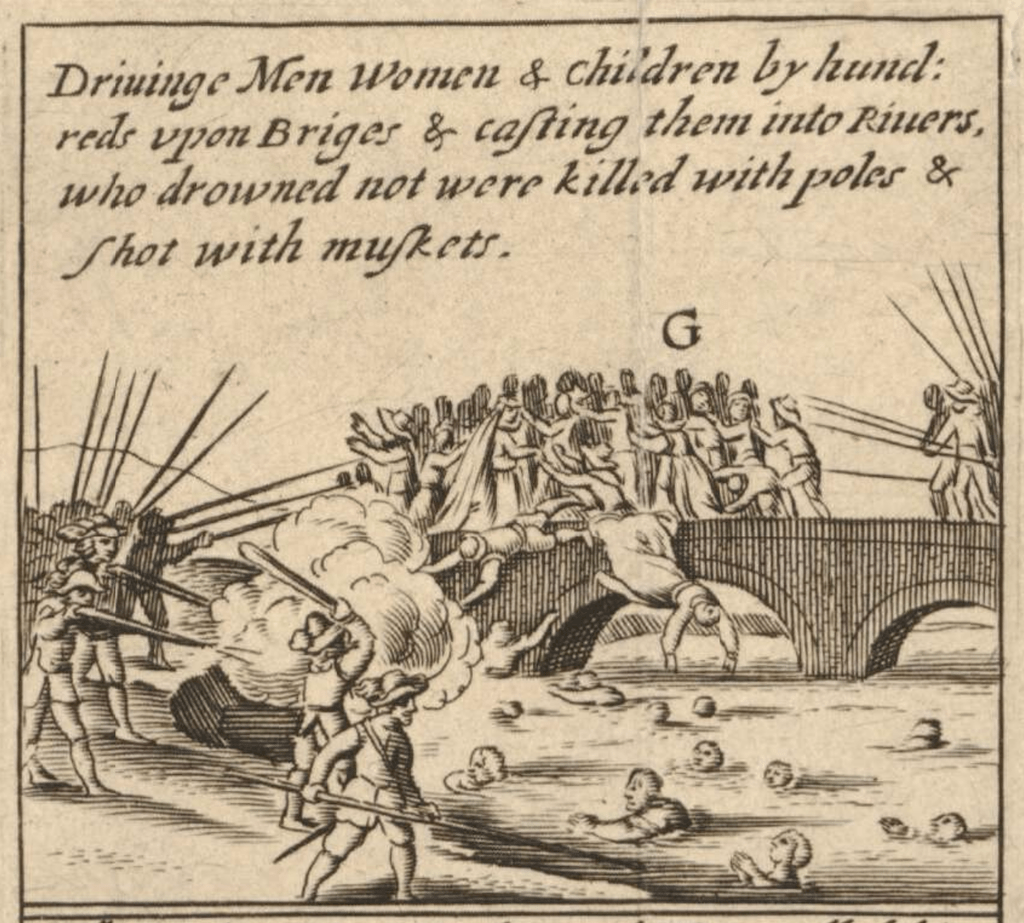

The Portadown massacre took place in November 1641 at Portadown, County Armagh, during the Irish Rebellion of 1641. Irish Catholic rebels, likely under the command of Toole McCann, killed about 100 Protestant settlers by forcing them off the bridge into the River Bann and shooting those who tried to swim to safety.

The settlers were being marched east from a prison camp at Loughgall. This was the biggest massacre of Protestants during the rebellion, and one of the bloodiest during the Irish Confederate Wars. The Portadown massacre, and others like it, terrified Protestants in Ireland and Great Britain, and were used to justify the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland and later to lobby against Catholic rights.

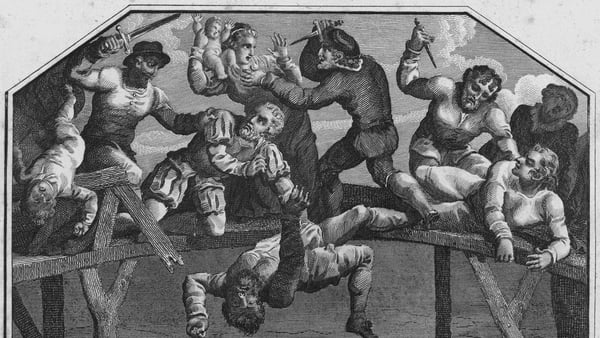

Engraving of the Portadown Massacre (1641) by Wenceslaus Hollar, first published in James Cranford’s Teares of Ireland (London, 1642) Background

The Irish rebellion had broken out in Ulster on 23 October 1641. It began as an attempted coup d’état by Catholic gentry and military officers, who tried to seize control of the English administration in Ireland. They wanted to force King Charles I to negotiate an end to anti-Catholic discrimination, and greater Irish self-governance, and to partially or fully reverse the plantations of Ireland. Many of those involved in the rebellion had lost their ancestral lands over the past thirty years in the plantation of Ulster.

Most of the land at Portadown had belonged to the McCanns (Mac Cana), a Gaelic clan. As part of the plantation, this land was confiscated by the English Crown and colonized by English and Scottish Protestant settlers.

Rebels, including the McCanns, captured Portadown on the first day of the rebellion along with nearby settlements such as Tandragee and Charlemont.

Some of the rebels began attacking and robbing Protestant settlers, although rebel leaders tried to stop this. Irish historian Nicholas Canny suggests that the violence escalated after a failed rebel assault on Lisnagarvey in November 1641, after which the settlers killed several hundred captured rebels. Canny writes,

“the bloody mindedness of the settlers in taking revenge when they gained the upper hand in battle seems to have made such a deep impression on the insurgents that, as one deponent put it, ‘the slaughter of the English’ could be dated from this encounter”.

Massacre

Portadown Massacre

Twenty-eight people made statements about the incident, but only one of them witnessed it. The others related what they had heard about it, including possibly from some of the rebels themselves.

William Clarke, the only survivor, stated that he had been held in a prison camp at Loughgall, where many of the prisoners were mistreated and some subjected to half-hangings. The rebels in the Loughgall area were commanded by Manus O’Cane. Clarke states that he and about 100 other prisoners were marched six miles to the bridge over the River Bann at Portadown. The wooden bridge had been broken in the middle. Threatened with swords and pikes, Clarke states the prisoners were stripped, and then forced off the bridge and into the cold river below. Those who tried to swim to safety were shot with muskets. Clarke claimed he was able to escape by bribing the rebels.

The massacre seems to have happened in mid-November. It is likely that the prisoners were being brought to the coast to be deported to Britain, and rebel leader Felim O’Neill had already sent other such convoys safely to Carrickfergus and Newry.

Sir Felim O’Neill of Kinard. Toole McCann was the rebel captain in charge of the Portadown area at the time, and several people made statements that he was responsible for the massacre. Hilary Simms writes:

“The convoy entered his area of control and it would seem likely that even if he did not order it, he and his men could not have avoided being involved in it”.

Native Irish tenants had already been massacred at Castlereagh, but Pádraig Lenihan writes there is no direct evidence the Portadown massacre was retaliation for this.

Aftermath

As word of the massacre spread, “elements of what happened were exaggerated, tweaked and fabricated”. People who heard about the massacre gave a range of death tolls, from 68 to 196. As Clarke was a witness of the massacre his figure of 100 is taken as being the most credible. Nevertheless, the Portadown massacre was one of the bloodiest in Ireland during the Irish Confederate Wars. About 4,000 Protestant settlers were killed in Ulster in the early months of the rebellion.

Irish Confederate Wars

In County Armagh, recent research has shown that about 1,250 Protestants were killed, about a quarter of the settler population there. In County Tyrone, modern research has identified three blackspots for the killing of settlers, with the worst being near Kinard, “where most of the British families planted … were ultimately murdered”.

There were also massacres of local Catholics, such as at Islandmagee in County Antrim, and on Rathlin Island by Scottish Covenanter soldiers. Though a supporter of British rule in Ireland, 19th-century historian William Lecky wrote:

“it is far from clear on which side the balance of cruelty rests”.

The massacre terrified Protestant settlers and was used to support the view that the rebellion was a Catholic conspiracy to massacre all Protestants in Ireland, though in truth such massacres were mostly confined to Ulster.

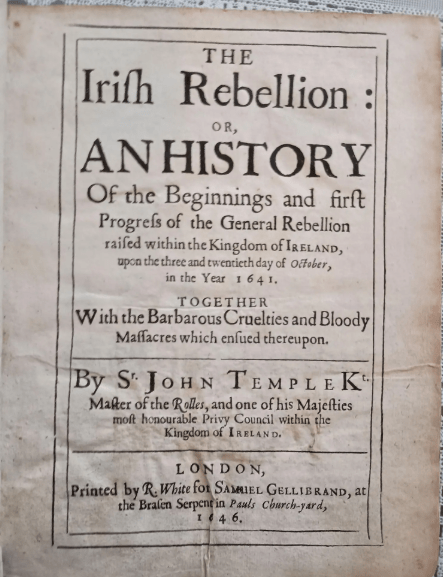

John Temple’s The Irish Rebellion (1646) In 1642, a commission of inquiry was held into the killings of settlers. Protestant bishop Henry Jones led the inquiry and read out some of the evidence to the English parliament in March 1642, although most of his speech was based on hearsay. The massacre featured prominently in English Parliamentarian atrocity propaganda in the 1640s, most famously in John Temple’s The Irish Rebellion (1646). Temple used the massacres at Portadown and elsewhere to lobby for the military re-conquest of Ireland and the segregation of Irish Catholics from Protestant settlers in Ireland.

Accounts of the massacre strengthened the resolve of many Parliamentarians to re-conquer Ireland, which they did in 1649–52. Massacres were committed by Oliver Cromwell’s army during this conquest, and it resulted in the confiscation of most Catholic-owned land and mass deportations. Temple’s work was published at least ten times between 1646 and 1812. The graphic massacres depicted therein were used to lobby against granting more rights to Catholics.

After the massacre, stories spread of ghosts appearing in the river at Portadown, screeching and crying out for revenge. These stories were said to have struck fear into the locals. One woman stated that Irish Confederate commander Owen Roe O’Neill went to the site of the massacre when he returned to Ireland in 1642. She stated that a female ghost appeared, crying for revenge. O’Neill sent for a priest to speak to the ghost, but it would only speak to a Protestant cleric from an English regiment

Toole McCann was later captured by English forces. He was questioned and made a statement in May 1653, saying he had not authorised nor seen the massacre, but had only heard of it. He was executed shortly after.

Don’t forget to subscribe to my blog and follow me on Twitter @bfchild66

Battle of Clontarf, 1014 – End of the Viking Age in Ireland

Main source: Wiki

- Here’s a complete chapter of my book…

For those who haven’t as yet read my No.1 Best Selling book here’s a free chapter

Intro

‘Historically, Unionist politicians fed their electorate the myth that they were first class citizens . . . and without question people believed them. Historically, Republican/Nationalist politicians fed their electorate the myth that they were second class citizens . . . and without question the people believed them. In reality, the truth of the matter was that we all, Protestant and Catholic, were third class citizens, and none of us realised it!’

Hugh Smyth, OBE (1941¬–-2014). Unionist politician.

Although I was raised in what is probably one of the most Loyalist council estates in Belfast, I was never what you might term a conventional ‘Prod’. Don’t get me wrong – coming from Glencairn, situated just above the famous Shankill Road and populated by Protestants (and their descendants) who fled intimidation, violence and death in other parts of Belfast at the beginning of the Troubles, I was (and remain) a Loyalist through and through. I was unashamedly proud of my Northern Irish Protestant ancestry (still am) and couldn’t wait for all the fun and games to be had on ‘The Twelfth’, or ‘Orangeman’s Day’ (still can’t). Even after thirty plus years of living away from the place my dreams are populated by bags of Tayto Cheese & Onion crisps, pastie suppers from Beattie’s on the Shankill and pints of Harp lager. I cheer on the Northern Ireland Football team (though I’m not a massive football fan, I watch all the big games) and I bitch frequently about the doings of Sinn Fein.

I’m a working-class Belfast Loyalist through and through and very proud of my culture and traditions. Yet from an early age I sensed that I was somehow different. As a child I couldn’t quite put my finger on it and when I discovered the truth in my early teens, I was embarrassed, mortified and ashamed – but maybe not particularly shocked. I always knew there was something not ‘quite right’ about me. The secret was that I wasn’t as ‘Super Prod’ as I thought; there was another strand of Northern Irish tradition in my background, one that was equally working-class Belfast, but as diametrically opposed to Protestantism as you’re likely to get. There’s a comedy song that probably still does the rounds in clubs across Ireland, North and South, called ‘The Orange and The Green’, the chorus of which goes something like ‘It is the biggest mix-up that you have ever seen/My father he was Orange and my mother she was Green.’ In other words, a Protestant father and a Catholic mother. This song could have been written about our family directly, so closely did it match our dynamic.

Now, if you’re reading this from the comfort of any other country than Northern Ireland, the Republic of Ireland or Scotland, you’ll be (just about) forgiven for wondering what all the fuss is about. Catholics marrying Protestants? So what? No big deal, surely. No one cares. But in a country like Northern Ireland, where tribalism still reigns supreme and the local people can sniff out a person’s religion just by looking at them, the prospect of the ‘mixed marriage’ is still cause for a good gossip, at the very least. During the Troubles period it was an excuse for deep embarrassment, banishment, a paramilitary beating, or worse. Those Protestants and Catholics who married and stuck it out either slunk away into some quiet corner of Northern Ireland, trying to ignore the ongoing conflict while hoping the neighbours wouldn’t ask too many questions, or left the place altogether, never to return.

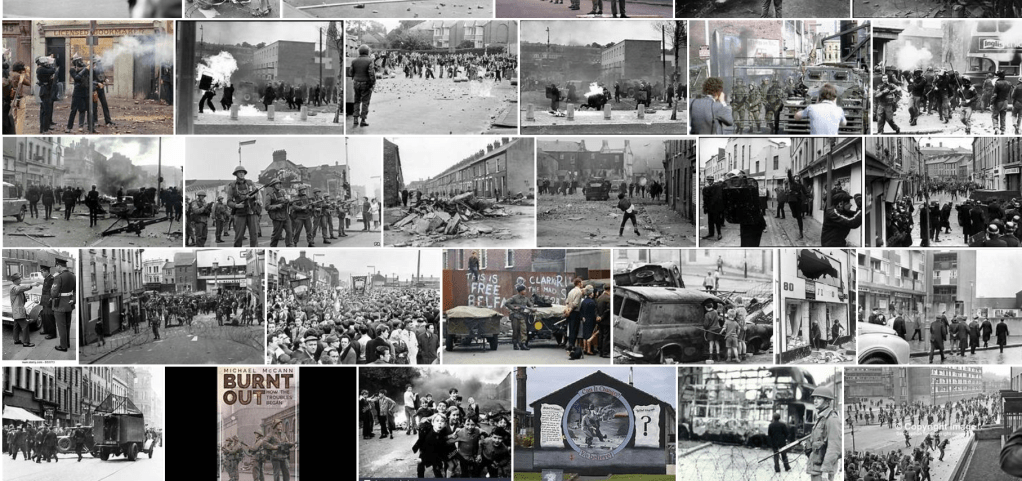

The marriage of my own parents, John Chambers (Protestant) and Sally McBride (Catholic), fell apart in the late 1960s as Belfast burned in the early days of the Troubles. The ferocity of hatred between the city’s two warring communities scorched many people desperately trying to find sanctuary in a country heading towards all- out civil war. As we’ll see, my parents’ marriage was among these early casualties. Their lives, and the lives of their four children, would change for ever and were shaped by the sectarian madness that tore Belfast and all of Northern Ireland apart and brought us all to the brink of an abyss that threatened and ruined our daily lives.

This isn’t a book about the day-to-day events of the Troubles. There are plenty of excellent histories available detailing the period in all its gory glory, and from all viewpoints. If you need deep context, I’d recommend reading one of these, or even visiting Belfast. It’s safe now and as a tourist you won’t find a warmer welcome anywhere on this earth. As we say, Northern Irish people are the friendliest in the world – just not towards each other.

Although I love history, I’m not a historian and I don’t intend this book to be a dry run through of the events of 1969 onwards. As a child I learned the stories and legends of the Battle of Boyne and the Siege of Derry at my grandfather’s and father’s knees, becoming immersed in the Loyalist culture that would shape and dominate my whole existence.

I just happened to be there at the time – an ordinary kid in an extraordinary situation made even more complicated by the secret of my dual heritage. This is simply the story of a boy trying to grow up, survive, thrive, have fun and discover himself against a backdrop of events that might best be described as ‘explosive’, captivating and shocking the world for thirty long years. I’ve written this book because even I find my own story hard to believe sometimes, and only when I see it on the shelves will I truly know that it happened. In addition, it’s a story I would like my own children and grandchildren to read. I want them to live in peace, harmony and understanding in a multicultural world where everyone tolerates and respects each other. I suppose I’ve always been a dreamer… . . . .

When they read my book, which I hope they will, they might understand what it is to grow up in conflict, hatred and intolerance, and work towards a better future for themselves and others. When I was twenty, twenty-one, I knew that if I didn’t leave Northern Ireland soon, I would end up either in prison or dead, or on the dole for the rest of my life. This was the brutal reality I was faced with. My own personal journey through life and the Troubles had led me to a crossroads in my life and I made the monumental choice to leave Belfast and all those I loved behind and start a new life in London.

I would hate to think my son, daughter or nephews and nieces back in Belfast would ever have to make the same drastic judgement about their own situation.

My Loyalist heart and soul respects and loves all mankind, and providing the God you worship or the political system you follow is peaceful and respectful to all others then I don’t have a problem with you and wish you a happy future. Just because I am proud of my Loyalist culture and traditions doesn’t make me a hater or a bigot; it just means I am happy with the status quo in Northern Ireland and wish to maintain and celebrate the union with the UK and honour our Queen and current King .

As a child growing up in Loyalist Belfast during the worst years of the Troubles, I hated Catholics with a passion and I could never forgive them for what I saw as their passive support of the IRA and other Republican terrorist groups. I didn’t or couldn’t differentiate between IRA and ordinary Catholics; such lines were blurred in my small Loyalist world. However, unlike many of my peers around me, I was never comfortable with the killing of non-combatants, regardless of political or religious background, and I mourned the death of innocent Catholics as much as innocent Protestants. In my childhood, I looked up to the Loyalist warlords and those who served them and when they killed an IRA member I celebrated with those around me. As I grew older and wiser my views changed. I no longer based my opinions and hatred on religion, but on politics and the humanity shown to others .

I’m a peace-loving Loyalist and therefore want everlasting peace in Northern Ireland. We do exist, despite perceptions from some quarters, but our voices are rarely heard, drowned out by the actions of the few, and certainly nowhere near as frequently as our Republican neighbours who are very much ‘on message’ with their own take on events. I hope this book goes some way to redressing that balance, and that whatever ‘side’ you might be on (or on no side at all) you will enjoy it, and that it will make you stop and think.

Finally, the story you are about to read is my own personal journey through the Troubles and my perception of growing up in Loyalist Belfast. In no way am I speaking for the wider Loyalist community or Protestant people and the views expressed here are my own. For reasons of security, some names have been changed.

John Chambers

England, April 2020.

Buy a sign copy of my book

Belfast Books stocks my book along with many other great titles.

Link to Belfast Books : https://www.belfastbooks.co.uk/

Buy me a coffee

Don’t forget to sign up to my blog for more great content 😜

Follow me on X : @bfchild66

- Norn Iron Olympic Winners 2024 👏👏👏

The 2024 Olympics in Paris were the most successful in history for athletes from Northern Ireland

Who are the Olympic medallists from Northern Ireland?

Daniel Wiffen

Gold: Men’s 800m freestyle Bronze: Men’s 1500m freestyle

Hails From: Armagh via Leeds

Daniel Wiffen (born 14 July 2001) is an Irish swimmer who competes at the Olympic Games, world championships and European championships for Ireland and at the Commonwealth Games for Northern Ireland. He is the Olympic and world champion at 800 metres.

Wiffen won gold at the men’s 800 metre freestyle final at the 2024 Summer Olympics in Paris, setting an Olympic record time of 7:38.19

] He won the 800 and 1500 metres freestyle at the 2024 World Aquatics Championships in Doha, the first time a male Irish swimmer had become world champion. He won the 400, 800 and 1500 metre freestyle at the 2023 European Swimming Championships (25m) in Otopeni, and the inaugural European Under-23 title in 2023 in Dublin.

Wiffen holds the 800 metres freestyle short-course world record with a time of 7:20.46.

Personal life

Wiffen was born in Leeds, England, and moved to Magheralin at the age of two. He has three siblings, twin brother Nathan, sister Elizabeth and another brother, Ben.. The family home is close to the border of County Down but is in County Armagh.

Daniel’s twin brother Nathan is also a swimmer who finished fourth in the 1500m at the 2024 European Championship and narrowly missed out on the qualifying time for that event for the 2024 Olympics.

Dan in Game of Thrones Daniel and his twin brother have a YouTube Channel. They both had minor roles in The Frankenstein Chronicles (season 1, episode 2) and Games of Thrones (season 3, episode 9); in the latter, their sister Elizabeth also appeared as Neyela Frey.

What’s my name? Daniel Wiffen, Olympic champion! | RTÉ Olympics Podcast Wiffen attends Loughborough University.

Main source : Wiki Daniel Wiffen

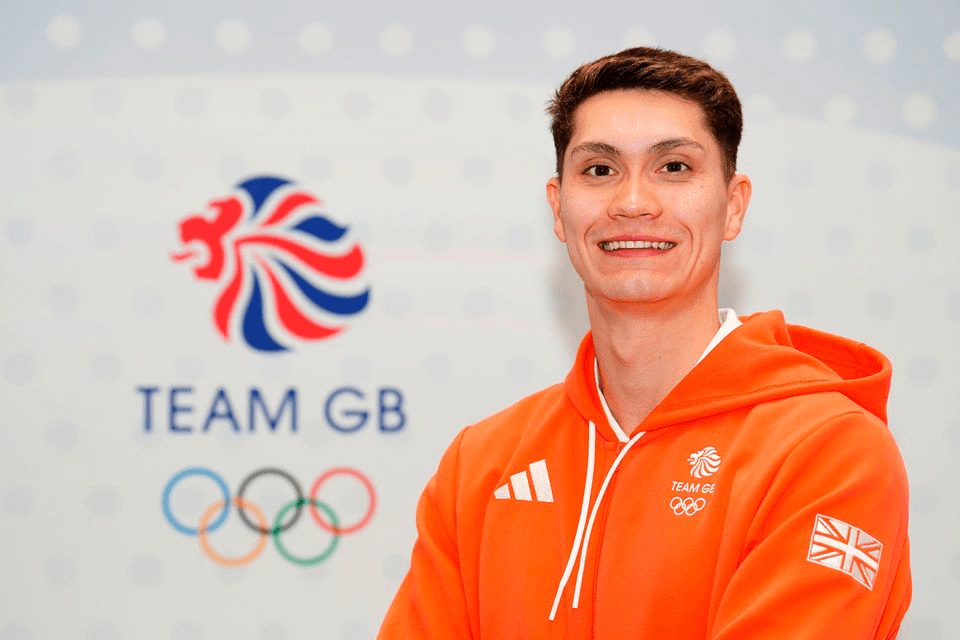

Jack McMillan

Gold: Men’s 4x200m freestyle relay

Hails From: Belfast

Jack McMillan (born 14 January 2000) is a swimmer from Belfast, Northern Ireland, who competed for Ireland in the men’s 4 × 200 metre freestyle relay at the 2020 Summer Olympics and for Great Britain at the 2024 Summer Olympics. He swam in the heats of the 4 × 200 metre freestyle relay and was awarded a gold medal when the British team won the final.

Personal life

“I was about four years old when I started swimming,” he said.

“My dad worked at the local leisure centre, so that’s how I got into swimming lessons.

“I started competing around eight years old and definitely had a natural feel for it compared to the other kids.

“It was that natural love at the start and knowing that I was quite a bit better than the other kids which spurred me on as well.

“I was always the best from an early age, and I wanted to continue that.”

Main Source : Wiki Jack McMillan

Main Source: Belfast Telegraph

Belfast Telegraph: Belfast swimmer Jack McMillan pays tribute to late mother as he shares first photograph of Olympic gold medal

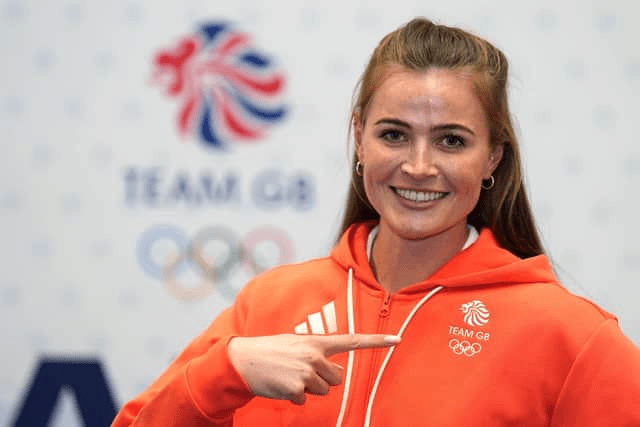

Hannah Scott

Gold: Women’s quadruple sculls

Hails From: Coleraine

Hannah Scott (born 18 June 1999) is a rower from Coleraine, Northern Ireland. She has won Olympic and world championship gold medals representing Great Britain

At the 2023 World Rowing Championships in Belgrade, she won the World Championship gold medal in the Quadruple sculls with Lauren Henry, Georgina Brayshaw and Lola Anderson. The team went on to win the gold medal in the quadruple sculls at the 2024 Paris Summer Olympics

Personal life

Who is Hannah Scott?

Team GB rower from Coleraine wins gold in Women’s Quadruple Sculls

Originally from Coleraine, Hannah’s Olympic journey began in the River Bann.

She started rowing at 13 at the Bann Rowing Club in Coleraine, one of the oldest and most successful rowing clubs in Ireland.

The historic club boat house has stood since 1864 in those years it has been the beginning of the road for many Olympic medals over the years.

Brothers Peter and Richard Chambers, who won silver together in the lightweight four at London 2012, and bronze-medal winning sculler Alan Campbell all started off at the Bann Rowing Club.

Having the opportunity to attend this club and be mentored by its accomplished coaches set Hannah up for success, and it was not long before she started to excel in the sport.

She went on to win five national titles and eight silver medals over several years of competition at the Irish Rowing Championships.

One of the biggest milestones in her rowing career was attending Princeton University in America, where she was able to take part in the university’s rowing programme.

While at the Ivy League university she went on to become a two-time Ivy League Champion in the Varsity Eight and she led the Princeton Women’s Crew as captain.

She also snagged two silver medals at the U23 World Championships.

The road to Paris

Her final years at university were disrupted by the Covid-19 pandemic, which opened up an opportunity for Hannah to return to the UK and earn a spot on the British Rowing Team at the delayed Tokyo 2020 Olympics.

The 25-year-old made her Olympic debut at Tokyo 2020 while still studying for her sociology degree at Princeton. Paris will be her second Olympics and she will be heading in as a reigning world and European champion in the women’s quadruple sculls.

Main Source: The Irish News

Main Source : Wiki Hannah Scott

Rhys McClenaghan

Gold: Men’s pommel horseHails From: Newtownards

Rhys Joshua McClenaghan BEM OLY (born 21 July 1999) is an artistic gymnast from Northern Ireland who competes internationally both for Ireland and Northern Ireland. He is recognised as one of the best pommel horse workers of his generation. He is the 2024 Olympic champion, the first gymnast ever to win an Olympic medal for Ireland. McClenaghan is also a double world champion on the pommel horse, having won gold in 2022 and 2023, the first Irish artistic gymnast ever to win world championship gold. In 2019, he became the first Irish gymnast to qualify to a world championships final and to also win a medal, taking bronze on pommel horse.

He is a three-time European champion and a Commonwealth Games champion on the same apparatus. McClenaghan is the first Irish gymnast to compete in a European final and also the first to win a European medal.

He also competed for Northern Ireland at the 2018 Commonwealth Games,[8] winning the gold medal on the pommel horse. He followed this by winning the 2018 European Championships, pipping the reigning Olympic and two-time world champion, Max Whitlock on both occasions. In 2023, McClenaghan won a second European title and retained the world title. His third European crown came in Rimini in 2024.

He is the first gymnast to become Olympic, World, European and Commonwealth champion on one apparatus.

He was named RTÉ’s Sportsperson of the Year for 2023.

Personal life

McClenaghan was born in Newtownards, County Down, to Tracy and Danny McClenaghan. Aged six, and already displaying a precocious aptitude for gymnastics, he started training at Rathgael Gymnastics Club in Bangor. McClenaghan later attended Regent House School in Newtownards. He has been coached by close friend Luke Carson for many years.

The family of Co Down gymnast Rhys McClenaghan have told of how they “knew this day would come” after he won gold at the Paris Olympics.

The Newtownards athlete completed on Saturday what is considered a gymnastics’ Grand Slam – World, European, Commonwealth and Olympic golds.

Speaking after her son stood on the winner’s podium to collect his gold medal, his mother Tracy said it was “the only one that was missing from his medal collection”.

The 25-year-old gymnast clinched gold for Team Ireland with his outstanding routine in the pommel horse final at the Bercy Arena. It came three years after he fell from the apparatus, when he was favoured to win gold at the Tokyo Olympics.

He said he had slept with the medal on his bedside table.

“It’s so heavy and so sharp I was scared I was going to wake up with injuries,” he said on Sunday.

“I started gymnastics at six years old, that gap between there, that is all my parents, that is them driving me to and from the gym, paying my gymnastics fees, everything they supported and wanted me to pursue that dream that I had.

“This medal is just as much theirs as it is mine.”

Main Source : Irish Time Rhys McClenaghan

Main Source : Wiki Rhys McClenaghan

Rebecca Shorten

Silver medal: Women’s four

Hails From: Belfast

Rebecca Shorten (born 25 November 1993) is a Northern Irish rower from Belfast. She is a world and European gold medallist and Olympic silver medallist for Great Britain.

She attended Methodist College Belfast and Roehampton University.

Personal life

‘I always knew Rebecca had right chemistry to be top rower at Olympics. Science teacher who coached Team GB silver medal star recalls conversation that set Belfast woman on course for glory

It was a conversation that changed Rebecca Shorten’s life and set her on the path to sporting stardom that culminated in a silver medal at the Paris Olympics.

The Belfast rower was part of the Team GB four that finished second in the final.

The team, also comprising Helen Glover, Esme Booth and Sam Redgrave, lost out on the line to the Netherlands by just an 18th of a second.

While their gold dream was dashed, there was a silver lining, boosting Northern Ireland’s medal tally on a day when Banbridge rower Philip Doyle and his partner Daire Lynch claimed double sculls bronze for Team Ireland.

Shorten’s story is remarkable, with her former mentor pinpointing a conversation 16 years ago that set her on a new course.

Enda Marron, her teacher and rowing coach when she was at Methodist College in Belfast, said her journey to the podium in Paris began after a science lesson in 2008.

“I was her chemistry teacher and she wasn’t the best chemist,” he told the Belfast Telegraph.

“She had handed in some chemistry work that wasn’t the best.

“It was okay, it just wasn’t the best, and she was a bit embarrassed by it and a bit shy about it.”

Mr Marron said he knew Rebecca wasn’t going to excel in a science career, but saw her potential as a rower.

He said: “I remember saying to her: ‘Who cares about chemistry? Let’s get you into a boat and down to the river’.

“After that she just went from strength to strength and the rest is history.”

At the time Shorten was only 14.

Sixteen years later, and she is the proud owner of an Olympic silver.

Mian Source : Jessica Rice Belfast Telegraph

Philip Doyle

Bronze medal: Men’s double sculls

Hails From: Banbridge

Philip Doyle (born 17 September 1992) is an Irish representative rower. He is an Olympian and won a medal at the 2019 World Rowing Championships. He raced in the men’s double sculls with Ronan Byrne at Tokyo 2020. He won a bronze medal in the men’s double sculls at the 2024 Summer Olympics with Daire Lynch.

Doyle went to St. Mary’s Primary School in Banbridge from 1996 to 2004. He then attended Banbridge Academy 2004-2011 where he played hockey winning the Bannister Bowl 2006, Richardson Cup 2007 & 2008, the McCullough Cup 2010 and Burney Cup 2010 & 2011. He played in a side which won the All Ireland Schools Cup 2011 and made the semi-finals of the European Schools Cup in 2011.

Doyle played for Ulster U16 at centre back when they were runners-up in an inter-provincial tournament. He represented Ireland U16 in the European championships coming 6th in Holland. Philip also played for Banbridge club up to first XI standard playing centre forward for the 2010/11 season.

Personal life

Doyle went on to study Medicine at Queen’s University in 2012. Philip did an intercalated degree in Medical Sciences in 2015/16 also graduating with a first class honours BSc. Philip got his senior debut for Ireland rowing in Lucerne, Switzerland in the men’s singles coming 15th. He and his partner Ronan Byrne went on to come 9th in Plovdiv, Bulgaria in the men’s double September 2018 delaying stating his Job as a doctor in Belfast city Hospital after Graduating from Queen’s University in July 2018.

Philip worked as a foundation 1 doctor in Belfast City Hospital December 2018 – April 2019 before returning to Rowing full time and competing at the European Championships in Lucerne, Switzerland with partner Ronan Byrne coming 9th

Speaking to the Belfast Telegraph last month Philip said: “So I train 18 times a week, anything from four to seven hours a day depending on the session structure and what competitions are coming up – and depending on my work.

“My training is always a mix of sessions in the boat, on the rowing machine or in the gym. The Elite Athlete Programme at Queen’s has certainly been a great support to me.

“At the beginning of the year I sit down with my coach and set out my goals and we then figure out how they can be achieved.

“My coach Mick Desmond worked tirelessly with me and with Queen’s Sport to facilitate my achievements and helped me work towards my senior international debut, in Lucerne last month, where I came 15th out of 27.”

In March, Philip was recognised for his heroic bravery following an incident on the Lagan last year. Alongside QUBBC teammates Chris Beck and Tiernan Oliver, Philip helped save the life of Terry Bell who had fallen into the river while they were taking part in a Lagan Scullers Club river race, on the morning of Saturday 25 November.

Philip was awarded the Students’ Union President’s Award for Student Achievement which recognises a student or group of students who have demonstrated excellence in leadership or have made a positive impact on society.

Main source : wiki Philip Doyle

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Philip_Doyle_(rower)

Main source : Queen University Belfast

Mary Peters Competes in Munich Olympics Dont forget to subscribe and follow me on Twitter 😉

- Should I Stay or Should I Go – Back to Belfast ?

Should I Stay or Should I Go ?

I’m torn between going or staying .

Throughout my time living and working in London and recent years in and around the North West of England it was always my long term intention that when I reached a ripe old age and my kids had settled into happy secure independent adult lives I would relocate to Belfast and spend the remainder of my time in the company of friends and loved ones and the Shankill community that has always been my spiritual home and where my heart and soul were forged within the heartlands and hallowed streets of loyalist Belfast .

You can take the boy out of the Shankill but you can’t take the Shankill out of the boy , Oh so true .

But as usual my path through life has seldom been straight forward and the Norms in their infinite wisdom and cruel nature weaved me a crooked path fluctuating between epic highs and soul destroying lows.

To be honest these past five years have been the most trying and stressful I’ve faced in decades of relative happiness and personal satisfaction and to say they have taken a toll on my mental and emotional wellbeing would be something of an understatement.

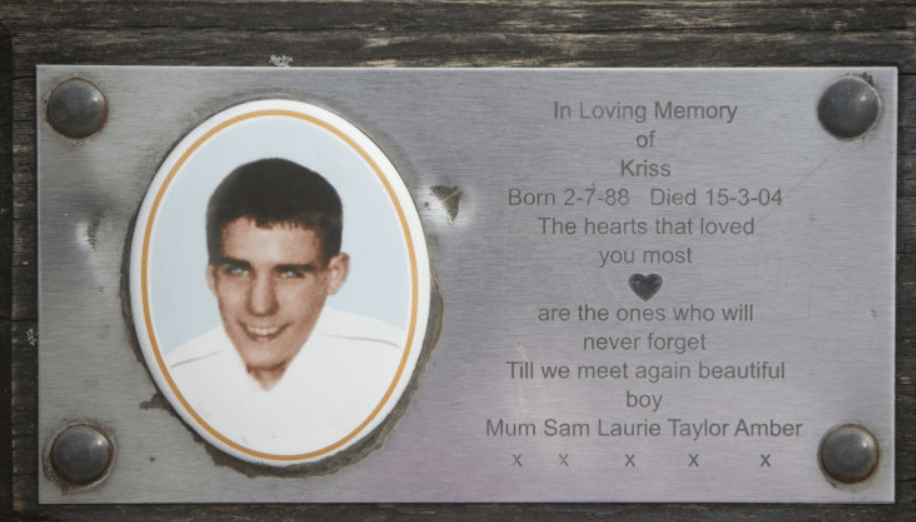

Looking back it all started to fall apart when I lost my much missed and loved mum to cancer, a heartbreaking period that I am still trying to come to terms with. If you are familiar with my history, you’ll know I spent many years not knowing if mum was alive or dead and the turmoil this caused throughout my early and teenage years is laid bare in my best-selling book A Belfast Child .

Come on – I had to get a plug in somewhere 😜

In fact back in the early 2000’s I was seriously considering leaving London altogether (I’d had enough of the rat race and a coke habit that was threatening to get out of hand ) and the possibility of moving back to Belfast and sorting myself out was one of two tempting options opened to me and my growing family. Mum was the second and she made it crystal clear she would love for me to live closer to her and help me get back on my feet . So I delayed my return home and we relocated to a little town on the outskirts of Preston, where we have lived since.

It was great to be so close to mum and we were able to spend quality time together getting to know each other and mending the damage of our tragic family history. The gravitational weight of my traumatic childhood has been a constant presence throughout my life and parts of my soul will always be held hostage to the past.

Nevertheless, this was one of the happiest and most productive periods of my life and at times it seemed I had an almost perfect life and wanted for nothing.

But as the years ticked by the pull of Belfast was becoming stronger and I missed and longed to be in the company of those I love and cherished above all others. Mostly I missed my three siblings and best mate “ Billy “ , we are supernaturally close and I grew to resent the years I had spent away from them.

And a little voice inside my head constantly reminded me that we were only given a brief spell on this mortal coil and time was running out.

Time keeps on slipping into the future

My biggest fear , a fear shared by all of us was that one of us might die prematurely and the landscape and future of our close family unit would be reshaped and destroyed forevermore.

After mums’ death the only thing keeping me in England was the fact my two children had been born and raised here and all their memories and historical roots were firmly planted in English soil . So once again I kicked the idea of the move home into the long grass and settled into the humdrum existence of daily life.

There were some high points during this period and after years of toying with the idea of seeing my story in print I finally managed to get a book deal and realised one of my long-held dreams. Subconsciously I think I was a little uncomfortable with publishing the book whilst mum was alive , although I had completed most of it back in the late 90s and she had read and approved of the early drafts.

As you may suspect this was not a straightforward process and there were many soul destroying bumps and rejections along the way but I persevered and much to my delight the book has went onto be a bestseller. Despite the popular misconception being a bestselling author has not made me rich , far from it and like many I struggle sometimes financially to make ends meet. Having said that I know the book will be my legacy and fingers crossed I’m working on a film script that I hope to sell in the coming years.

Stay tuned.

I will be covering the whole journey from concept to publication of the book in a future post and Princess Diana features in this story.

Life went on and my fragile soul struggled to deal with mums passing but always in the background I had my two sister’s supporting and comforting me from Belfast. Both desperately wanting me to return, and Jean was forever begging me to come home and to be honest I wanted nothing more. I began to feel trapped in England due to the dilemma of my children and the deep roots they had planted here, and I could see no way forward.

But the fates love to toy with the destinies of mortal men and the unpredictability of life weaved by the wicked Norns was about to shake my world to its very foundations and nothing would ever be the same. In the space of twenty four short months I lost three members of my close family, my uncle William, much loved brother in law Richard and the hardest loss of all my beloved big sister Jean. My grief and sorrow were biblical and the pain of losing Jean took me to dark places that hunt me still.

To make things even more difficult during this brutal period my “perfect” marriage of twenty-eight years was falling apart and suddenly I had to adjust to being a single parent and living alone in a life I had grown to detest.

To be completely honest these events are still too raw and painful for me to write about in-depth and I will leave them here for now. but I find the process of putting my thoughts on paper cathartic and will be covering these in a later post.

Oh , I almost forgot to mention in the midst of all this turmoil I was diagnosed with a potential life threatening brain aneurysm and I will cover this also in an upcoming post.

All these events have led me to a crossroad in my life and once again I am seriously considering moving back to Belfast permanently . Although I love England and its been good to me I have nothing left here but my children (and three legged cat) and they both understand and support my desire move back home. Autumn has now flown the nest and is settled with her new fella and yes I approve of him. Jude is a typical grumpy teenager and splits his time happily between his mum and me and as long as we feed him and give him money, he is happy with his lot and for me to move back to Belfast.

But it’s not that black and white for me.

He’s only seventeen and in my eyes still a child, although he thinks he’s a big man! I want to be there for him as he grows and matures and evolves as a young adult and be there to share and support him through the trials and tribulations life throws at him. I want to be there when he has he’s first pint in a pub , ( a regret I never had with my own dad) be there to pick him up when he falls down and be a constant presence in his life. Down the line when my children marry ( or not ) and have their own kids I want to be part of their lives and not a distant grandfather living over the Irish sea they see a few times a year. Also, since Jeans death Belfast has lost some of its magic for me as spending time with her was always a highlight of my trips home and in some ways I would feel guilty moving back when she’s not there.

So what am I going to do ?

Stay tuned and when I make up my mind Ill let you know x

That’s all for now folks, I’m pushing myself to write again as I’ve not put pen to paper in almost two years and I’m a little rusty and out of practice. . So be gentle with me please.

Upcoming posts :

The reasons I left Belfast.

Book writing process and publication

My movie script, where I’m at

Once upon a time in Northern Ireland, why thoughts and the process of taking part

My love of music and how its shaped my life

And much more…

- (no title)

my site now includes a comprehensive searchable database of every major event and killings during the Troubles.

Donate- The least visited page on my Blog - (no title)

- Belfast Child The Movie ?

I’m in the process of trying to complete a script based on my number one bestselling book A Belfast Child and to be completely honest I’m seriously struggling and becoming disillusioned with the whole process. Recently I feel like just admitting defeat, throwing the towel in and consigning the idea to the long grass.

But I’m not going to give up – just yet!

Since the book was published (and well before) I’ve been working on a script l based on my story (Philomena meets Trainspotting/Quadrophenia kind of theme) and I completed the first draft a few years ago. I sent this to Northern Ireland screen and some agents and the feedback I received was positive, but they suggested I needed to do some rewrites and changes to make it sellable before submitting it again. At the time I was going through some personal issues including my mum’s soul-destroying long illness and the publication of my book also took precedence, so I put the script on hold for a few years to focus on more pressing issues such as the daily grind of life and surviving all those little obstacles fate loves to throw in my path.

Earlier this year I thought I would give the script another go and have been working on it on and off since. It may surprise some of you to learn that putting together a script is an entirely different beast to writing a book and to be completely honest I’ve been really struggling with tweaking and amending it and its doing my head in !

I’ve reached out to a few folk in the industry and for one reason or another they cant commit to helping me complete this project. I’ve had meetings with established scriptwriters and producers and although they love the idea and praised the story none of them seem to have the time or resources I need to see this through to completion.

Also the success of Belfast the movie has put some of from taking up my story as they feel the market for Trouble’s themed stories has been saturated over the years and another Belfast story would be hard to place in the market. Obviously, I disagree with this and although I thought Belfast was a great movie it sugar coated the brutal reality of what life was really like back then whereas I feel my story/script incorporates the raw horror and unceasing violence that dominated our daily lives in the ghettos of Belfast and beyond and the legacy of the Troubles that still hunt us to this day. There was also much teenage madness and laughter which offered us some brief moments of escape from the violence all around us.

I’m waffling now so let me get to the point !

I have come to the conclusion in order to move my idea forward I need to bring in some professional help and with that in mind Im in the process of finding and engaging the services of a well-established script consultant and further down the line a script editor. These guys are in high demand and don’t come cheap but if I’m to have the best chance of seeing my script through to completion with professional input and guidance I’m looking at a fee of between £5000 – £10000 and possibly more down the line.

Despite popular belief being a bestselling author has not made me a millionaire (yet) or indeed anywhere near it and like many I face the same financial struggles that are the curse of the cost of living crisis we are all experiencing. But I have a long-held dream to see my story on the big screen and I am focused on pursuing this until I have achieved that aim. It took me almost twenty years to finally see my book in print and through all the ups and downs and soul-destroying rejections I persevered until one day a publisher took me onboard and the rest is history as they say. It was a long and hard process and there were many false starts along the way, but I eventually got there. I never give up on that dream until it became a reality, and I am going to apply the same determination and dedication in my quest to complete my screen play and see it on the big ( or small) screen one day. Hopefully within the next few years as Im getting old and my time is running out…

So that’s my mission statement and Ill be keeping you all updated via my blog and Twitter ( I just can’t get use to calling it X ) as and when I have something to share . It’s going to be a pain raising the fee for the services I need but one way or another I know Ill get there eventually.

If you’d like to be part of my story and are feeling wildly generous and excited about seeing me succeed and my project developed you can contribute towards the costs by clicking the donation button below.

If and when the movie comes out Ill give you all a mention 😜

Click donation button below to be a part of this awesome journey .

- Life was hard in the mean streets of Loyalist Belfast during the Troubles. Still is for many .

Extracts from my book A Belfast Child.

As I’ve said, the spell in gaol was towards the end of a long period of joyriding, shoplifting and drug-taking, some of which I was lifted for, many others that I got away with. In the 1980s, stealing cars and joyriding was almost a full-time occupation for many of Northern Ireland’s teenage males

This was the scenario one such Saturday night, when we jacked a car just for the hell of it. The experts could be in there with the engine started in five seconds flat, and there was little chance of being caught red-handed. We belted up the Crumlin Road, not bothering ourselves with red lights or pedestrian crossings, and celebrated reaching our home turf with a screeching handbrake turn, perfect in every technical sense except that it ended with a side-on smash into a nice new Opel Ascona car parked on the other side of the road.

None of us were hurt, but as we stared at the damage we’d inflicted on the Ascona we realised we’d committed a crime that could see us all shivering in fear as, one-by-one, our kneecaps were removed by a bullet from a Browning pistol. The car we’d just hit belonged to a top UDA man, a guy known to all of us as a character who took no nonsense, especially from a gang of hoods. Sensibly, we bolted from the car and ran as fast as our legs could take us.

Unfortunately, Glencairn is a small place and word quickly reached the UDA as to the identity of the joyriders. The following day we all received the inevitable summons to the community centre, where the paramilitaries were waiting. To say we were shitting it is an understatement.

‘Don’t even fuckin’ think of denying it!’ screamed the enraged commander

,when we tried to do just that. ‘If youse think you’re gonna get away with this, youse are more stupid that ye look!’With that, he pulled a pistol from his waistband. A couple of our gang started to cry. I could feel my balls disappearing into my stomach as I thought about the prospect of hobbling around the estate for the rest of my life.

‘Now,’ he said, brandishing the pistol in our faces, ‘did ye smash my car up or didn’t ye?’

Miserably, we nodded in unison. Our fate was sealed. Whatever happened to us next, we’d just have to accept. It was simply part and parcel of life in Loyalist West Belfast back then.

The commander looked us up and down, this group of shuffling, shaking, sniffling boys. Perhaps something about our pathetic appearance softened his heart. Maybe he realised that we’d not meant to do what we did, that it was an accident that only affected him personally, not the Loyalist movement as a whole.

‘Here’s what’s going to happen,’ he said, after watching us sweat for a minute or so. ‘I’m going to buy a new car, and every Saturday youse are gonna come up to my house and clean it inside and out. And if it’s still dirty, you’ll start all over again. You got that?’

I couldn’t believe what I was hearing. He was letting us off! Well, not quite, but washing a car was a whole sight easier than walking with a missing kneecap. We glanced at each other in shock, barely suppressing our smiles of relief,

–until the commander banged his fist on a table.‘And if I ever catch youse joyriding again,’ he said in a menacingly low tone, ‘there’ll be no question of what will happen to you. Got that?

!’We trooped out like a gang of monkeys released from a cage. And two Saturdays later we were at the commander’s house armed with buckets, sponges and cleaning liquid. After we finished, his was the shiniest car on the estate.

You have been reading extracts from my No.1 Bestselling book. If you’d like a signed copy see below. Ive got a special offer on this weekend . Only £10.00 plus free postage –

- Belfast Mods – In the 80s we give Peace a chance !

Becoming a mod in the early 80s during some of the worst years of the Troubles was a life shaping moment for me and for the first time ever I began moving away from the paramilitary run clubs and discos of my youth and meeting and socialising with my catholic counterparts in the city centre and beyond .

To be honest this was a real eye opening epiphany for me.

Prior to this and throughout my early life and teens I had been nurtured and raised exclusively within the loving tightknit tribal communities and social structures of the Shankill and surrounding areas. My tiny loyalist world was dominated by the Troubles and the so-called Peace Walls that separated our two warring war weary tribes. Like those around me my whole life and being was built on my pride in my unionist culture and British identity . Back them paranoia between Catholics and Protestants was off the scale and as a kid growing up when and where I did I couldn’t differentiate between ordinary Catholics and republican killers. Such lines were blurred in my little loyalist world, and like my peers who also grew up in the ghettos of Belfast I knew no different. But as I grew older and wiser my myopic view of Catholics gradually changed and this was largely due to me becoming a mod and starting to spread my wings for the first time and explore the teenage pleasures other parts of my city might offer. Music truly is a universal language and for me it was a glorious unifying force that broke down the barriers that had held me back thus far and I was ready to embrace it all and party like never before.

What follows is one of the Mod chapters from my book A Belfast Child. See below on how to get your hands a personally signed copy.

Chapter 12

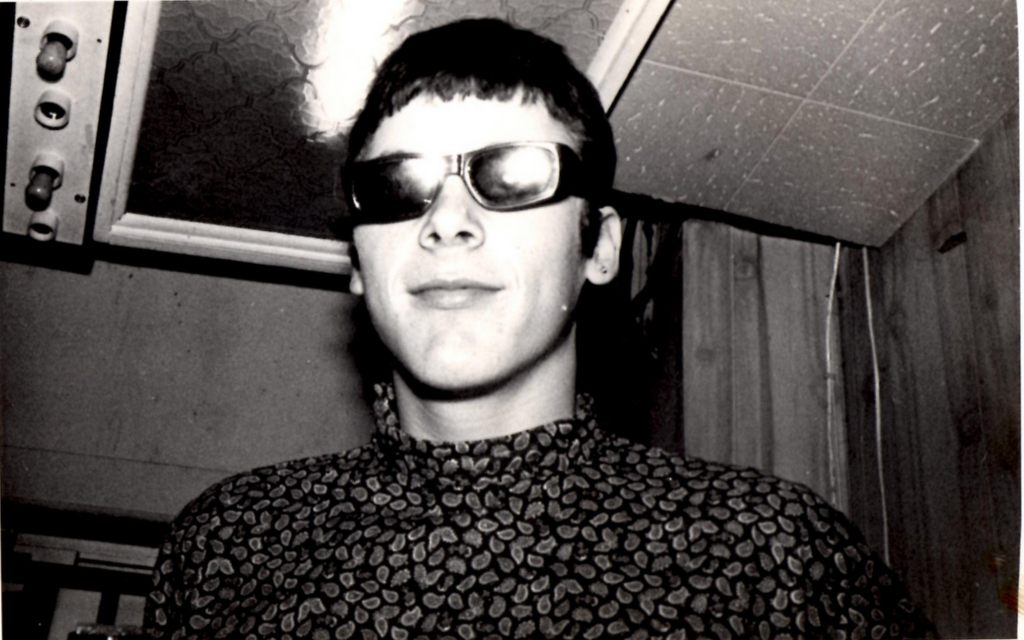

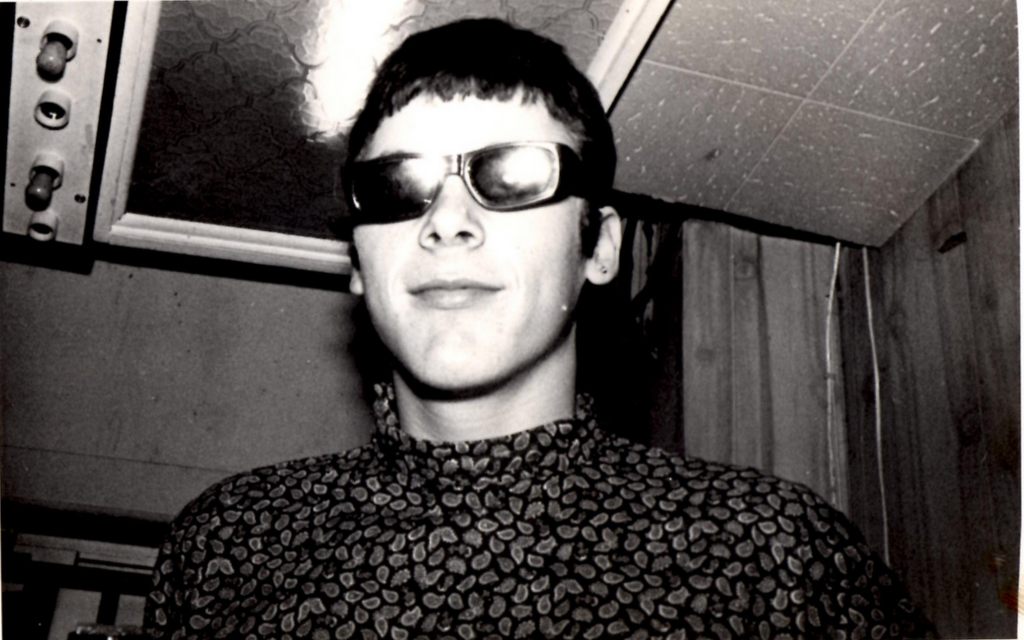

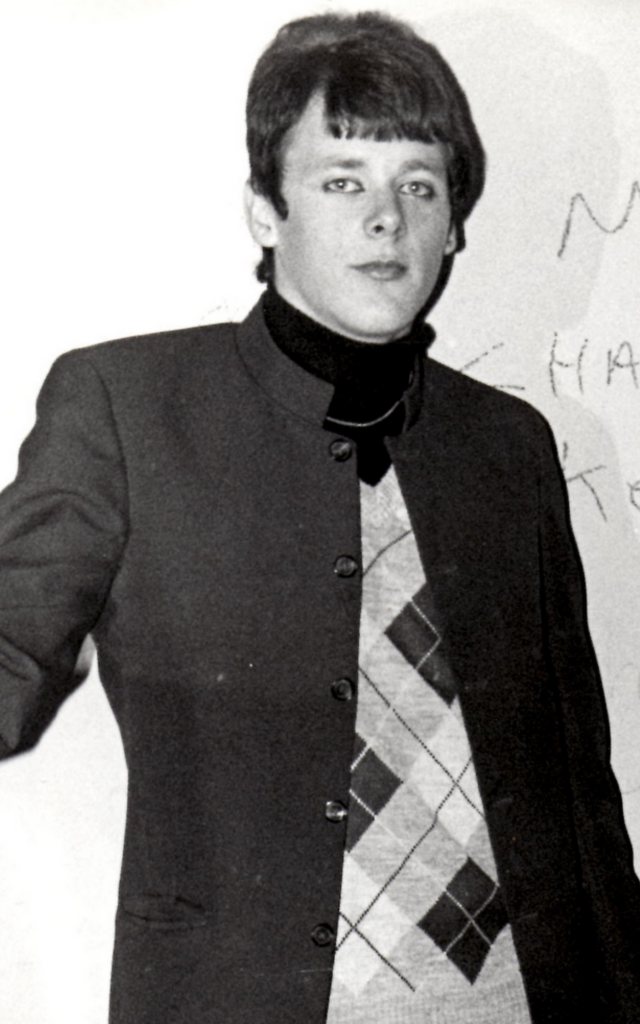

Me as a cool mod

Owning the scooter meant I no longer had to wait for buses or black taxis that never arrived, or risk walking through heavily Nationalist areas where my eyeliner and beads would attract very unwelcome attention. It was bad enough walking down the Shankill in all the clobber; skirting the Ardoyne or Unity flats as a Loyalist in a paisley-patterned shirt was sheer suicide.

The Merton Parkas ‘You Need Wheels’ TOTP (1979)

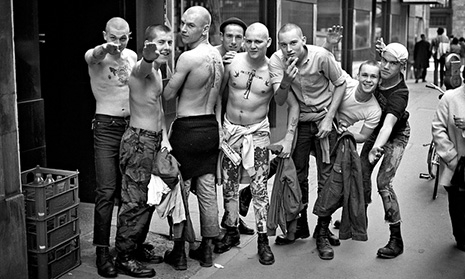

Of course, Mod as a movement wasn’t confined to us Prods. We knew that a sizeable number of Belfast Catholics were also into the clothes, the music and the drugs. I’m guessing that not many of them wore Union Jack T-shirts or had red, white and blue roundels painted on their parkas like we did, but aside from that they were just the same as us.

Jacqueline’s photographs show gangs of boys and girls congregating in several spots around Belfast and no one has ‘Catholic’ or ‘Protestant’ tattooed on their forehead. All we see is a gang of young kids smiling, laughing and having fun together – just as it should be when you’re that age.

Belfast Mods outside the city hall 1980s

Mod took no notice of religion. There was no place for hatred or division among the scooter boys and girls who gathered on a Saturday afternoon by the City Hall, or drank in the Abercorn bar in Castle Lane (which, ironically, was the scene of an infamous IRA bombing in 1972 that killed two young Catholic women and injured 130 other innocent people – a particularly disgraceful act in a terrifying year). Sectarian insults and deep-rooted suspicions were put aside when Mods from both sides of the fence danced at the Delta club in Donegall Street or drank strong tea and smoked fags in the Capri Cafe in Upper Garfield Street. When Mods gathered, there was no time for this kind of talk. Hanging out, being cool and looking sharp were the only things Mods were interested in. For those moments, all the violence and oppression and misery were put aside.

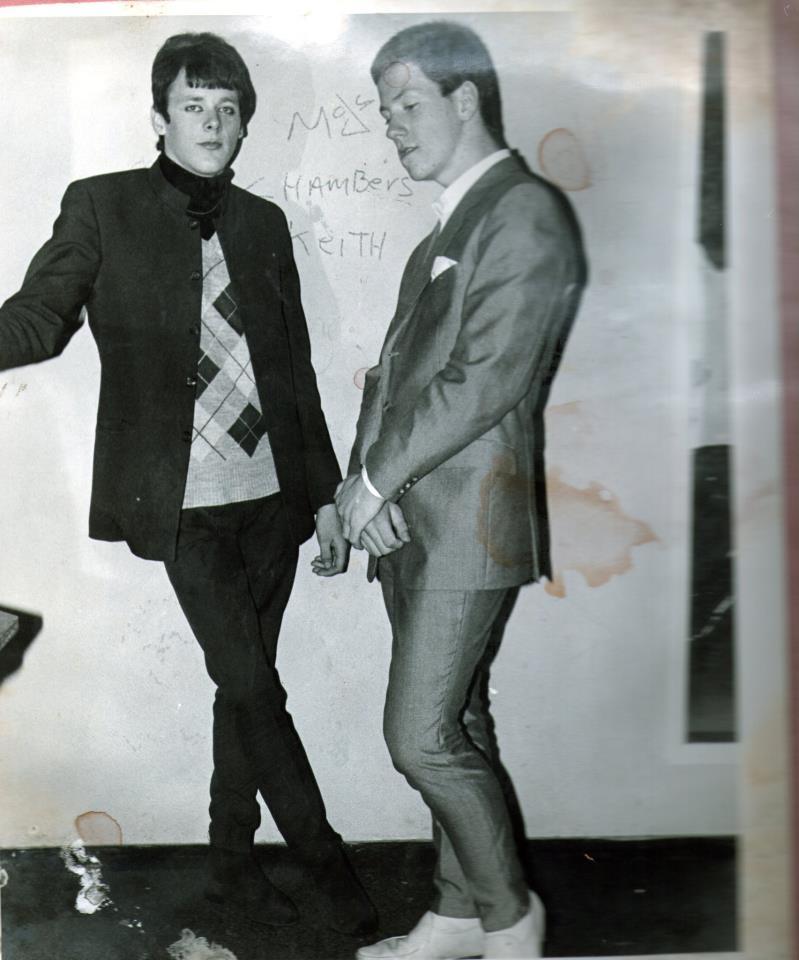

Me on the front of a book about Belfast mods

I say ‘put aside’ because putting aside such ingrained beliefs was about as much as anyone could do in those deeply divided days. You couldn’t forgive or forget, not when there was so much senseless killing happening on both sides. In my view, every outrage committed against our community had to be avenged and if I heard about IRA men killed by the Brits or the Loyalists I celebrated as happily as I’d always done.

And yet . . . .there was still the lurking knowledge that a part of my background was linked to the very community from which the IRA and its Republican offshoots came from. Allied to that, I was now one of those Mods who were mixing freely with Catholic boys and girls in the city centre, dancing the night away with them and sharing cigarettes, weed, pills, whatever, in various bars and cafes. My heart was as Protestant and Loyalist as it always had been but by now my head was telling me that under the skin, we poor sods who were stuck in the middle of a war zone were all the same. Being Belfast kids, we only needed a couple of seconds’ conversation to find out where someone was from and what religion they were but when the Mods came together this didn’t seem to matter. A person’s religion was becoming irrelevant to me , but I still hated the IRA all right.

At first I was nervous. I’d encountered Catholics before, of course, but only when I was younger. Now I was hanging around with Catholic kids who, like me, were already associating with paramilitary groups. Involvement in the UDA, UVF, IRA, INLA, etc was born of tradition. It was what you did if you came from Glencairn, Ardoyne, Shankill, Andersonstown. But when you pulled on your mohair suit – and, being newly minted I had a few of these hand-made, so I claim to be the best-dressed Mod in Belfast at the time – and fired up your Vespa, your political associations were put aside. We just didn’t talk about any of that stuff, and it was better that way.

Squire – It’s a Mod Mod World

In my childish loyalist world, I couldn’t tell the difference between ordinary peace craving Catholics and IRA killers, such lines were blurred in my childhood world. I was a product of the tribal community that I had grown up in and republicans were our sworn enemies. But the more I got to know Catholics, the less I hated them. I was no longer lumping them all into one big bunch of terrorists. The boys I was talking to as we sat astride our scooters by the City Hall, checking out each other’s suits, shirts, shoes and girlfriends, had had similar experiences to me. I knew that, and so did they. But on those precious Saturday afternoons, when we all felt young and vibrant and just happy to be alive, none of that mattered. We ignored the madness going on around us as best as we could and yet there was always the possibility of being caught up in a bomb or gun attack from Loyalist or Republican terrorists.

The Jam – A Bomb in Wardour Street

I became friendly with lots of Catholic Mods, including Bobby from the Antrim Road, who became a firm friend. I also hung out with Keith from the Westland and we spent a lot of time together. And in particular Zulu and Tom, two Mods from Ardoyne. One night they invited me up to a club they regularly frequented in their neighbourhood. Like many Loyalist and Republican clubs and bars it had a wire cage around the perimeter and doormen always on guard in case of an attack, which could happen at any time.

All my instincts told me not to go; it was in the heart of Ardoyne, the Catholic enclave bordered by Protestant West Belfast and one of the IRA’s most important heartlands. For a Prod, it couldn’t be any less dangerous. I imagined how ironic it would be if I was drinking in a Catholic area with Catholic friends and the UFF or UVF attacked the place and I was killed. My crazy side, however, ignored all that and, pilled-up and cockily confident, I fell in line behind Tom and Zulu and entered the club.

The three of us stood by the bar in our gear, chatting away ten to the dozen. After I while, I realised that a group of older men on the other side of the bar were staring at me. All the while I knew I should be winding my neck in, keeping my head down and saying very little. By now, though, I was aware I’d already said too much.

Zulu and Tom had already noticed. Tom nipped to the jakes for a pee and on the way back one of the men stopped him, looked over at me and whispered something in his ear. The smile on Tom’s face froze as he received the message.

‘See those wans over there,’ he said as he resumed his position at the bar. ‘They reckon they can tell you’re a Prod.’

‘Fuck, I knew it,’ I said. ‘They’ve been eyeballin’ me since we walked in.’

My stomach had turned to water. There was no knowing what these hard cases would do if they took a hold of me.

‘Here’s what’s gonna happen,’ said Tom. ‘You and me will slowly make your way to the back door. Zulu’ll keep these fellas talking, then go to the jakes. Then he’ll climb out the window. OK?’

I wasn’t in a position to argue. The plan went smoothly and within minutes we were out of the door and away as fast as we could. We soon realised that mixing in the city centre on a Saturday was one thing; doing the same in our neighbourhoods was asking for big trouble, and I doubt we’d have got away so easily in Glencairn or Ballysillan.

The Who – Get Out And Stay Out

But as usual I was up for anything and many times I ignored the risks involved, putting myself in real danger. Once I was at a party up the Antrim Rd and a gang of wee Provies came in, asking everyone what religion they were. I lied through my teeth and said I was a Catholic from Manor Street , which was half true as I had been living there at the time. Another night I met a very cute and sexy Mod girl who made a beeline for me and made it clear that if I were to come back to her flat we would have a very good time indeed. I didn’t need a second invitation and soon we were in a taxi, speeding through Belfast with a nice handful of pills in my coat pocket.

The Who – The Real Me

She wasn’t wrong, we had a lot of fun in her flat that night. By the time I’d dragged my head up from the pillow the following morning she’d gone off to work. I lurched into the kitchen, made myself a cup of good strong Nambarrie tea and helped myself to the rest of her loaf of bread. After an hour of mooching about I opened the curtains and looked out at the view. Immediately, a horrible realisation dawned. I was somewhere up in the Divis Tower, a grim but iconic high-rise building in the middle of the fiercely Republican Divis Flats. Many people had been killed, injured or kidnapped within the vicinity of this place, including Jean McConville, a Protestant woman who converted to Catholicism for the sake of her husband. She had ten kids, and her only crime was to help a wounded soldier. For that, she was taken away from her family and murdered by the IRA.

See: Jean McConville

Quietly, I left the flat, gently shutting the door behind me. I made my way down a series of piss-stained stairways, avoiding the strange glances of a few women going in the opposite direction. The bleakness of this place was indescribable; the houses up on Glencairn were bad enough but this was truly a horrible, dangerous and dirty dump. With as much calm as I could muster I left the estate, not looking left, right or behind me, and walked the half-mile or so towards the city centre, where I had a much-needed Ulster Fry to celebrate yet another escape from Republican West Belfast.

Even so, my associations with Catholic boys and girls were becoming ever closer. A very young Catholic boy with a huge passion for music was DJing down the Abercorn and we all got to know and respect this kid who was barely out of school. His name was David Holmes and he went on to become one of the world’s foremost DJs, producers and re-mixers. It’s amazing to think that these early experiences in the Mod clubs and cafes inspired him to become the success story he is today.

Me and David Holmes

Meanwhile, I’d gone from chatting to Catholics to actually dating them. I met a girl called Kathy who lived a couple of minutes from the Royal Victoria Hospital along the Falls Road. She was small and very pretty and from the moment we met we had great banter together. She was also a trained hairdresser and would cut my hair for nothing, which was also quite appealing. She could have been the one for me to settle down with, but I was young and had ants in my pants and didn’t want to be tied down at the time. Pills and parties were my thing, not tea and nights in front of the telly. Kathy understood this and we were both in it for the craic.

The Jam – When You’re Young