Key Events & Deaths on this day in Northern Ireland Troubles

17th May

——————————————-

Wednesday 17 May 1972

The Irish Republican Army (IRA) opened fire on workers leaving the Mackies engineering works in West Belfast.

[Although the factory was sited in a Catholic area it had an almost entirely Protestant workforce.]

Thursday 17 May 1973

The Irish Republican Army (IRA) carried out a booby-trap bomb attack on five members of the British Army who were off duty at the time. The attack occurred in Omagh, County Tyrone.

See Palace Barracks for more details

[Four soldiers were killed on the day and the fifth soldier died on 3 June 1973.]

Loyalists killed two Catholic civilians in Belfast.

The Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) shot dead a man in County Fermanagh.

Friday 17 May 1974

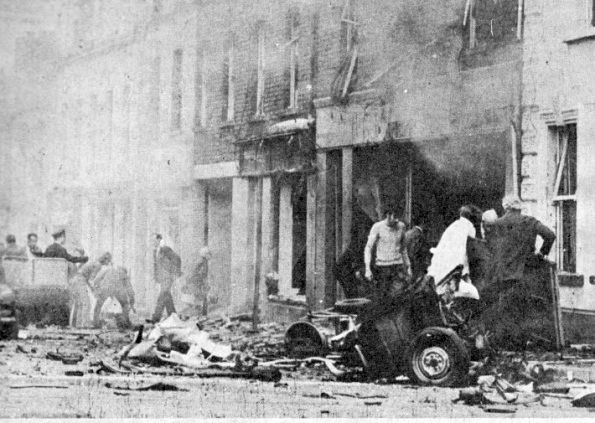

Dublin and Monaghan Bombings 33 People Killed

Day 3 of the UWC strike

33 civilians and an unborn child were killed in the Republic of Ireland as a result of a series of explosions when four car bombs were planted by Loyalist paramilitaries in Dublin and Monaghan.

Approximately 258 people were also injured in the explosions. The death toll from the bombings was the largest in any single day of the conflict. No one was ever arrested or convicted of causing the explosions.

[On 15 July 1993 the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) claimed sole responsibility for carrying out the bomb attacks.]

In Dublin three car bombs exploded, almost simultaneously at approximately 5.30pm, in Parnell Street, Talbot Street, and South Leinster Street. 23 men, women and children died in these explosions and 3 others died as a result of injuries over the following few days. Another car bomb exploded at approximately 7.00pm in North Road, Monaghan, killing 5 people initially with another 2 dying in the following weeks.

The first of the three Dublin bombs went off at approximately 5.28pm in Parnell Street. Eleven people died as a result of this explosion.

The second of the Dublin bombs went off at approximately 5.30pm in Parnell Street. Fourteen people died in this explosion. The third bomb went off at approximately 5.32pm in South Leinster Street. Two people were killed in this explosion.

News of car bombs in Dublin and Monaghan raised tensions in Northern Ireland. Sammy Smyth, then press officer of both the Ulster Defence Association (UDA) and the Ulster Workers’ Council (UWC) Strike Committee, said,

“I am very happy about the bombings in Dublin. There is a war with the Free State and now we are laughing at them.”

See Dublin and Monaghan Bombings

In Northern Ireland reductions in the supply of electricity continued to have serious consequences for industry, commerce, and the domestic sector. In addition to problems in maintaining petrol distribution, a lack of electricity also meant that pumps did not operate for substantial periods of each day. Postal delivery services came to a halt following intimidation of Royal Mail employees.

There were continuing problems in farming and in the distribution of food supplies. Special arrangements were made by the Northern Ireland Executive to ensure that payments of welfare benefits would be delivered to claimants.

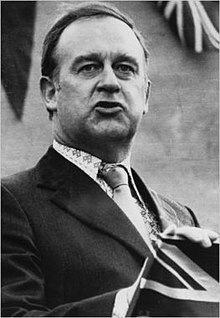

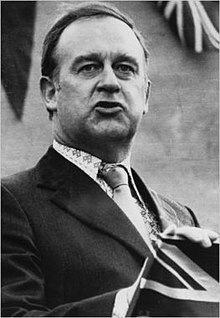

William Craig, then leader of (Ulster) Vanguard, criticised Merlyn Rees, then Secretary of Sate for Northern Ireland, for not negotiating with the Ulster Workers’ Council (UWC).

[Public Records 1974 – Released 1 January 2005: Letter from F.E.R. Butler, then in the Ministry of Defence, discussing the ‘Provision of Electric Power to Belfast’.]

Monday 17 May 1976

James Gallagher (20) was shot dead, as he travelled, as a passenger on a bus, past Fort George British Army base, Strand Road, Derry.

The soldier who shot him was on sentry duty in the base and as he handed over his rifle is reported to have said, “I’m cracking, I’m cracking”. Two other passengers on the bus, a man and a woman, were injured in the incident.

[Later Gallagher was listed on a Republican roll of honour as an Irish Republican Army (IRA) member.]

Two Protestant civilians were shot dead by Republican paramilitaries at a factory in Dungannon Street, Moy, County Tyrone.

Friday 17 May 1984

Jim Campbell, then Northern Editor of the Sunday World, was shot and seriously injured by the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) at his home in north Belfast.

See Martin Ohagan

Wednesday 17 May 1989

Local Government Elections

Local government elections were held across Northern Ireland.

[The percentage share of the vote was: Ulster Unionist Party (UUP) 31.4%; Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) 17.8%; Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP) 21.2%; Sinn Féin (SF) 11.3%; Alliance Party of Northern Ireland (APNI) 6.8%; Workers Party (WP) 2.1%; Others 9.4%; Turnout 56.0%. (See detailed results.)]

Thursday 17 May 1990

Summary of Stevens Report Published

A summary of the report of the Stevens Inquiry was published. The main finding of the report was that there had been evidence of collusion between members of the security forces and Loyalist paramilitaries.

However it was the view of the inquiry that any collusion was “restricted to a small number of members of the security forces and is neither widespread nor institutionalised”.

There was a Westminster by-election in the constituency of Upper Bann. David Trimble, of the Ulster Unionist Party (UUP), won the by-election with a majority of almost 14,000 votes. The Conservative Party candidate, Colette Jones, lost her deposit.

Sunday 17 May 1992

British soldiers of the King’s Own Scottish Borderers becamed involved in a fist-fight with local people in Coalisland, County Tyrone. Soon after members of the Parachute Regiment arrived and fired on a crowd of people standing outside a public house in the town, and shot and wounded three civilians and injured a further four others.

[This incident followed an earlier one on 12 May 1992. It was later reported that the commander of the army’s Third Brigade was transferred. Patrols by the Parachute Regiment were also ended before the official end of the regiment’s tour of duty.]

Monday 17 May 1993

The Combined Loyalist Military Command (CLMC) stated that it would look at the results of the local government elections on 19 May 1993 to see if there was any evidence of “pan-Nationalist candidates” co-operating with each other.

Tuesday 17 May 1994

Two Catholics Killed by UVF

Eamon Fox (42) and Gary Convie (24), both Catholic civilians, were shot dead by the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) at a building site on North Queen Street, in the Tiger Bay area of Belfast.

A review of the working of the Northern Ireland (Emergency Provisions) Act recommended that police interviews should be taped.

Wednesday 17 May 1995

Unemployment in Northern Ireland in April 1995 was recorded as 88,700 (11.8 per cent) the lowest it had been since December 1981

Saturday 17 May 1997

Gerry Adams, then President of Sinn Féin (SF), held a meeting with officials representing the Irish government at an undisclosed venue in Dublin. John Bruton, the Taoiseach (Irish Prime Minister), said afterwards that the meeting was to establish if the Irish Republican Army (IRA) was prepared to call a new ceasefire.

Sunday 17 May 1999

Tony Blair, then British Prime Minister, said there was no “plan B” if the Agreement was rejected in the referendum. Blair and Bill Clinton, then President of the United States of America (USA), issued a joint statement urging people to recognise the opportunities offered by the Agreement and to vote ‘Yes’.

Monday 17 May 1999

The Ulster Unionist Party (UUP) issued a blunt warning that it would not change its position on decommissioning before, during or after next month’s European election. David Trimble, then First Minister designate, challenged Tony Blair, then British Prime Minister, to state whether, in the British government’s view, devolution could proceed without the start of “actual decommissioning”.

In the Republic of Ireland 42 candidates were nominated for the European election on 11 June 1999. Fianna Fáil (FF) put forward eight candidates, Fine Gael seven, Labour five, Sinn Féin four, Natural Law Party four, and the Green Party three. For the first time there was no PD candidate.

Thursday 17 May 2001

Sean MacStiofain (73), former Chief of Staff of the (Provisional) Irish Republican Army (IRA), died in a hospital in the Republic of Ireland after a long illness. He became Chief of Staff of the Provisionals after they split from the Official IRA in 1970.

[MacStiofain had been born John Stephenson in London.]

Death

In 1993, Mac Stíofáin suffered a stroke. On 18 May 2001, he died in Our Lady’s Hospital, Navan, County Meath, after a long illness at the age of 73. He is buried in St Mary’s Cemetery, Navan.

Despite his controversial career in the IRA, many of his former comrades (and rivals) paid tribute to him after his death. Ruairí Ó Brádaigh, who attended the funeral, issued a glowing tribute, referring to Mac Stíofáin as an “outstanding IRA leader during a crucial period in Irish history” and as the “man for the job” as first Provisional IRA Chief of Staff. Gerry Adams and Martin McGuinness also attended. In her oration, Ita Ní Chionnaigh of Conradh na Gaeilge, whose flag draped the coffin, lambasted Mac Stíofáin’s “character assassination” by the “gutter press” and praised him as a man who had been “interested in the rights of men and women and people anywhere in the world who were oppressed, including Irish speakers in Ireland, who are also oppressed.

See here for more details on Sean MacStiofain

——————————————

Remembering all innocent victims of the Troubles

Today is the anniversary of the death of the following people killed as a results of the conflict in Northern Ireland

“To live in hearts we leave behind is not to die

– Thomas Campbell

To the innocent on the list – Your memory will live forever

– To the Paramilitaries –

There are many things worth living for, a few things worth dying for, but nothing worth killing for.

50 People lost their lives on the 17th between 1972 – 1990

——————————————

17 May 1972

Bernard Moane (46)

Catholic

Status: Civilian (Civ),

Killed by: Ulster Defence Association (UDA)

Found shot by Knockagh War Memorial, near Greenisland, County Antrim.

——————————————

17 May 1972

Ronald Hurst (25)

nfNI

Status: British Army (BA),

Killed by: Irish Republican Army (IRA)

Shot while working on perimeter fencing outside Crossmaglen Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) / British Army (BA) base, County Armagh.

——————————————

17 May 1973

Michael Leonard (22)

nfNI

Status: Civilian (Civ),

Killed by: Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC)

From County Donegal. Shot while driving his car, being pursued by Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) vehicle, Letter, near Pettigoe, County Fermanagh.

——————————————

17 May 1973

Eileen Mackin (14)

Catholic

Status: Civilian (Civ),

Killed by: non-specific Loyalist group (LOY)

Shot by sniper while walking along Springhill Avenue, Ballymurphy, Belfast.

——————————————

17 May 1973

Thomas Ward (34)

Catholic

Status: Civilian (Civ),

Killed by: Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF)

Shot during bomb and gun attack on Jubilee Arms, Lavinia Street, off Ormeau Road, Belfast.

——————————————

17 May 1973

Arthur Place (29)

nfNI

Status: British Army (BA),

Killed by: Irish Republican Army (IRA)

Off duty. Killed by booby trap bomb while getting into car, outside Knock-na-Moe Castle Hotel, Omagh, County Tyrone.

——————————————

17 May 1973

Derek Reed (28)

nfNI

Status: British Army (BA),

Killed by: Irish Republican Army (IRA)

Off duty. Killed by booby trap bomb while getting into car, outside Knock-na-Moe Castle Hotel, Omagh, County Tyrone.

——————————————

17 May 1973

Sheridan Young (26)

nfNI

Status: British Army (BA),

Killed by: Irish Republican Army (IRA)

Off duty. Killed by booby trap bomb while getting into car, outside Knock-na-Moe Castle Hotel, Omagh, County Tyrone. .

——————————————

17 May 1973

Barry Cox (28)

nfNI

Status: British Army (BA),

Killed by: Irish Republican Army (IRA)

Off duty. Killed by booby trap bomb while getting into car, outside Knock-na-Moe Castle Hotel, Omagh, County Tyrone.

——————————————

17 May 1973

Frederick Drake (25)

nfNI

Status: British Army (BA),

Killed by: Irish Republican Army (IRA)

Off duty. Injured by booby trap bomb while getting into car, outside Knock-na-Moe Castle Hotel, Omagh, County Tyrone. He died 3 June 1973

——————————————

Dublin and Monaghan Bombings

17 May 1974

33 People lost their lives

See Dublin and Monaghan Bombings

————————————————-

17 May 1974

Marie Butler, (21)

nfNIRI

Status: Civilian (Civ),

Killed by: Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF)

Killed when car bomb exploded Parnell Street, Dublin.

See Dublin and Monaghan Bombings

————————————————-

17 May 1974

John Dargle, (80)

nfNIRI

Status: Civilian (Civ),

Killed by: Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF)

Killed when car bomb exploded Parnell Street, Dublin.

See Dublin and Monaghan Bombings

————————————————-

17 May 1974

Patrick Fay, (47)

nfNIRI

Status: Civilian (Civ),

Killed by: Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF)

Killed when car bomb exploded Parnell Street, Dublin.

See Dublin and Monaghan Bombings

————————————————-

17 May 1974

Elizabeth Fitzgerald, (59)

nfNIRI

Status: Civilian (Civ),

Killed by: Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF)

Injured when car bomb exploded Parnell Street, Dublin. She died 19 May 1974

See Dublin and Monaghan Bombings

————————————————-

17 May 1974

Antonio Magliocco, (37)

nfNIRI

Status: Civilian (Civ),

Killed by: Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF)

Italian national. Killed when car bomb exploded Parnell Street,

See Dublin and Monaghan Bombings

————————————————-

17 May 1974

John O’Brien, (24)

nfNIRI

Status: Civilian (Civ),

Killed by: Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF)

Killed when car bomb exploded Parnell Street, Dublin.

See Dublin and Monaghan Bombings

————————————————-

17 May 1974

Anna O’Brien (22)

nfNIRI

Status: Civilian (Civ),

Killed by: Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF)

Killed when car bomb exploded Parnell Street, Dublin.

See Dublin and Monaghan Bombings

————————————————-

17 May 1974

Jacqueline O’Brien, (1)

nfNIRI

Status: Civilian (Civ),

Killed by: Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF)

Killed when car bomb exploded Parnell Street, Dublin

See Dublin and Monaghan Bombings

————————————————-

17 May 1974

Anne Marie O’Brien, (0)

nfNIRI

Status: Civilian (Civ),

Killed by: Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF)

Killed when car bomb exploded Parnell Street, Dublin.

See Dublin and Monaghan Bombings

————————————————-

17 May 1974

Edward O’Neill, (39)

nfNIRI

Status: Civilian (Civ),

Killed by: Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF)

Killed when car bomb exploded Parnell Street, Dublin.

See Dublin and Monaghan Bombings

————————————————-

17 May 1974

Breda Turner, (21)

nfNIRI

Status: Civilian (Civ),

Killed by: Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF)

Killed when car bomb exploded Parnell Street

See Dublin and Monaghan Bombings

————————————————-

17 May 1974

Anne Byrne, (35)

nfNIRI

Status: Civilian (Civ),

Killed by: Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF)

Killed when car bomb exploded Talbot Street, Dublin.

See Dublin and Monaghan Bombings

————————————————-

17 May 1974

Simone Chetrit, (30)

nfNIRI

Status: Civilian (Civ),

Killed by: Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF)

French national. Killed when car bomb exploded Talbot Street, Dublin.

See Dublin and Monaghan Bombings

————————————————-

17 May 1974

Colette Doherty, (21)

nfNIRI

Status: Civilian (Civ),

Killed by: Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF)

Killed when car bomb exploded Talbot Street, Dublin

See Dublin and Monaghan Bombings

————————————————-

17 May 1974

Breda Grace, (35)

nfNIRI

Status: Civilian (Civ)

, Killed by: Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF)

Killed when car bomb exploded Talbot Street, Dublin.

Dublin and Monagh Bombings

————————————————-

17 May 1974

Anna Marren, (20)

nfNIRI

Status: Civilian (Civ),

Killed by: Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF)

Killed when car bomb exploded Talbot Street, Dublin.

See Dublin and Monaghan Bombings

————————————————-

17 May 1974

May McKenna, (55)

nfNIRI

Status: Civilian (Civ),

Killed by: Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF)

Killed when car bomb exploded Talbot Street, Dublin.

See Dublin and Monaghan Bombings

————————————————-

17 May 1974

Dorothy Morris, (57)

nfNIRI

Status: Civilian (Civ),

Killed by: Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF)

Killed when car bomb exploded Talbot Street, Dublin.

See Dublin and Monaghan Bombings

————————————————-

17 May 1974

Marie Phelan, (20)

nfNIRI

Status: Civilian (Civ),

Killed by: Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF)

Killed when car bomb exploded Talbot Street, Dublin.

See Dublin and Monaghan Bombings

————————————————-

17 May 1974

Siobhan Roice, (19)

nfNIRI

Status: Civilian (Civ),

Killed by: Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF)

Killed when car bomb exploded Talbot Street, Dublin.

See Dublin and Monaghan Bombings

————————————————-

17 May 1974

Maureen Shields, (46)

nfNIRI

Status: Civilian (Civ),

Killed by: Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF)

Killed when car bomb exploded Talbot Street, Dublin.

See Dublin and Monaghan Bombings

————————————————-

17 May 1974

John Walshe, (27)

nfNIRI

Status: Civilian (Civ),

Killed by: Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF)

Killed when car bomb exploded Talbot Street, Dublin.

See Dublin and Monaghan Bombings

————————————————-

17 May 1974

Josephine Bradley, (21)

nfNIRI

Status: Civilian (Civ),

Killed by: Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF)

Injured when car bomb exploded Talbot Street, Dublin. She died 20 May 1974

See Dublin and Monaghan Bombings

————————————————-

17 May 1974

Concepta Dempsey, (65)

nfNIRI

Status: Civilian (Civ),

Killed by: Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF)

Injured when car bomb exploded Talbot Street, Dublin. She died 11 June 1974.

See Dublin and Monaghan Bombings

————————————————-

17 May 1974

Anna Massey, (21)

nfNIRI

Status: Civilian (Civ),

Killed by: Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF)

Killed when car bomb exploded South Leinster Street, Dublin

See Dublin and Monaghan Bombings

————————————————-

17 May 1974

Christine O’Loughlin, (51)

nfNIRI

Status: Civilian (Civ),

Killed by: Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF)

Killed when car bomb exploded South Leinster Street, Dublin.

See Dublin and Monaghan Bombings

————————————————-

17 May 1974

Patrick Askin, (44)

nfNIRI

Status: Civilian (Civ),

Killed by: Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF)

Killed when car bomb exploded Church Square, Monaghan, County Monaghan

See Dublin and Monaghan Bombings

————————————————-

17 May 1974

Thomas Campbell, (52)

nfNIRI

Status: Civilian (Civ),

Killed by: Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF)

Killed when car bomb exploded Church Square, Monaghan, County Monaghan

See Dublin and Monaghan Bombings

————————————————-

17 May 1974

John Travers, (28)

nfNIRI

Status: Civilian (Civ),

Killed by: Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF)

Killed when car bomb exploded Church Square, Monaghan, County Monaghan

See Dublin and Monaghan Bombings

————————————————-

17 May 1974

Peggy White, (45)

nfNIRI

Status: Civilian (Civ),

Killed by: Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF)

Killed when car bomb exploded Church Square, Monaghan, County Monaghan.

See Dublin and Monaghan Bombings

————————————————-

17 May 1974

George Williamson, (72)

nfNIRI

Status: Civilian (Civ),

Killed by: Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF)

Killed when car bomb exploded Church Square, Monaghan, County Monaghan

See Dublin and Monaghan Bombings

————————————————-

17 May 1974

Archie Harper, (73)

nfNIRI

Status: Civilian (Civ),

Killed by: Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF)

Injured when car bomb exploded Church Square, Monaghan, County Monaghan. He died 21 May 1974.

See Dublin and Monaghan Bombings

————————————————-

17 May 1974

Thomas Croarkin, (36)

nfNIRI

Status: Civilian (Civ),

Killed by: Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF)

Injured when car bomb exploded Church Square, Monaghan, County Monaghan. He died 24 July 1974.

See Dublin and Monaghan Bombings

————————————————-

17 May 1976

Robert Dobson (35)

Protestant

Status: Civilian (Civ),

Killed by: non-specific Republican group (REP)

Shot, together with his brother, at their business premises, Dungannon Street, Moy, County Tyrone.

——————————————

17 May 1976

Thomas Dobson (38)

Protestant

Status: Civilian (Civ),

Killed by: non-specific Republican group (REP)

Shot, together with his brother, at their business premises, Dungannon Street, Moy, County Tyrone.

——————————————

17 May 1976

James Gallagher (20)

Catholic

Status: Irish Republican Army (IRA),

Killed by: British Army (BA)

Shot while travelling on bus which was passing Fort George British Army (BA) base, Strand Road, Derry.

——————————————

17 May 1986

David Wilson (39)

Protestant

Status: Civilian (Civ),

Killed by: Irish Republican Army (IRA)

Shot while driving his firm’s van, Donaghmore, County Tyrone.

——————————————

17 May 1991

Douglas Carruthers (41)

Protestant

Status: Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC),

Killed by: Irish Republican Army (IRA)

Off duty. Killed by booby trap bomb attached to his car while driving near to his home, Mullybritt, Lisbellaw, County Fermanagh.

——————————————

17 May 1994

Eamon Fox (42)

Catholic

Status: Civilian (Civ),

Killed by: Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF)

Shot, while sitting in stationary car, at his workplace, building site, North Queen Street, Tigers Bay, Belfast.

——————————————

17 May 1994

Gary Convie (24)

Catholic

Status: Civilian (Civ),

Killed by: Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF)

Shot, while sitting in stationary car, at his workplace, building site, North Queen Street, Tigers Bay, Belfast

——————————————