Remembrance Day Poppy

——————————————————————————

In Flanders Fields

——————————————————————————

Wear it with PRIDE

—————————————————————————————–

John McCrae’s War – In Flanders Fields – Documentary

—————————————————————————————–

John McCrae

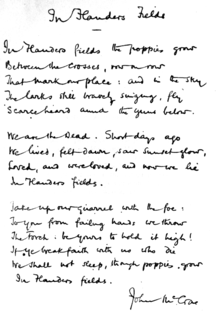

“In Flanders Fields” is a war poem in the form of a rondeau, written during the First World War by Canadian physician Major John McCrae. He was inspired to write it on May 3, 1915, after presiding over the funeral of friend and fellow soldier Alexis Helmer, who died in the Second Battle of Ypres.

According to legend, fellow soldiers retrieved the poem after McCrae, initially dissatisfied with his work, discarded it. “In Flanders Fields” was first published on December 8 of that year in the London-based magazine Punch.

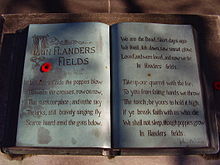

Inscription of the complete poem in a bronze “book” at the John McCrae memorial at his birthplace in Guelph, Ontario, Canada.

It is one of the most popular and most quoted poems from the war. As a result of its immediate popularity, parts of the poem were used in propaganda efforts and appeals to recruit soldiers and raise money selling war bonds. Its references to the red poppies that grew over the graves of fallen soldiers resulted in the remembrance poppy becoming one of the world’s most recognized memorial symbols for soldiers who have died in conflict. The poem and poppy are prominent Remembrance Day symbols throughout the Commonwealth of Nations, particularly in Canada, where “In Flanders Fields” is one of the nation’s best-known literary works. The poem also has wide exposure in the United States, where it is associated with Memorial Day.

Backgound

John McCrae was a poet and physician from Guelph, Ontario. He developed an interest in poetry at a young age and wrote throughout his life. His earliest works were published in the mid-1890s in Canadian magazines and newspapers. McCrae’s poetry often focused on death and the peace that followed.

At the age of 41, McCrae enrolled with the Canadian Expeditionary Force following the outbreak of the First World War. He had the option of joining the medical corps because of his training and age, but he volunteered instead to join a fighting unit as a gunner and medical officer.

It was his second tour of duty in the Canadian military. He had previously fought with a volunteer force in the Second Boer War. He considered himself a soldier first; his father was a military leader in Guelph and McCrae grew up believing in the duty of fighting for his country and empire.

McCrae fought in the second battle of Ypres in the Flanders region of Belgium where the German army launched one of the first chemical attacks in the history of war. They attacked the Canadian position with chlorine gas on April 22, 1915, but were unable to break through the Canadian line, which held for over two weeks. In a letter written to his mother, McCrae described the battle as a “nightmare”:

“For seventeen days and seventeen nights none of us have had our clothes off, nor our boots even, except occasionally. In all that time while I was awake, gunfire and rifle fire never ceased for sixty seconds…. And behind it all was the constant background of the sights of the dead, the wounded, the maimed, and a terrible anxiety lest the line should give way.”

Alexis Helmer, a close friend, was killed during the battle on May 2. McCrae performed the burial service himself, at which time he noted how poppies quickly grew around the graves of those who died at Ypres. The next day, he composed the poem while sitting in the back of an ambulance at an Advanced Dressing Station outside Ypres.

This location is today known as the John McCrae Memorial Site.

The first chapter of In Flanders Fields and Other Poems, a 1919 collection of McCrae’s works, gives the text of the poem as follows:

In Flanders fields the poppies blow

Between the crosses, row on row,

That mark our place; and in the sky

The larks, still bravely singing, fly

Scarce heard amid the guns below.

We are the Dead. Short days ago

We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow,

Loved and were loved, and now we lie

In Flanders fields.

Take up our quarrel with the foe:

To you from failing hands we throw

The torch; be yours to hold it high.

If ye break faith with us who die

We shall not sleep, though poppies grow

In Flanders fields.

As with his earlier poems, “In Flanders Fields” continues McCrae’s preoccupation with death and how it stands as the transition between the struggle of life and the peace that follows. It is written from the point of view of the dead. It speaks of their sacrifice and serves as their command to the living to press on.

As with many of the most popular works of the First World War, it was written early in the conflict, before the romanticism of war turned to bitterness and disillusion for soldiers and civilians alike.

Publication

Cyril Allinson was a sergeant major in McCrae’s unit. While delivering the brigade’s mail, he watched McCrae as he worked on the poem, noting that McCrae’s eyes periodically returned to Helmer’s grave as he wrote. When handed the notepad, Allinson read the poem and was so moved he immediately committed it to memory.

He described it as being “almost an exact description of the scene in front of us both”.

According to legend, McCrae was not satisfied with his work. It is said he crumpled the paper and threw it away. It was retrieved by a fellow member of his unit, either Edward Morrison or J. M. Elder, or Allinson himself. McCrae was convinced to submit the poem for publication.

Another story of the poem’s origin claimed that Helmer’s funeral was actually held on the morning of May 2, after which McCrae wrote the poem in 20 minutes. A third claim, by Morrison, was that McCrae worked on the poem as time allowed between arrivals of wounded soldiers in need of medical attention.

Regardless of its true origin, McCrae worked on the poem for months before considering it ready for publication. He submitted it to The Spectator in London, but it was rejected. It was then sent to Punch, where it was published on December 8, 1915. It was published anonymously, but Punch attributed the poem to McCrae in its year-end index.

The word that ends the first line of the poem has been disputed. According to Allinson, the poem began with “In Flanders Fields the poppies grow” when first written.

However, since McCrae ended the second-to-last line with “grow”, Punch received permission to change the wording of the opening line to end with “blow”. McCrae himself used either word when making handwritten copies for friends and family.

Questions over how the first line should end have endured since publication. Most recently, the Royal Canadian Mint was inundated with queries and complaints from those who believed the first line should end with “grow” when a design for the ten-dollar bill was released in 2001 that featured the first stanza of “In Flanders Fields”, ending the first line with “blow”.

In song

It was set to music by Frank E. Tours. The score was published in New York and Chicago by M. Witmark & Sons in 1918.

Popularity

According to historian Paul Fussell, “In Flanders Fields” was the most popular poem of its era. McCrae received numerous letters and telegrams praising his work when he was revealed as the author.

The poem was republished throughout the world, rapidly becoming synonymous with the sacrifice of the soldiers who died in the First World War. It was translated into numerous languages, so many that McCrae himself quipped that:

“it needs only Chinese now, surely”.

Its appeal was nearly universal. Soldiers took encouragement from it as a statement of their duty to those who died while people on the home front viewed it as defining the cause for which their brothers and sons were fighting.

It was often used for propaganda, particularly in Canada by the Unionist Party during the 1917 federal election amidst the Conscription Crisis. French Canadians in Quebec were strongly opposed to the possibility of conscription, but English Canadians voted overwhelmingly to support Prime Minister Robert Borden and the Unionist government. “In Flanders Fields” was said to have done more to “make this Dominion persevere in the duty of fighting for the world’s ultimate peace than all the political speeches of the recent campaign”.

McCrae, a staunch supporter of the empire and the war effort, was pleased with the effect his poem had on the election. He stated in a letter: “I hope I stabbed a [French] Canadian with my vote.”

The poem was a popular motivational tool in Great Britain, where it was used to encourage soldiers fighting against Germany, and in the United States where it was reprinted across the country. It was one of the most quoted works during the war, used in many places as part of campaigns to sell war bonds, during recruiting efforts and to criticize pacifists and those who sought to profit from the war.

American composer Charles Ives used “In Flanders Fields” as the basis for a song of the same name that premiered in 1917. Fussell criticized the poem in his work The Great War and Modern Memory (1975).He noted the distinction between the pastoral tone of the first nine lines and the “recruiting-poster rhetoric” of the third stanza. Describing it as “vicious” and “stupid”, Fussell called the final lines a “propaganda argument against a negotiated peace”.

Legacy

McCrae was moved to the medical corps and stationed in Boulogne, France, in June 1915 where he was promoted to Lieutenant-Colonel, and placed in charge of medicine at the Number 3 Canadian General Hospital. He was promoted to the acting rank of Colonel on January 13, 1918, and named Consulting Physician to the British Armies in France. The years of war had worn McCrae down, however. He contracted pneumonia that same day, and later came down with cerebral meningitis.

On January 28, 1918, he died at the military hospital in Wimereux and was buried there with full military honours.

A book of his works, featuring “In Flanders Fields” was published the following year.

“In Flanders Fields” has attained iconic status in Canada, where it is a staple of Remembrance Day ceremonies and may be the most well known literary piece among English Canadians.

It has an official French adaptation, entitled “Au champ d’honneur“, written by Jean Pariseau and used by the Canadian government in French and bilingual ceremonies.

In addition to its appearance on the ten-dollar bill, the Royal Canadian Mint has released poppy-themed quarters on several occasions. A version minted in 2004 featured a red poppy in the centre and is considered the first multi-coloured circulation coin in the world.Among its uses in popular culture, the line “to you from failing hands we throw the torch, be yours to hold it high” has served as a motto for the Montreal Canadiens hockey club since 1940.

McCrae’s birthplace in Guelph, Ontario has been converted into a museum dedicated to his life and the war. In Belgium, the In Flanders Fields Museum in Ypres, named after the poem and devoted to the First World War, is situated in one of Flanders’ largest tourist areas.

Despite its enduring fame, “In Flanders Fields” is often ignored by academics teaching and discussing Canadian literature. The poem is sometimes viewed as an anachronism; It spoke of glory and honour in a war that has since become synonymous with the futility of trench warfare and the wholesale slaughter produced by 20th century weaponry.

Nancy Holmes, professor at the University of British Columbia, speculated that its patriotic nature and usage as a tool for propaganda may have led literary critics to view it as a national symbol or anthem rather than a poem.

Remembrance poppies

Poppy wreaths at the Menin Gate in Ypres, Belgium

The red poppies that McCrae referred to had been associated with war since the Napoleonic Wars when a writer of that time first noted how the poppies grew over the graves of soldiers. The damage done to the landscape in Flanders during the battle greatly increased the lime content in the surface soil, leaving the poppy as one of the few plants able to grow in the region.

Inspired by “In Flanders Fields”, American professor Moina Michael resolved at the war’s conclusion in 1918 to wear a red poppy year-round to honour the soldiers who had died in the war. She also wrote a poem in response called “We Shall Keep the Faith“.

She distributed silk poppies to her peers and campaigned to have them adopted as an official symbol of remembrance by the American Legion. Madame E. Guérin attended the 1920 convention where the Legion supported Michael’s proposal and was herself inspired to sell poppies in her native France to raise money for the war’s orphans.

In 1921, Guérin sent poppy sellers to London ahead of Armistice Day, attracting the attention of Field Marshal Douglas Haig. A co-founder of The Royal British Legion, Haig supported and encouraged the sale. The practice quickly spread throughout the British Empire. The wearing of poppies in the days leading up to Remembrance Day remains popular in many areas of the Commonwealth of Nations, particularly Great Britain, Canada, and South Africa, and in the days leading up to ANZAC Day in Australia and New Zealand.

———————————

The Remembrance Poppy

———————————

The remembrance poppy (a Papaver rhoeas) has been used since 1921 to commemorate soldiers who have died in war. Inspired by the World War I poem “In Flanders Fields“, and promoted by Moina Michael, they were first adopted by the American Legion to commemorate American soldiers killed in that war (1914–1918). They were then adopted by military veterans‘ groups in parts of the former British Empire: the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia and New Zealand.

Today, they are most common in the UK and Canada, and are used to commemorate their servicemen and women killed in all conflicts since 1914. There, small artificial poppies are often worn on clothing for a few weeks prior to Remembrance Day/Armistice Day (11 November).

Poppy wreaths are also often laid at war memorials.

The remembrance poppy is especially prominent in the UK. In the weeks leading up to Remembrance Sunday, they are distributed by The Royal British Legion in return for donations to their “Poppy Appeal”, which supports all current and former British military personnel. During this time, it is an unwritten rule that all public figures and people appearing on television must wear them; some have berated this as “poppy fascism” and argued that the Appeal is being used to glorify current wars.

It is especially controversial in Northern Ireland; most Irish nationalists and Irish Catholics refuse to wear one, mainly due to actions of the British Army during the Troubles, while Ulster Protestants and Unionists usually wear them.

Origins

The use of the poppy was inspired by the World War I poem “In Flanders Fields“. Its opening lines refer to the many poppies that were the first flowers to grow in the churned-up earth of soldiers’ graves in Flanders, a region of Europe that overlies a part of Belgium.

The poem was written by Canadian physician and Lieutenant Colonel John McCrae on 3 May 1915 after witnessing the death of his friend, a fellow soldier, the day before. The poem was first published on 8 December 1915 in the London-based magazine Punch.

In 1918, Moina Michael, who had taken leave from her professorship at the University of Georgia to be a volunteer worker for the American YWCA, was inspired by the poem and published a poem of her own called “We Shall Keep the Faith“.

In tribute to McCrae’s poem, she vowed to always wear a red rememberance poppy as a symbol of remembrance for those who fought and helped in the war. At a November 1918 YWCA Overseas War Secretaries’ conference, she appeared with a silk poppy pinned to her coat and distributed 25 more to those attending. She then campaigned to have the poppy adopted as a national symbol of remembrance.

At a conference in 1920, the National American Legion adopted it as their official symbol of remembrance. At this conference, French-woman Anna E. Guérin was inspired to introduce the artificial poppies commonly used today. In 1921 she sent her poppy sellers to London, where they were adopted by Field Marshal Douglas Haig, a founder of the Royal British Legion. It was also adopted by veterans’ groups in Canada, Australia and New Zealand.

Usage

Canada

In Canada, the poppy is the official symbol of remembrance worn during the two weeks before 11 November, having been adopted in 1921. The Royal Canadian Legion, which has trademarked the image, suggests that poppies be worn on the left lapel, or as near the heart as possible.

Until 1996, poppies were made by disabled veterans in Canada, but they have since been made by a private contractor. The Canadian poppies consist of two pieces of moulded plastic covered with flocking with a pin to fasten them to clothing. At first the poppies were made with a black centre. From 1980 to 2002, the centres were changed to green. Current designs are black only; this change caused confusion and controversy to those unfamiliar with the original design.

In 2007, sticker versions of the poppy were made for children, the elderly, and healthcare and food industry workers. Canada also issues a cast metal “Canada Remembers” pin featuring a gold maple leaf and two poppies, one representing the fallen and the other representing those who remained on the home front.

Following the installation of the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier at the National War Memorial in Ottawa in 2000, where the national Remembrance service is held, a new tradition formed spontaneously as attendees laid their poppies on the tomb at the end of the service. This tradition, while not part of the official program, has become widely practised elsewhere in the country, with others leaving cut flowers, photographs, or letters to the deceased.

The poppy is also worn on Memorial Day, celebrated on July 1 each year in Newfoundland and Labrador.

United Kingdom

A poppy on a bus in Southampton, England (November 2008)

In the United Kingdom, remembrance poppies are sold by The Royal British Legion (RBL). This is a charity providing financial, social, political and emotional support to those who have served or who are currently serving in the British Armed Forces, and their dependants. They are sold on the streets by volunteers in the weeks before Remembrance Day. Other products bearing the Poppy, the Trademark of The Royal British Legion are sold throughout the year as part of the ongoing fundraising.

The RBL state,

“The red poppy is our registered mark and its only lawful use is to raise funds for the Poppy Appeal”;

its yearly fundraising drive in the weeks before Remembrance Day. The RBL says these poppies are:

“worn to commemorate the sacrifices of our Armed Forces and to show support to those still serving today”.

In England, Wales, and Northern Ireland, the poppies have two red paper petals, a green paper leaf and are mounted on a green plastic stem. In Scotland, the poppies are curled and have four petals with no leaf. The yearly selling of poppies is a major source of income for the RBL in the UK. The poppy has no fixed price; it is sold for a donation or the price may be suggested by the seller. The black plastic center of the poppy was marked “Haig Fund” until 1994 but is now marked “Poppy Appeal”.

A team of about 50 people—most of them disabled former British military personnel—work all year round to make millions of poppies at the Poppy Factory in Richmond. Scottish poppies are made in the Lady Haig Poppy Factory in Edinburgh.

In the early years after World War I, poppies were worn only on Remembrance Day itself. However, today the RBL’s “Poppy Appeal” has a higher profile than any other charity appeal in the UK. The poppies are widespread from late October until mid-November every year and are worn by the general public, politicians, the Royal Family and others in public life. It has also become common to see poppies on cars, lorries and public transport such as aeroplanes, buses, and trams. Many magazines and newspapers also show a poppy on their cover page, and some social network users add poppies to their avatars.

In 2011, a Second World War plane dropped 6,000 poppies over the town of Yeovil in Somerset.

Some have criticised the level of compulsion associated with the custom, something Channel 4 newsreader Jon Snow has called “poppy fascism”. Columnist Dan O’Neill wrote that “presenters and politicians seem to compete in a race to be first – poppies start sprouting in mid-October while the absence of a poppy is interpreted as absence of concern for the war dead, almost as an unpatriotic act of treachery”.

Likewise, Jonathan Bartley of the religious think-tank Ekklesia said “public figures in Britain are urged, indeed in many cases, required, to wear … the red poppy, almost as an article of faith. There is a political correctness about the red poppy”.

Journalist Robert Fisk complained that the poppy has become a seasonal “fashion accessory” and that people were “ostentatiously wearing a poppy for social or work-related reasons, to look patriotic when it suited them”. Kleshna, one of two businesses with an exclusive tie-in with the RBL, sells expensive crystal-clad poppy jewellery that has been worn by celebrities. In 1997 and again in 2000 the Royal British Legion registered the Poppy under Intellectual Property Rights (1997 Case EU000557058) and Trade Mark (2000 Trade Mark 2239583).

Northern Ireland

The Royal British Legion also holds a yearly poppy appeal in Northern Ireland and in 2009 raised more than £1 million. However, the wearing of poppies in Northern Ireland is controversial. It is seen by many as a political symbol and a symbol of Britishness, representing support for the British Army.

The poppy has long been the preserve of the unionist/loyalist community. Loyalist paramilitaries (such as the UVF and UDA) have also used poppies to commemorate their own members who were killed in The Troubles.

Most Irish nationalists/republicans, and members of the Irish Catholic community, choose not to wear poppies; they regard the Poppy Appeal as supporting soldiers who killed Irish civilians (for example on Bloody Sunday) and who colluded with illegal loyalist paramilitaries (for example the Glenanne gang) during The Troubles.

In 2008, the director of Relatives for Justice condemned the wearing of poppies by police officers in Irish nationalist areas, calling it “repugnant and offensive to the vast majority of people within our community, given the role of the British Army“.

In 2009, Sinn Féin‘s Glenn Campbell berated the policy that all BBC TV presenters must wear poppies in the run-up to Remembrance Day and urged the BBC to drop the policy, as it is a publicly funded body. In the Irish Independent, it was claimed that “substantial amounts” of money raised from selling poppies are used “to build monuments to insane or inane generals or build old boys’ clubs for the war elite”.

However, on Remembrance Day 2010 the SDLP’s Margaret Ritchie was the first leader of a nationalist party to wear one.

Republic of Ireland

During World War I, all of Ireland was part of the UK and about 200,000 Irishmen fought in the British Army (see Ireland and World War I). Although the British Army is banned from actively recruiting in the Republic of Ireland, some of its citizens still enlist.

The RBL thus has a branch in the Republic and holds a yearly Poppy Appeal there.

Each July, the Republic has its own National Day of Commemoration for all Irish people who died in war. However, the wearing of poppies is much less common than in the UK and they are not part of the main commemorations. This is partly due to the British Army’s role in fighting against Irish independence, its activities during the War of Independence (for example the Burning of Cork) and the British Army’s role in Northern Ireland during the Troubles. Nevertheless, the RBL holds its own wreath-laying ceremony at St Patrick’s Cathedral, Dublin, which the President of Ireland has attended.

United States

In the United States, the Veterans of Foreign Wars conducted the first nationwide distribution of remembrance poppies before Memorial Day in 1922. Today, the American Legion Auxiliary distributes crepe-paper poppies in exchange for donations around Memorial Day and Veterans Day.

Elsewhere

In Hong Kong—which was formerly part of the British Empire—the poppy is worn by some participants on Remembrance Sunday each year. It is not generally worn by the public, although The Royal British Legion’s Hong Kong and China Branch sells poppies to the public in a few places on the Hong Kong Island only.

Never Again symbol from Ukraine

During Victory Day 2014—which marks Nazi Germany’s surrender to the Soviet Union—some Ukrainians wore remembrance poppies instead of the usual Ribbon of Saint George, as the ribbon had become associated with pro-Russian separatists. A poppy logo was designed by Sergiy Mishakin, containing the text: “1939-1945 Never Again”.

From 2015 also official symbol of Remembrance and Reconciliation (May 8) and Victory Day over Nazism in World War II (May 9) days.

In Pakistan, in Northern Punjab and a few parts of the North-West Frontier (now Khyber Pakhtunkhwa), a private ceremony is celebrated each 11 November where red poppies are worn, by direct descendants of World War 1 veterans from the old British Indian Army belonging to these parts; these people belong to the ‘Great War Company’, a non-governmental, non-profit organisation.

In Albania, government representatives including Prime-Minister Edi Rama, Speaker of the House Ilir Meta, and Minister of Defense Mimi Kodheli, wore the Remembrance Poppy during the commemoration ceremonies for the 70th Anniversary of the Liberation of Albania, in November 2014.

Other designs and purposes

White poppies

A white poppy left on Anzac Day in New Zealand, 2009

Some people choose to wear white poppies as a pacifist alternative to the red poppy. The white poppy and white poppy wreaths were introduced by Britain’s Co-operative Women’s Guild in 1933.

Today, white poppies are sold by Peace Pledge Union or may be home-made.

Purple poppies

To commemorate animal victims of war, Animal Aid in Britain has issued a purple poppy, which can be worn alongside the traditional red one, as a reminder that both humans and animals have been – and continue to be – victims of war.

Protests and controversy

Football clubs commonly wear jerseys with a poppy emblazoned on, as Celtic controversially did in 2010.

In 1993, The Royal British Legion complained about the logo of the game Cannon Fodder, because its use of iconography closely resembling of remembrance poppy. The Royal British pronunciated about, saying that was ‘sick and degenerate’ before its release trying to ban the game. A newspaper quoted the British Legion, Liberal Democrat MP Menzies Campbell and Viscount Montgomery of Alamein, calling the game offensive to “millions”, “monstrous” and “very unfortunate” respectively.

In the run-up to Remembrance Day, it has become common for UK football teams to play with artificial poppies sewn to their shirts, at the request of the Royal British Legion. This has caused some controversy. At a Celtic v Aberdeen match in November 2010, a group of Celtic supporters, called the Green Brigade, unfurled a large banner in protest at the team wearing poppies.

In a statement, it said:

“Our group and many within the Celtic support do not recognise the British Armed Forces as heroes, nor their role in many conflicts as one worthy of our remembrance”.

It gave Operation Banner (Northern Ireland), the Afghanistan War and the Iraq War as examples. In November 2011, it was proposed that the England football team should wear poppies on their shirts in a match against Spain. However, FIFA turned down the proposal, saying it would “open the door to similar initiatives” across the world, “jeopardising the neutrality of football”.

FIFA’s decision was attacked by Prince William and Prime Minister David Cameron, who said he would back any player who ignored the ban.

Members of the English Defence League (EDL) held a protest on the roof of FIFA’s headquarters in Zurich. Instead, the English Football Association came up with other ways to mark Remembrance Day; for example, the England players would wear poppies before kickoff and black armbands during the match, there would be a minute’s silence, a poppy wreath would be set on the pitch during the national anthems, poppies would be sold in the stadium and would be shown on the scoreboards and advertising boards.

FIFA subsequently allowed the English, Scottish and Welsh teams to wear poppies on black armbands. Irish footballer James McClean, who has played for a number of English teams, has received death threats and abuse since 2012 for refusing to wear a poppy on his shirt during matches. McClean is from Derry, where British soldiers shot dead 14 unarmed civilians on Bloody Sunday.

Other public figures have also been attacked for not wearing poppies. British journalist and newsreader Charlene White has faced racist and sexist abuse for not wearing a poppy on-screen. She explained “I prefer to be neutral and impartial on screen so that one of those charities doesn’t feel less favoured than another”.

Newsreader Jon Snow does not wear a poppy on-screen for similar reasons. He too was criticized and he condemned what he saw as “poppy fascism”. Well-known war-time journalist Robert Fisk published in November 2011 a personal account about the shifting nature of wearing a poppy, titled

“Do those who flaunt the poppy on their lapels know that they mock the war dead?”.

British Prime Minister David Cameron rejected a request from Chinese officials to remove his poppy during his visit to Beijing on Remembrance Day 2010. The poppy was deemed offensive because of its association with the Anglo-Chinese Opium Wars in the 19th century, after which the Qing Dynasty was forced to tolerate the British opium trade in China and to cede Hong Kong to the UK.

However, Cameron wore a poppy in October 2015 when he met Chinese President Xi Jinping in London.

A 2010 Remembrance Day ceremony in London was disrupted by members of Muslims Against Crusades, who were protesting against British Army actions in Afghanistan and Iraq. They burnt large poppies and chanted “British soldiers burn in hell” during the two-minute silence. Two of the men were arrested and charged for threatening behaviour. One was convicted and fined £50.

The same group planned to hold another protest in 2011, but was banned by the Home Secretary the day before the planned protest.

In recent years, people have been arrested in the UK for burning remembrance poppies. In November 2011 a number of people were arrested in Northern Ireland after a picture of two youths burning a poppy was posted on Facebook. The picture was reported to police by a member of the RBL.

The following year, a young Canterbury man was arrested for allegedly posting a picture of a burning poppy on Facebook, on suspicion of an offence under the Malicious Communications Act.

In 2011 it was revealed that Kleshna, one of two businesses selling its own poppies on the RBL website, gives only 10% of its sales to charity. Kleshna sells crystal-clad poppy jewellery which has been worn by celebrities on television

—————————————-

Visit the website or make a donation:

Reblogged this on Belfast Child.

LikeLike