The Falklands War – The Untold Story

Falklands Crisis was a 1982 war between Argentina and the United Kingdom. The conflict resulted from the long-standing dispute over the sovereignty of the Falkland Islands and South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands, which lie in the South Atlantic, east of Argentina.

The Falklands War (Spanish: Guerra de las Malvinas), also known as the Falklands Conflict, Falklands Crisis, and the Guerra del Atlántico Sur (Spanish for “South Atlantic War“), was a ten-week war between Argentina and the United Kingdom over two British overseas territories in the South Atlantic: the Falkland Islands and South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands. It began on Friday, 2 April 1982, when Argentina invaded and occupied the Falkland Islands (and, the following day, South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands) in an attempt to establish the sovereignty it had long claimed over them. On 5 April, the British government dispatched a naval task force to engage the Argentine Navy and Air Force before making an amphibious assault on the islands. The conflict lasted 74 days and ended with the Argentine surrender on 14 June 1982, returning the islands to British control. In total, 649 Argentine military personnel, 255 British military personnel, and three Falkland Islanders died during the hostilities.

The conflict was a major episode in the protracted confrontation over the territories’ sovereignty. Argentina asserted (and maintains to this day) that the islands are Argentinian territory,[6] and the Argentine government thus characterised its military action as the reclamation of its own territory. The British government regarded the action as an invasion of a territory that had been a Crown colony since 1841. Falkland Islanders, who have inhabited the islands since the early 19th century, are predominantly descendants of British settlers, and favour British sovereignty. Neither state, however, officially declared war (both sides did declare the Islands areas a war zone and officially recognised that a state of war existed between them) and hostilities were almost exclusively limited to the territories under dispute and the area of the South Atlantic where they lie.

The conflict has had a strong impact in both countries and has been the subject of various books, articles, films, and songs. Patriotic sentiment ran high in Argentina, but the outcome prompted large protests against the ruling military government, hastening its downfall. In the United Kingdom, the Conservative Party government, bolstered by the successful outcome, was re-elected the following year. The cultural and political weight of the conflict has had less effect in Britain than in Argentina, where it remains a continued topic for discussion.[7]

Relations between the United Kingdom and Argentina were restored in 1989 following a meeting in Madrid, Spain, at which the two countries’ governments issued a joint statement.[8] No change in either country’s position regarding the sovereignty of the Falkland Islands was made explicit. In 1994, Argentina’s claim to the territories was added to its constitution.[9]

Lead-up to the conflict

In the period leading up to the war – and, in particular, following the transfer of power between the military dictators General Jorge Rafael Videla and General Roberto Eduardo Viola late in March 1981 – Argentina had been in the midst of a devastating economic stagnation and large-scale civil unrest against the military junta that had been governing the country since 1976.[13] In December 1981 there was a further change in the Argentine military regime bringing to office a new junta headed by General Leopoldo Galtieri (acting president), Brigadier Basilio Lami Dozo and Admiral Jorge Anaya. Anaya was the main architect and supporter of a military solution for the long-standing claim over the islands,[14] calculating that the United Kingdom would never respond militarily.[15]

By opting for military action, the Galtieri government hoped to mobilise the long-standing patriotic feelings of Argentines towards the islands, and thus divert public attention from the country’s chronic economic problems and the regime’s ongoing human rights violations.[16] Such action would also bolster its dwindling legitimacy. The newspaper La Prensa speculated in a step-by-step plan beginning with cutting off supplies to the Islands, ending in direct actions late in 1982, if the UN talks were fruitless.[17]

The ongoing tension between the two countries over the islands increased on 19 March when a group of Argentine scrap metal merchants (actually infiltrated by Argentine marines) raised the Argentine flag at South Georgia, an act that would later be seen as the first offensive action in the war. The Royal Navy ice patrol vessel HMS Endurance was dispatched from Stanley to South Georgia in response, subsequently leading to the invasion of South Georgia by Argentine forces on 3 April. The Argentine military junta, suspecting that the UK would reinforce its South Atlantic Forces,[18] ordered the invasion of the Falkland Islands to be brought forward to 2 April.

Britain was initially taken by surprise by the Argentine attack on the South Atlantic islands, despite repeated warnings by Royal Navy captain Nicholas Barker and others. Barker believed that Defence Secretary John Nott‘s 1981 review (in which Nott described plans to withdraw the Endurance, Britain’s only naval presence in the South Atlantic) sent a signal to the Argentines that Britain was unwilling, and would soon be unable, to defend its territories and subjects in the Falklands.[19][20]

Argentine invasion

The Argentine destroyer ARA Santísima Trinidad landed Special Forces south of Stanley

On 2 April 1982, The Argentine forces mounted amphibious landings off the Falkland Islands, following the civilian occupation of South Georgia on 19 March, before the Falklands War began. The invasion was met with a nominal defence organised by the Falkland Islands’ Governor Sir Rex Hunt, giving command to Major Mike Norman of the Royal Marines. The events of the invasion included the landing of Lieutenant Commander Guillermo Sanchez-Sabarots’ Amphibious Commandos Group, the attack on Moody Brook barracks, the engagement between the troops of Hugo Santillan and Bill Trollope at Stanley, and the final engagement and surrender at Government House.

Initial British response

The cover of Newsweek magazine, 19 April 1982, depicts HMS Hermes, flagship of the British Task Force.

Word of the invasion first reached Britain from Argentine sources.[21] A Ministry of Defence operative in London had a short telex conversation with Governor Hunt’s telex operator, who confirmed that Argentines were on the island and in control.[21][22] Later that day, BBC journalist Laurie Margolis was able to speak with an islander at Goose Green via amateur radio, who confirmed the presence of a large Argentine fleet and that Argentine forces had taken control of the island.[21] Operation Corporate was the codename given to the British military operations in the Falklands War. The commander of task force operations was Admiral Sir John Fieldhouse. Operations lasted from 1 April 1982 to 20 June 1982.[23] The British undertook a series of military operations as a means of recapturing the Falklands from Argentine occupation. The British government had taken action prior to the 2 April invasion. In response to events on South Georgia, the submarines HMS Splendid and HMS Spartan were ordered to sail south on 29 March, whilst the stores ship Royal Fleet Auxiliary (RFA) Fort Austin was dispatched from the Western Mediterranean to support HMS Endurance.[24] Lord Carrington had wished to send a third submarine, but the decision was deferred due to concerns about the impact on operational commitments.[24] Coincidentally, on 26 March, the submarine HMS Superb left Gibraltar and it was assumed in the press it was heading south. There has since been speculation that the effect of those reports was to panic the Argentine junta into invading the Falklands before nuclear submarines could be deployed.[24]

The following day, during a crisis meeting headed by the Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, the Chief of the Naval Staff, Admiral Sir Henry Leach, advised them that “Britain could and should send a task force if the islands are invaded”. On 1 April, Leach sent orders to a Royal Navy force carrying out exercises in the Mediterranean to prepare to sail south. Following the invasion on 2 April, after an emergency meeting of the cabinet, approval was given to form a task force to retake the islands. This was backed in an emergency session of the House of Commons the next day.[25]

On 6 April, the British Government set up a War Cabinet to provide day-to-day political oversight of the campaign.[3] This was the critical instrument of crisis management for the British with its remit being to “keep under review political and military developments relating to the South Atlantic, and to report as necessary to the Defence and Overseas Policy Committee”. Until it was dissolved on 12 August, the War Cabinet met at least daily. Although Margaret Thatcher is described as dominating the War Cabinet, Lawrence Freedman notes in the Official History of the Falklands Campaign that she did not ignore opposition or fail to consult others. However, once a decision was reached she “did not look back”.[3]

Position of third party countries

On the evening of 3 April, the United Kingdom’s United Nations ambassador Sir Anthony Parsons put a draft resolution to the United Nations Security Council. The resolution, which condemned the hostilities and demanded the immediate Argentine withdrawal from the Islands, was adopted by the council the following day as United Nations Security Council Resolution 502, which passed with ten votes in support, one against (Panama) and four abstentions (China, the Soviet Union, Poland and Spain).[25][26][27] The UK received further political support from the Commonwealth of Nations and the European Economic Community. The EEC also provided economic support by imposing economic sanctions on Argentina. Argentina itself was politically backed by a majority of countries in Latin America and some members of the Non-Aligned Movement.[citation needed] On 20 May 1982, the Prime Minister of New Zealand, Rob Muldoon, announced that he would make HMNZS Canterbury, a Leander class frigate, available for use where the British thought fit to release a Royal Navy vessel for the Falklands.[28]

The war was an unexpected event in a world strained by the Cold War and the North–South divide. The response of some countries was the effort to mediate the crisis and later as the war began, the support (or criticism) based in terms of anti-colonialism, political solidarity, historical relationships or realpolitik.

The United States was concerned by the prospect of Argentina turning to the Soviet Union for support,[29] and initially tried to mediate an end to the conflict. However, when Argentina refused the US peace overtures, US Secretary of State Alexander Haig announced that the United States would prohibit arms sales to Argentina and provide material support for British operations. Both Houses of the US Congress passed resolutions supporting the US action siding with the United Kingdom.[30]

The US provided the United Kingdom with military equipment ranging from submarine detectors to the latest missiles.[31][32][33][34] President Ronald Reagan approved the Royal Navy’s request to borrow the Sea Harrier-capable amphibious assault ship USS Iwo Jima (LPH-2) if the British lost an aircraft carrier. The United States Navy developed a plan to help the British man the ship with American military contractors, likely retired sailors with knowledge of the Iwo Jima ’s systems.[35] France provided dissimilar aircraft training so Harrier pilots could train against the French aircraft used by Argentina.[36] French and British intelligence also worked to prevent Argentina from obtaining more Exocet missiles on the international market,[37] while at the same time Peru attempted to purchase 12 missiles for Argentina, in a failed secret operation.[38][39] Chile gave support to Britain in the form of intelligence about Argentine military and early warning radar.[40][41] Throughout the war, Argentina was afraid of a Chilean military intervention in Patagonia and kept some of her best mountain regiments away from the Falklands near the Chilean border as a precaution.[42]

In recent years, it has become known that a listening post located in Fauske, Norway was vital in giving the British intelligence information regarding Argentinian fleet locations. The listening post was designated Fauske II by Norway. The information was “stolen” from Soviet spy satellites, which were the only space assets that covered the South Atlantic.[43] Western powers such as the United States and the UK did not have their own satellite presence in this area at the time. A high ranking British military source claimed that the intelligence the British got from the Fauske II post as “Incredibly vital”:

When the war broke out, we had almost no intelligence information from this area. It was here we got help from the Norwegians, who gave us a stream of information about the Argentinian warships positions. The information came to us all the time and straight to our war headquarters at Northwood. The information was continuously updated and told us exactly where the Argentinian ships were.[43][44]

While France overtly backed the United Kingdom, a French technical team remained in Argentina throughout the war. French government sources have said that the French team was engaged in intelligence-gathering; however, it simultaneously provided direct material support to the Argentines, identifying and fixing faults in Exocet missile launchers.[45] According to the book Operation Israel, advisers from Israel Aerospace Industries were already in Argentina and continued their work during the conflict. The book also claims that Israel sold weapons and drop tanks in a secret operation in Peru.[46][47] Peru also openly sent “Mirages, pilots and missiles” to Argentina during the war.[48] Peru had earlier transferred ten Hercules transport planes to Argentina soon after the British Task Force had set sail in April 1982.[49] Nick van der Bijl records that, after the Argentine defeat at Goose Green, Venezuela and Guatemala offered to send paratroops to the Falklands.[50] Through Libya, under Muammar Gaddafi, Argentina received 20 launchers and 60 SA-7 missiles, as well as machine guns, mortars and mines; all in all, the load of four trips of two Boeing 707s of the AAF, refuelled in Recife with the knowledge and consent of the Brazilian government.[51] Some of these clandestine logistics operations were mounted by the Soviet Union.[52]

British Task Force

HMS Invincible, part of the task force. Pictured in 1990

Royal Navy Fleet Air Arm Sea Harrier FRS1. The gloss paint scheme was altered to a duller one en route south.

The British government had no contingency plan for an invasion of the islands, and the task force was rapidly put together from whatever vessels were available.[53] The nuclear submarine Conqueror set sail from France on 4 April, whilst the two aircraft carriers Invincible and Hermes, in the company of escort vessels, left Portsmouth only a day later.[25] On its return to Southampton from a world cruise on 7 April, the ocean liner SS Canberra was requisitioned and set sail two days later with 3 Commando Brigade aboard.[25] The ocean liner Queen Elizabeth 2 was also requisitioned and left Southampton on 12 May with 5th Infantry Brigade on board.[25] The whole task force eventually comprised 127 ships: 43 Royal Navy vessels, 22 Royal Fleet Auxiliary ships and 62 merchant ships.[53]

The retaking of the Falkland Islands was considered extremely difficult. The US Navy considered a successful counter-invasion by the British “…a military impossibility.”[54] Firstly, the British were significantly constrained by the disparity in deployable air cover.[55] The British had 42 aircraft (28 Sea Harriers and 14 Harrier GR.3s) available for air combat operations,[56] against approximately 122 serviceable jet fighters, of which about 50 were used as air superiority fighters and the remainder as strike aircraft, in Argentina’s air forces during the war.[57] Crucially, the British lacked AEW aircraft.

Many of the British were also concerned by the Argentine surface fleet because it possessed many of the same weapons systems and capabilities as the British fleet, specifically Exocet-equipped vessels, in addition to two Type 209 submarines.[58] For this reason, the British planned to screen their fleet with submarines. They also envisaged a naval retreat on the appearance of Argentine ships to avoid surface combat.

By mid-April, the Royal Air Force had set up the airbase of RAF Ascension Island, co-located with Wideawake Airfield (USA) on the mid-Atlantic British overseas territory of Ascension Island, including a sizeable force of Avro Vulcan B Mk 2 bombers, Handley Page Victor K Mk 2 refuelling aircraft, and McDonnell Douglas Phantom FGR Mk 2 fighters to protect them. Meanwhile, the main British naval task force arrived at Ascension to prepare for active service. A small force had already been sent south to recapture South Georgia.

Encounters began in April; the British Task Force was shadowed by Boeing 707 aircraft of the Argentine Air Force during their travel to the south.[59] Several of these flights were intercepted by Sea Harriers outside the British-imposed exclusion zone; the unarmed 707s were not attacked because diplomatic moves were still in progress and the UK had not yet decided to commit itself to armed force. On 23 April, a Brazilian commercial Douglas DC-10 from VARIG Airlines en route to South Africa was intercepted by British Harriers who visually identified the civilian plane.[60]

Recapture of South Georgia and the attack on Santa Fe

The South Georgia force, Operation Paraquet, under the command of Major Guy Sheridan RM, consisted of Marines from 42 Commando, a troop of the Special Air Service (SAS) and Special Boat Service (SBS) troops who were intended to land as reconnaissance forces for an invasion by the Royal Marines. All were embarked on RFA Tidespring. First to arrive was the Churchill-class submarine HMS Conqueror on 19 April, and the island was over-flown by a radar-mapping Handley Page Victor on 20 April.

The first landings of SAS troops took place on 21 April, but—with the southern hemisphere autumn setting in—the weather was so bad that their landings and others made the next day were all withdrawn after two helicopters crashed in fog on Fortuna Glacier. On 23 April, a submarine alert was sounded and operations were halted, with Tidespring being withdrawn to deeper water to avoid interception. On 24 April, the British forces regrouped and headed in to attack.

The ARA Santa Fe sailing on the surface.

On 25 April, after resupplying the Argentine garrison in South Georgia, the submarine ARA Santa Fe was spotted on the surface[61] by a Westland Wessex HAS Mk 3 helicopter from HMS Antrim, which attacked the Argentine submarine with depth charges. HMS Plymouth launched a Westland Wasp HAS.Mk.1 helicopter, and HMS Brilliant launched a Westland Lynx HAS Mk 2. The Lynx launched a torpedo, and strafed the submarine with its pintle-mounted general purpose machine gun; the Wessex also fired on Santa Fe with its GPMG. The Wasp from HMS Plymouth as well as two other Wasps launched from HMS Endurance fired AS-12 ASM antiship missiles at the submarine, scoring hits. Santa Fe was damaged badly enough to prevent her from diving. The crew abandoned the submarine at the jetty at King Edward Point on South Georgia.

With Tidespring now far out to sea, and the Argentine forces augmented by the submarine’s crew, Major Sheridan decided to gather the 76 men he had and make a direct assault that day. After a short forced march by the British troops and a naval bombardment demonstration by two Royal Navy vessels (Antrim and Plymouth), the Argentine forces surrendered without resistance. The message sent from the naval force at South Georgia to London was, “Be pleased to inform Her Majesty that the White Ensign flies alongside the Union Jack in South Georgia. God Save the Queen.” The Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher, broke the news to the media, telling them to “Just rejoice at that news, and congratulate our forces and the Marines!”[62]

Black Buck raids

RAF Avro Vulcan B.Mk.2 strategic bomber

On 1 May, British operations on the Falklands opened with the “Black Buck 1” attack (of a series of five) on the airfield at Stanley. A Vulcan bomber from Ascension flew on an 8,000-nautical-mile (15,000 km; 9,200 mi) round trip dropping conventional bombs across the runway at Stanley and back to Ascension. The mission required repeated refuelling, and required several Victor tanker aircraft operating in concert, including tanker to tanker refuelling. The overall effect of the raids on the war is difficult to determine, and the raids consumed precious tanker resources from Ascension,[63] but also prevented Argentina from stationing fast jets on the islands.

The raids did minimal damage to the runway, and damage to radars was quickly repaired. As of 2014[update] the Royal Air Force Web site still states that all the three bombing missions had been successful,[64] but historian Lawrence Freedman, who had access to classified documents, said in a 2005 book that the subsequent bombing missions were failures.[65] Argentine sources said that the Vulcan raids influenced Argentina to withdraw some of its Mirage IIIs from Southern Argentina to the Buenos Aires Defence Zone.[66][67][68] This was later described as propaganda by Falklands veteran Commander Nigel Ward.[69] In any case, the effect of the Vulcan raids on Argentina’s deployment of defensive fighters was watered down when British officials made clear that there would be no strikes on air bases in Argentina.[70]

Of the five Black Buck raids, three were against Stanley Airfield, with the other two anti-radar missions using Shrike anti-radiation missiles.

Escalation of the air war

French-built Super Étendard of the Argentine Naval Aviation

The Falklands had only three airfields. The longest and only paved runway was at the capital, Stanley, and even that was too short to support fast jets (although an arrestor gear was fitted in April to support Skyhawks). Therefore, the Argentines were forced to launch their major strikes from the mainland, severely hampering their efforts at forward staging, combat air patrols and close air support over the islands. The effective loiter time of incoming Argentine aircraft was low, and they were later compelled to overfly British forces in any attempt to attack the islands.

The first major Argentine strike force comprised 36 aircraft (A-4 Skyhawks, IAI Daggers, English Electric Canberras, and Mirage III escorts), and was sent on 1 May, in the belief that the British invasion was imminent or landings had already taken place. Only a section of Grupo 6 (flying IAI Dagger aircraft) found ships, which were firing at Argentine defences near the islands. The Daggers managed to attack the ships and return safely. This greatly boosted morale of the Argentine pilots, who now knew they could survive an attack against modern warships, protected by radar ground clutter from the Islands and by using a late pop up profile. Meanwhile, other Argentine aircraft were intercepted by BAE Sea Harriers operating from HMS Invincible. A Dagger[71] and a Canberra were shot down.

Combat broke out between Sea Harrier FRS Mk 1 fighters of No. 801 Naval Air Squadron and Mirage III fighters of Grupo 8. Both sides refused to fight at the other’s best altitude, until two Mirages finally descended to engage. One was shot down by an AIM-9L Sidewinder air-to-air missile (AAM), while the other escaped but was damaged and without enough fuel to return to its mainland air base. The plane made for Stanley, where it fell victim to friendly fire from the Argentine defenders.[72]

As a result of this experience, Argentine Air Force staff decided to employ A-4 Skyhawks and Daggers only as strike units, the Canberras only during the night, and Mirage IIIs (without air refuelling capability or any capable AAM) as decoys to lure away the British Sea Harriers. The decoying would be later extended with the formation of the Escuadrón Fénix, a squadron of civilian jets flying 24 hours-a-day simulating strike aircraft preparing to attack the fleet. On one of these flights, an Air Force Learjet was shot down, killing the squadron commander, Vice Commodore Rodolfo De La Colina, the highest-ranking Argentine officer to die in the war.[73][74] Stanley was used as an Argentine strongpoint throughout the conflict. Despite the Black Buck and Harrier raids on Stanley airfield (no fast jets were stationed there for air defence) and overnight shelling by detached ships, it was never out of action entirely. Stanley was defended by a mixture of surface-to-air missile (SAM) systems (Franco-German Roland and British Tigercat) and Swiss-built Oerlikon 35 mm twin anti-aircraft cannons. Lockheed Hercules transport night flights brought supplies, weapons, vehicles, and fuel, and airlifted out the wounded up until the end of the conflict.

The only Argentine Hercules shot down by the British was lost on 1 June when TC-63 was intercepted by a Sea Harrier in daylight[75][76] when it was searching for the British fleet north-east of the islands after the Argentine Navy retired its last SP-2H Neptune due to airframe attrition.

Various options to attack the home base of the five Argentine Etendards at Río Grande were examined and discounted (Operation Mikado), subsequently five Royal Navy submarines lined up, submerged, on the edge of Argentina’s 12-nautical-mile (22 km; 14 mi) territorial limit to provide early warning of bombing raids on the British task force.[77]

Sinking of ARA General Belgrano

Two British naval task forces (one of surface vessels and one of submarines) and the Argentine fleet were operating in the neighbourhood of the Falklands and soon came into conflict. The first naval loss was the World War II-vintage Argentine light cruiser ARA General Belgrano. The nuclear-powered submarine HMS Conqueror sank General Belgrano on 2 May. Three hundred and twenty-three members of General Belgrano ’s crew died in the incident. Over 700 men were rescued from the open ocean despite cold seas and stormy weather. The losses from General Belgrano totalled nearly half of the Argentine deaths in the Falklands conflict and the loss of the ship hardened the stance of the Argentine government.

Regardless of controversies over the sinking, due to disagreement on the exact nature of the Maritime Exclusion Zone and whether General Belgrano had been returning to port at the time of the sinking, it had a crucial strategic effect: the elimination of the Argentine naval threat. After her loss, the entire Argentine fleet, with the exception of the conventional submarine ARA San Luis,[61] returned to port and did not leave again during the fighting. The two escorting destroyers and the battle group centred on the aircraft carrier ARA Veinticinco de Mayo both withdrew from the area, ending the direct threat to the British fleet that their pincer movement had represented.

In a separate incident later that night, British forces engaged an Argentine patrol gunboat, the ARA Alferez Sobral, that was searching for the crew of the Argentine Air Force Canberra light bomber shot down on 1 May. Two Royal Navy Lynx helicopters fired four Sea Skua missiles at her. Badly damaged and with eight crew dead, Alferez Sobral managed to return to Puerto Deseado two days later. The Canberra’s crew were never found.

Sinking of HMS Sheffield

On 4 May, two days after the sinking of Belgrano, the British lost the Type 42 destroyer HMS Sheffield to fire following an Exocet missile strike from the Argentine 2nd Naval Air Fighter/Attack Squadron. Sheffield had been ordered forward with two other Type 42s to provide a long-range radar and medium-high altitude missile picket far from the British carriers. She was struck amidships, with devastating effect, ultimately killing 20 crew members and severely injuring 24 others. The ship was abandoned several hours later, gutted and deformed by the fires that continued to burn for six more days. She finally sank outside the Maritime Exclusion Zone on 10 May.

The incident is described in detail by Admiral Sandy Woodward in his book One Hundred Days, Chapter One. Woodward was a former commanding officer of Sheffield.[78]

The tempo of operations increased throughout the second half of May as the United Nations’ attempts to mediate a peace were rejected by the British, who felt that any delay would make a campaign impractical in the South Atlantic storms. The destruction of Sheffield (the first Royal Navy ship sunk in action since World War II) had a profound impact on the British public, bringing home the fact that the “Falklands Crisis”, as the BBC News put it, was now an actual “shooting war”.

British special forces operations

Given the threat to the British fleet posed by the Etendard-Exocet combination, plans were made to use C-130s to fly in some SAS troops to attack the home base of the five Etendards at Río Grande, Tierra del Fuego. The operation was codenamed “Mikado“. The operation was later scrapped, after acknowledging that its chances of success were limited, and replaced with a plan to use HMS Onyx to drop SAS operatives several miles offshore at night for them to make their way to the coast aboard rubber inflatables and proceed to destroy Argentina’s remaining Exocet stockpile.[79]

An SAS reconnaissance team was dispatched to carry out preparations for a seaborne infiltration. A Westland Sea King helicopter carrying the assigned team took off from HMS Invincible on the night of 17 May, but bad weather forced it to land 50 miles (80 km) from its target and the mission was aborted.[80] The pilot flew to Chile, landed south of Punta Arenas, and dropped off the SAS team. The helicopter’s crew of three then destroyed the aircraft, surrendered to Chilean police on 25 May, and were repatriated to the UK after interrogation. The discovery of the burnt-out helicopter attracted considerable international attention. Meanwhile, the SAS team crossed and penetrated deep into Argentina, but cancelled their mission after the Argentines suspected an SAS operation and deployed some 2,000 troops to search for them. The SAS men were able to return to Chile, and took a civilian flight back to the UK.[81]

On 14 May the SAS carried out a raid on Pebble Island on the Falklands, where the Argentine Navy had taken over a grass airstrip map for FMA IA 58 Pucará light ground-attack aircraft and Beechcraft T-34 Mentors, which resulted with the destruction of several aircraft.[nb 4]

Land battles

Landing at San Carlos—Bomb Alley

British sailors in anti-flash gear at action stations on HMS Cardiff near San Carlos, June 1982.

During the night of 21 May, the British Amphibious Task Group under the command of Commodore Michael Clapp (Commodore, Amphibious Warfare – COMAW) mounted Operation Sutton, the amphibious landing on beaches around San Carlos Water,[nb 5] on the northwestern coast of East Falkland facing onto Falkland Sound. The bay, known as Bomb Alley by British forces, was the scene of repeated air attacks by low-flying Argentine jets.[82][83]

The 4,000 men of 3 Commando Brigade were put ashore as follows: 2nd Battalion, Parachute Regiment (2 Para) from the RORO ferry Norland and 40 Commando Royal Marines from the amphibious ship HMS Fearless were landed at San Carlos (Blue Beach), 3rd Battalion, Parachute Regiment (3 Para) from the amphibious ship HMS Intrepid was landed at Port San Carlos (Green Beach) and 45 Commando from RFA Stromness was landed at Ajax Bay (Red Beach). Notably, the waves of eight LCUs and eight LCVPs were led by Major Ewen Southby-Tailyour, who had commanded the Falklands detachment NP8901 from March 1978 to 1979. 42 Commando on the ocean liner SS Canberra was a tactical reserve. Units from the Royal Artillery, Royal Engineers, etc. and armoured reconnaissance vehicles were also put ashore with the landing craft, the Round table class LSL and mexeflote barges. Rapier missile launchers were carried as underslung loads of Sea Kings for rapid deployment.

By dawn the next day, they had established a secure beachhead from which to conduct offensive operations. From there, Brigadier Julian Thompson‘s plan was to capture Darwin and Goose Green before turning towards Port Stanley. Now, with the British troops on the ground, the Argentine Air Force began the night bombing campaign against them using Canberra bomber planes until the last day of the war (14 June).

HMS Antelope smoking after being hit, 23 May

At sea, the paucity of the British ships’ anti-aircraft defences was demonstrated in the sinking of HMS Ardent on 21 May, HMS Antelope on 24 May, and MV Atlantic Conveyor (struck by two AM39 Exocets) on 25 May along with a vital cargo of helicopters, runway-building equipment and tents. The loss of all but one of the Chinook helicopters being carried by the Atlantic Conveyor was a severe blow from a logistical perspective.

Also lost on this day was HMS Coventry, a sister to Sheffield, whilst in company with HMS Broadsword after being ordered to act as a decoy to draw away Argentine aircraft from other ships at San Carlos Bay.[84] HMS Argonaut and HMS Brilliant were badly damaged. However, many British ships escaped being sunk because of weaknesses of the Argentine pilots’ bombing tactics described below.

To avoid the highest concentration of British air defences, Argentine pilots released ordnance from very low altitude, and hence their bomb fuzes did not have sufficient time to arm before impact. The low release of the retarded bombs (some of which the British had sold to the Argentines years earlier) meant that many never exploded, as there was insufficient time in the air for them to arm themselves. A simple free-fall bomb in a low altitude release, impacts almost directly below the aircraft, which is then within the lethal fragmentation zone of the explosion.

A retarded bomb has a small parachute or air brake that opens to reduce the speed of the bomb to produce a safe horizontal separation between the two. The fuze for a retarded bomb requires that the retarder be open a minimum time to ensure safe separation. The pilots would have been aware of this—but due to the high concentration required to avoid SAMs, Anti-Aircraft Artillery (AAA), and British Sea Harriers, many failed to climb to the necessary release point. The Argentinian forces solved the problem by fitting improvised retarding devices, allowing the pilots to effectively employ low-level bombing attacks on 8 June.

In his autobiographical account of the Falklands War, Admiral Woodward blamed the BBC World Service for disclosing information that led the Argentines to change the retarding devices on the bombs. The World Service reported the lack of detonations after receiving a briefing on the matter from a Ministry of Defence official. He describes the BBC as being more concerned with being “fearless seekers after truth” than with the lives of British servicemen.[85] Colonel ‘H’. Jones levelled similar accusations against the BBC after they disclosed the impending British attack on Goose Green by 2 Para.

Thirteen bombs hit British ships without detonating.[86] Lord Craig, the retired Marshal of the Royal Air Force, is said to have remarked: “Six better fuses and we would have lost”[87] although Ardent and Antelope were both lost despite the failure of bombs to explode. The fuzes were functioning correctly, and the bombs were simply released from too low an altitude.[85] [88] The Argentines lost 22 aircraft in the attacks.[nb 6]

Battle of Goose Green

From early on 27 May until 28 May, 2 Para, (approximately 500 men) with artillery support from 8 (Alma) Commando Battery, Royal Artillery, approached and attacked Darwin and Goose Green, which was held by the Argentine 12th Infantry Regiment. After a tough struggle that lasted all night and into the next day, the British won the battle; in all, 17 British and 47 Argentine soldiers were killed. In total 961 Argentine troops (including 202 Argentine Air Force personnel of the Condor airfield) were taken prisoner.

The BBC announced the taking of Goose Green on the BBC World Service before it had actually happened. It was during this attack that Lieutenant Colonel H. Jones, the commanding officer of 2 Para, was killed at the head of his battalion while charging into the well-prepared Argentine positions. He was posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross.

With the sizeable Argentine force at Goose Green out of the way, British forces were now able to break out of the San Carlos beachhead. On 27 May, men of 45 Cdo and 3 Para started a loaded march across East Falkland towards the coastal settlement of Teal Inlet.

Special forces on Mount Kent

Meanwhile, 42 Commando prepared to move by helicopter to Mount Kent.[nb 7] Unknown to senior British officers, the Argentine generals were determined to tie down the British troops in the Mount Kent area, and on 27 and 28 May they sent transport aircraft loaded with Blowpipe surface-to-air missiles and commandos (602nd Commando Company and 601st National Gendarmerie Special Forces Squadron) to Stanley. This operation was known as Operation AUTOIMPUESTA (Self-Determination-Initiative).

For the next week, the SAS and the Mountain and Arctic Warfare Cadre (M&AWC) of 3 Commando Brigade waged intense patrol battles with patrols of the volunteers’ 602nd Commando Company under Major Aldo Rico, normally 2nd in Command of the 22nd Mountain Infantry Regiment. Throughout 30 May, Royal Air Force Harriers were active over Mount Kent. One of them, Harrier XZ963, flown by Squadron Leader Jerry Pook—in responding to a call for help from D Squadron, attacked Mount Kent’s eastern lower slopes, and that led to its loss through small-arms fire. Pook was subsequently awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross.[89]

The Argentine Navy used their last AM39 Exocet missile attempting to attack HMS Invincible on 30 May. There are Argentine claims that the missile struck;[90][91] however, the British have denied this, some citing that HMS Avenger shot it down.[92][93] When Invincible returned to the UK after the war, she showed no signs of missile damage.

On 31 May, the M&AWC defeated Argentine Special Forces at the Battle of Top Malo House. A 13-strong Argentine Army Commando detachment (Captain José Vercesi’s 1st Assault Section, 602nd Commando Company) found itself trapped in a small shepherd’s house at Top Malo. The Argentine commandos fired from windows and doorways and then took refuge in a stream bed 200 metres (700 ft) from the burning house. Completely surrounded, they fought 19 M&AWC marines under Captain Rod Boswell for 45 minutes until, with their ammunition almost exhausted, they elected to surrender.

Three Cadre members were badly wounded. On the Argentine side, there were two dead, including Lieutenant Ernesto Espinoza and Sergeant Mateo Sbert (who were decorated for their bravery). Only five Argentines were left unscathed. As the British mopped up Top Malo House, Lieutenant Fraser Haddow’s M&AWC patrol came down from Malo Hill, brandishing a large Union Flag. One wounded Argentine soldier, Lieutenant Horacio Losito, commented that their escape route would have taken them through Haddow’s position.

601st Commando tried to move forward to rescue 602nd Commando Company on Estancia Mountain. Spotted by 42 Commando, they were engaged with 81mm mortars and forced to withdraw to Two Sisters mountain. The leader of 602nd Commando Company on Estancia Mountain realised his position had become untenable and after conferring with fellow officers ordered a withdrawal.[94]

The Argentine operation also saw the extensive use of helicopter support to position and extract patrols; the 601st Combat Aviation Battalion also suffered casualties. At about 11.00 am on 30 May, an Aerospatiale SA-330 Puma helicopter was brought down by a shoulder-launched Stinger surface-to-air missile (SAM) fired by the SAS in the vicinity of Mount Kent. Six National Gendarmerie Special Forces were killed and eight more wounded in the crash.[95]

As Brigadier Thompson commented, “It was fortunate that I had ignored the views expressed by Northwood HQ that reconnaissance of Mount Kent before insertion of 42 Commando was superfluous. Had D Squadron not been there, the Argentine Special Forces would have caught the Commando before de-planing and, in the darkness and confusion on a strange landing zone, inflicted heavy casualties on men and helicopters.”[96]

Bluff Cove and Fitzroy

By 1 June, with the arrival of a further 5,000 British troops of the 5th Infantry Brigade, the new British divisional commander, Major General Jeremy Moore RM, had sufficient force to start planning an offensive against Stanley. During this build-up, the Argentine air assaults on the British naval forces continued, killing 56. Of the dead, 32 were from the Welsh Guards on RFA Sir Galahad and RFA Sir Tristram on 8 June. According to Surgeon-Commander Rick Jolly of the Falklands Field Hospital, more than 150 men suffered burns and injuries of some kind in the attack, including, famously, Simon Weston.[97]

The Guards were sent to support an advance along the southern approach to Stanley. On 2 June, a small advance party of 2 Para moved to Swan Inlet house in a number of Army Westland Scout helicopters. Telephoning ahead to Fitzroy, they discovered that the area was clear of Argentines and (exceeding their authority) commandeered the one remaining RAF Chinook helicopter to frantically ferry another contingent of 2 Para ahead to Fitzroy (a settlement on Port Pleasant) and Bluff Cove (a settlement on Port Fitzroy).

This uncoordinated advance caused great difficulties in planning for the commanders of the combined operation, as they now found themselves with a 30 miles (48 km) string of indefensible positions on their southern flank. Support could not be sent by air as the single remaining Chinook was already heavily oversubscribed. The soldiers could march, but their equipment and heavy supplies would need to be ferried by sea.

Plans were drawn up for half the Welsh Guards to march light on the night of 2 June, whilst the Scots Guards and the second half of the Welsh Guards were to be ferried from San Carlos Water in the Landing Ship Logistics (LSL) Sir Tristram and the landing platform dock (LPD) Intrepid on the night of 5 June. Intrepid was planned to stay one day and unload itself and as much of Sir Tristram as possible, leaving the next evening for the relative safety of San Carlos. Escorts would be provided for this day, after which Sir Tristram would be left to unload using a Mexeflote (a powered raft) for as long as it took to finish.

Political pressure from above to not risk the LPD forced Commodore Clapp to alter this plan. Two lower-value LSLs would be sent, but with no suitable beaches to land on, Intrepid’s landing craft would need to accompany them to unload. A complicated operation across several nights with Intrepid and her sister ship Fearless sailing half-way to dispatch their craft was devised.

The attempted overland march by half the Welsh Guards failed, possibly as they refused to march light and attempted to carry their equipment. They returned to San Carlos and landed directly at Bluff Cove when Fearless dispatched her landing craft. Sir Tristram sailed on the night of 6 June and was joined by Sir Galahad at dawn on 7 June. Anchored 1,200 feet (370 m) apart in Port Pleasant, the landing ships were near Fitzroy, the designated landing point.

The landing craft should have been able to unload the ships to that point relatively quickly, but confusion over the ordered disembarcation point (the first half of the Guards going direct to Bluff Cove) resulted in the senior Welsh Guards infantry officer aboard insisting that his troops should be ferried the far longer distance directly to Port Fitzroy/Bluff Cove. The alternative was for the infantrymen to march via the recently repaired Bluff Cove bridge (destroyed by retreating Argentine combat engineers) to their destination, a journey of around seven miles (11 km).

On Sir Galahad ’s stern ramp there was an argument about what to do. The officers on board were told that they could not sail to Bluff Cove that day. They were told that they had to get their men off ship and onto the beach as soon as possible as the ships were vulnerable to enemy aircraft. It would take 20 minutes to transport the men to shore using the LCU and Mexeflote. They would then have the choice of walking the seven miles to Bluff Cove or wait until dark to sail there. The officers on board said that they would remain on board until dark and then sail. They refused to take their men off the ship. They possibly doubted that the bridge had been repaired due to the presence on board Sir Galahad of the Royal Engineer Troop whose job it was to repair the bridge. The Welsh Guards were keen to rejoin the rest of their Battalion, who were potentially facing the enemy without their support. They had also not seen any enemy aircraft since landing at San Carlos and may have been overconfident in the air defences. Ewen Southby-Tailyour gave a direct order for the men to leave the ship and go to the beach. The order was ignored.

The longer journey time of the landing craft taking the troops directly to Bluff Cove and the squabbling over how the landing was to be performed caused an enormous delay in unloading. This had disastrous consequences. Without escorts, having not yet established their air defence, and still almost fully laden, the two LSLs in Port Pleasant were sitting targets for two waves of Argentine A-4 Skyhawks.

The disaster at Port Pleasant (although often known as Bluff Cove) would provide the world with some of the most sobering images of the war as TV news video footage showed Navy helicopters hovering in thick smoke to winch survivors from the burning landing ships.

British casualties were 48 killed and 115 wounded.[98] Three Argentine pilots were also killed. The air strike delayed the scheduled British ground attack on Stanley by two days.[99] However, Argentine General Mario Menendez, commander of Argentine forces in the Falklands, was told that 900 British soldiers had died. He expected that the losses would cause enemy morale to drop and the British assault to stall.

Fall of Stanley

On the night of 11 June, after several days of painstaking reconnaissance and logistic build-up, British forces launched a brigade-sized night attack against the heavily defended ring of high ground surrounding Stanley. Units of 3 Commando Brigade, supported by naval gunfire from several Royal Navy ships, simultaneously attacked in the Battle of Mount Harriet, Battle of Two Sisters, and Battle of Mount Longdon. Mount Harriet was taken at a cost of 2 British and 18 Argentine soldiers. At Two Sisters, the British faced both enemy resistance and friendly fire, but managed to capture their objectives. The toughest battle was at Mount Longdon. British forces were bogged down by assault rifle, mortar, machine gun, artillery fire, sniper fire, and ambushes. Despite this, the British continued their advance.

During this battle, 13 were killed when HMS Glamorgan, straying too close to shore while returning from the gun line, was struck by an improvised trailer-based Exocet MM38 launcher taken from the destroyer ARA Seguí by Argentine Navy technicians.[100] On the same day, Sergeant Ian McKay of 4 Platoon, B Company, 3 Para died in a grenade attack on an Argentine bunker, which earned him a posthumous Victoria Cross. After a night of fierce fighting, all objectives were secured. Both sides suffered heavy losses.

The night of 13 June saw the start of the second phase of attacks, in which the momentum of the initial assault was maintained. 2 Para, with CVRT support from The Blues and Royals, captured Wireless Ridge at the Battle of Wireless Ridge, with the loss of 3 British and 25 Argentine lives, and the 2nd battalion, Scots Guards captured Mount Tumbledown at the Battle of Mount Tumbledown, which cost 10 British and 30 Argentine lives.

With the last natural defence line at Mount Tumbledown breached, the Argentine town defences of Stanley began to falter. In the morning gloom, one company commander got lost and his junior officers became despondent. Private Santiago Carrizo of the 3rd Regiment described how a platoon commander ordered them to take up positions in the houses and “if a Kelper resists, shoot him”, but the entire company did nothing of the kind.[101]

A ceasefire was declared on 14 June and the commander of the Argentine garrison in Stanley, Brigade General Mario Menéndez, surrendered to Major General Jeremy Moore the same day.

Recapture of South Sandwich Islands

On 20 June, the British retook the South Sandwich Islands (which involved accepting the surrender of the Southern Thule Garrison at the Corbeta Uruguay base), and declared hostilities over. Argentina had established Corbeta Uruguay in 1976, but prior to 1982 the United Kingdom had contested the existence of the Argentine base only through diplomatic channels.

Casualties

In total 907 were killed during the 74 days of the conflict:

- Argentina – 649[102]

- Ejército Argentino (Army) – 194 (16 officers, 35 Non-commissioned officers (NCO) and 143 conscript privates)[103]

- Armada de la República Argentina (Navy) – 341 (including 321 in Belgrano and 4 naval aviators)

- Fuerza Aérea Argentina (Air Force) – 55 (including 31 pilots and 14 ground crew)[105]

- Gendarmería Nacional Argentina (Border Guard) – 7

- Prefectura Naval Argentina (Coast Guard) – 2

- Civilian sailors – 16

- United Kingdom – A total of 255 British servicemen and 3 female Falkland Island civilians were killed during the Falklands War.[106]

- Royal Navy – 86 + 2 Hong Kong laundrymen (see below)[107]

- Royal Marines – 27 (2 officers, 14 NCOs and 11 marines)[108]

- Royal Fleet Auxiliary – 4 + 6 Hong Kong sailors[109][110]

- Merchant Navy – 6[109]

- British Army – 123 (7 officers, 40 NCOs and 76 privates)[111][112][113]

- Royal Air Force – 1 (1 officer)[109]

- Falkland Islands civilians – 3 women killed by friendly fire[109]

Of the 86 Royal Navy personnel, 22 were lost in HMS Ardent, 19 + 1 lost in HMS Sheffield, 19 + 1 lost in HMS Coventry and 13 lost in HMS Glamorgan. Fourteen naval cooks were among the dead, the largest number from any one branch in the Royal Navy.

Thirty-three of the British Army’s dead came from the Welsh Guards, 21 from the 3rd Battalion, the Parachute Regiment, 18 from the 2nd Battalion, the Parachute Regiment, 19 from the Special Air Service, 3 from Royal Signals and 8 from each of the Scots Guards and Royal Engineers. The 1st battalion/7th Duke of Edinburgh’s Own Gurkha Rifles lost one man killed.

Two more British deaths may be attributed to Operation Corporate, bringing the total to 260:

- Captain Brian Biddick from SS Uganda underwent an emergency operation on the voyage to the Falklands. Later he was repatriated by an RAF medical flight to the hospital at Wroughton where he died on 12 May.[114]

- Paul Mills from HMS Coventry suffered from complications from a skull fracture sustained in the sinking of his ship and died on 29 March 1983; he is buried in his home town of Swavesey.[115]

There were 1,188 Argentine and 777 British non-fatal casualties.

Further information about the field hospitals and hospital ships is at Ajax Bay and List of hospitals and hospital ships of the Royal Navy. On the Argentine side beside the Military Hospital at Port Stanley, the Argentine Air Force Mobile Field Hospital was deployed at Comodoro Rivadavia.

Red Cross Box[edit]

| This section does not cite any references or sources. (February 2014) |

Before British offensive operations began, the British and Argentine governments agreed to establish an area on the high seas where both sides could station hospital ships without fear of attack by the other side. This area, a circle 20 nautical miles in diameter, was referred to as the Red Cross Box (

48°30′S 53°45′W / 48.500°S 53.750°W / -48.500; -53.750), about 45 miles (72 km) north of Falkland Sound). Ultimately, the British stationed four ships (HMS Hydra, HMS Hecla and HMS Herald and the primary hospital ship Uganda) within the box, while the Argentinians stationed three (Almirante Irizar, Bahia Paraiso and Puerto Deseado).

The hospital ships were non-warships converted to serve as hospital ships. The three British naval vessels were survey vessels and Uganda was a passenger liner. Almirante Irizar was an icebreaker, Bahia Paraiso was an Antarctic supply transport and Puerto Deseado was a survey ship. The British and Argentine vessels operating within the Box were in radio contact and there was some transfer of patients between the hospital ships. For example, the British hospital ship SS Uganda on four occasions transferred patients to an Argentinian hospital ship. The British naval hospital ships operated as casualty ferries, carrying casualties from both sides from the Falklands to Uganda and operating a shuttle service between the Red Cross Box and Montevideo.

Throughout the conflict officials of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) conducted inspections to verify that all concerned were abiding by the rules of the Geneva Convention. On 12 June, some personnel transferred from the Argentine hospital ship to the British ships by helicopter. Argentine naval officers also inspected the British casualty ferries in the estuary of the River Plate.

British casualty evacuation

Hydra worked with Hecla and Herald, to take casualties from Uganda to Montevideo, Uruguay, where a fleet of Uruguayan ambulances would meet them. RAF VC10 aircraft then flew the casualties to the UK for transfer to the Princess Alexandra Royal Air Force Hospital at RAF Wroughton, near Swindon.[citation needed]

Aftermath

This brief war brought many consequences for all the parties involved, besides the considerable casualty rate and large materiel loss, especially of shipping and aircraft, relative to the deployed military strengths of the opposing sides.

In the United Kingdom, Margaret Thatcher’s popularity increased. The success of the Falklands campaign was widely regarded as the factor in the turnaround in fortunes for the Conservative government, who had been trailing behind the SDP-Liberal Alliance in the opinion polls for months before the conflict began, but after the success in the Falklands the Conservatives returned to the top of the opinion polls by a wide margin and went on to win the following year’s general election by a landslide.[116] Subsequently, Defence Secretary Nott’s proposed cuts to the Royal Navy were abandoned.

The islanders subsequently had full British citizenship restored in 1983, their lifestyle improved by investments Britain made after the war and by the liberalisation of economic measures that had been stalled through fear of angering Argentina. In 1985, a new constitution was enacted promoting self-government, which has continued to devolve power to the islanders.

In Argentina, the Falklands War meant that a possible war with Chile was avoided. Further, Argentina returned to a democratic government in the 1983 general election, the first free general election since 1973. It also had a major social impact, destroying the military’s image as the “moral reserve of the nation” that they had maintained through most of the 20th century.

Various figures have been produced for the number of veterans who have committed suicide since the war. Some studies have estimated that 264 British veterans and 350–500 Argentine veterans have committed suicide since 1982.[117][118][119] However, a detailed study[120] of 21,432 British veterans of the war commissioned by the UK Ministry of Defence found that only 95 had died from “intentional self-harm and events of undetermined intent (suicides and open verdict deaths)”, a ratio no higher than that of the general population.[121]

Military analysis

Militarily, the Falklands conflict remains the largest air-naval combat operation between modern forces since the end of the Second World War. As such, it has been the subject of intense study by military analysts and historians. The most significant “lessons learned” include: the vulnerability of surface ships to anti-ship missiles and submarines, the challenges of co-ordinating logistical support for a long-distance projection of power, and reconfirmation of the role of tactical air power, including the use of helicopters.

In 1986, the BBC broadcast the Horizon programme, In the Wake of HMS Sheffield, which discussed lessons learned from the conflict—and measures since taken to implement them, such as stealth ships and close-in weapon systems.

Memorials

The Monumento a los Caídos en Malvinas (“Monument for the Fallen in the Falklands”) in Plaza San Martín, Buenos Aires; a member of the historic Patricios regiment stands guard.[nb 8]

In addition to memorials on the islands, there is a memorial in the crypt of St Paul’s Cathedral, London to the British war dead.[122] In Argentina, there is a memorial at Plaza San Martín in Buenos Aires,[123] another one in Rosario, and a third one in Ushuaia.

During the war, British dead were put into plastic body bags and buried in mass graves. After the war, the bodies were recovered; 14 were reburied at Blue Beach Military Cemetery and 64 were returned to Britain.

Many of the Argentine dead are buried in the Argentine Military Cemetery west of the Darwin Settlement. The government of Argentina declined an offer by Britain to have the bodies repatriated to the mainland.[124]

Minefields

Although some minefields have been cleared, a substantial number of them still exist in the islands, such as this one at Port William on East Falkland.

As of 2011, there were 113 uncleared minefields on the Falkland Islands and unexploded ordnance (UXOs) covering an area of 13 km2 (5.0 sq mi). Of this area, 5.5 km2 (2.1 sq mi) on the Murrell Peninsula were classified as being “suspected minefields” – the area had been heavily pastured for the previous 25 years without incident. It was estimated that these minefields had 20,000 anti-personnel mines and 5,000 anti-tank mines. No human casualties from mines or UXO have been reported in the Falkland Islands since 1984, and no civilian mine casualties have ever occurred on the islands. The UK reported six military personnel were injured in 1982 and a further two injured in 1983. Most military accidents took place while clearing the minefields in the immediate aftermath of the 1982 conflict or in the process of trying to establish the extent of the minefield perimeters, particularly where no detailed records existed.

On 9 May 2008, the Falkland Islands Government asserted that the minefields, which represent 0.1% of the available farmland on the islands “present no long term social or economic difficulties for the Falklands,” and that the impact of clearing the mines would cause more problems than containing them. However, the British Government, in accordance with its commitments under the Mine Ban Treaty has a commitment to clear the mines by the end of 2019. [125][126] In May 2012, it was announced that 3.7 km2 (1.4 sq mi) of Stanley Common (which lies between the Stanley – Mount Pleasant road and the shoreline) was made safe and had been opened to the public, opening up a 3-kilometre (1.9 mi) stretch of coastline and a further two kilometres of shoreline along Mullet’s Creek.[127]

Press and publicity

Argentina

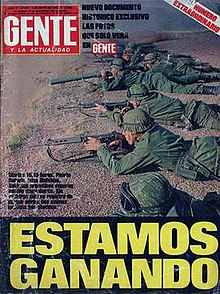

Selected war correspondents were regularly flown to Port Stanley in military aircraft to report on the war. Back in Buenos Aires, newspapers and magazines faithfully reported on “the heroic actions of the largely conscript army and its successes”.[17]

Officers from the intelligence services were attached to the newspapers and ‘leaked’ information confirming the official communiqués from the government. The glossy magazines Gente and Siete Días swelled to 60 pages with colour photographs of British warships in flames – many of them faked – and bogus eyewitness reports of the Argentine commandos’ guerrilla war on South Georgia (6 May) and an already dead Pucará pilot’s attack on HMS Hermes[17] (Lt. Daniel Antonio Jukic had been killed at Goose Green during a British air strike on 1 May). Most of the faked photos actually came from the tabloid press. One of the best remembered headlines was “Estamos ganando” (“We’re winning”) from the magazine Gente, that would later use variations of it.[128]

The Argentine troops on the Falkland Islands could read Gaceta Argentina—a newspaper intended to boost morale among the servicemen. Some of its untruths could easily be unveiled by the soldiers who recovered corpses.[129]

The Malvinas course united the Argentines in a patriotic atmosphere that protected the junta from critics, and even opponents of the military government supported Galtieri; Ernesto Sabato said: “Don’t be mistaken, Europe; it is not a dictatorship who is fighting for the Malvinas, it is the whole Nation. Opponents of the military dictatorship, like me, are fighting to extirpate the last trace of colonialism.”[130] The Madres de Plaza de Mayo were even exposed to death threats from ordinary people.[17]

HMS Invincible was repeatedly sunk in the Argentine press,[131] and on 30 April 1982 the Argentine magazine Tal Cual showed Prime Minister Thatcher with an eyepatch and the text: Pirate, witch and assassin. Guilty![132] Three British reporters sent to Argentina to cover the war from the Argentine perspective were jailed until the end of the war.[133]

United Kingdom

Seventeen newspaper reporters, two photographers, two radio reporters and three television reporters with five technicians sailed with the Task Force to the war. The Newspaper Publishers’ Association selected them from among 160 applicants, excluding foreign media. The hasty selection resulted in the inclusion of two journalists among the war reporters who were interested only in Queen Elizabeth II’s son Prince Andrew, who was serving in the conflict.[134] The Prince flew a helicopter on multiple missions, including anti-surface warfare, Exocet missile decoy and casualty evacuation.

Merchant vessels had the civilian Inmarsat uplink, which enabled written telex and voice report transmissions via satellite. SS Canberra had a facsimile machine that was used to upload 202 pictures from the South Atlantic over the course of the war. The Royal Navy leased bandwidth on the US Defense Satellite Communications System for worldwide communications. Television demands a thousand times the data rate of telephone, but the Ministry of Defence was unsuccessful in convincing the US to allocate more bandwidth.[135]

TV producers suspected that the enquiry was half-hearted; since the Vietnam War television pictures of casualties and traumatised soldiers were recognised as having negative propaganda value. However, the technology only allowed uploading a single frame per 20 minutes – and only if the military satellites were allocated 100% to television transmissions. Videotapes were shipped to Ascension Island, where a broadband satellite uplink was available, resulting in TV coverage being delayed by three weeks.[135]

The press was very dependent on the Royal Navy, and was censored on site. Many reporters in the UK knew more about the war than those with the Task Force.[135]

The Royal Navy expected Fleet Street to conduct a Second World War-style positive news campaign[136] but the majority of the British media, especially the BBC, reported the war in a neutral fashion.[137] These reporters referred to “the British troops” and “the Argentinian troops” instead of “our lads” and the “Argies”.[138] The two main tabloid papers presented opposing viewpoints: The Daily Mirror was decidedly anti-war, whilst The Sun became well known for headlines such as “Stick It Up Your Junta!,” which, along with the reporting in other tabloids,[139] led to accusations of xenophobia[131] [139][140] and jingoism.[131] [140][141][142] The Sun was condemned for its “Gotcha” headline following the sinking of the ARA General Belgrano.[143][144][145]

Cultural impact

There were wide-ranging influences on popular culture in both the UK and Argentina, from the immediate postwar period to the present. The then elderly Argentinian writer Jorge Luis Borges described the war as “a fight between two bald men over a comb”.[146] The words yomp and Exocet entered the British vernacular as a result of the war. The Falklands War also provided material for theatre, film and TV drama and influenced the output of musicians. In Argentina, the military government banned the broadcasting of music in the English language, giving way to the rise of local rock musicians.[147]

WikiMiniAtlas

WikiMiniAtlas