Northern Ireland 1969

Timeline & Deaths 1969

1960–1969

Main Events

Since 1964, civil rights activists had been protesting against the discrimination against Catholics and Irish nationalists by the Ulster Protestant and unionist government of Northern Ireland. The civil rights movement called for: ‘one man, one vote‘; the end to gerrymandered electoral boundaries; the end to discrimination in employment and in the allocation of public housing; repeal of the Special Powers Act (which was used to intern both constitutional nationalist and republican activists); and the disbanding of the Ulster Special Constabulary (more commonly known as the B-Specials, an overwhelmingly Protestant reserve police force which was known for police brutality toward Catholics).[6]

1966

| April |

Loyalists led by Ian Paisley, a Protestant fundamentalist preacher, founded the Ulster Constitution Defence Committee (UCDC) to oppose the civil rights movement. It set up a paramilitary-style wing called the Ulster Protestant Volunteers (UPV).[6] |

| 21 May |

A loyalist group calling itself the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) issued a statement declaring war on the Irish Republican Army (IRA). The group claimed to be composed of “heavily armed Protestants dedicated to this cause”.[7] At the time, the IRA was not engaged in armed action, but Irish nationalists/republicans were marking the 50th anniversary of the Easter Rising. Some unionists and loyalists warned “that a revival of the IRA was imminent”.[6] |

| May–June |

The UVF carried out three attacks on Irish Catholics in Belfast. In the first, a Protestant civilian died when UVF members firebombed the Catholic-owned pub beside her house. In the second, a Catholic civilian was shot dead as he walked home. In the third, the UVF opened-fire on three Catholic civilians as they left a pub, killing one and wounding the others.[6] |

1968

| 20 June |

Civil rights activists (including Stormont MP Austin Currie) protested against discrimination in the allocation of housing by illegally occupying a house in Caledon, County Tyrone. An unmarried Protestant woman (the secretary of a local Unionist politician) had been given the house ahead of Catholic families with children. The protesters were forcibly removed by the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC).[8] |

| 24 August |

Northern Ireland’s first civil rights march was held. Many more marches would be held over the following year. Loyalists attacked some of the marches and organized counter-demonstrations to get the marches banned.[8] |

| 5 October |

A civil rights march was to take place in Derry. When the loyalist Apprentice Boys announced its intention to hold a march at the same place and time, the Government banned the civil rights march. When civil rights activists defied the ban, RUC officers surrounded the marchers and beat them indiscriminately and without provocation.[9] Over 100 people were injured, including a number of MPs.[9] This sparked two days of serious rioting in Derry between Catholics and the RUC. Some consider this to be the beginning of the Troubles.[8] |

| 9 October |

About 2,000 students from Queen’s University Belfast tried to march to Belfast City Hall in protest against ‘police brutality’ on 5 October in Derry. The march was blocked by loyalists led by Ian Paisley. After the demonstration, a student civil rights group—People’s Democracy—was formed.[8] |

1969

| 4 January |

A People’s Democracy march between Belfast and Derry was repeatedly attacked by loyalists. At Burntollet it was ambushed by 200 loyalists and off-duty police (RUC) officers armed with iron bars, bricks and bottles. The marchers claimed that police did little to protect them. When the march arrived in Derry it was broken up by the RUC, which sparked serious rioting between Irish nationalists and the RUC.[10] That night, RUC officers went on a rampage in the Bogside area of Derry; attacking Catholic homes, attacking and threatening residents, and hurling sectarian abuse.[11] Residents then sealed off the Bogside with barricades to keep the police out, creating “Free Derry“. |

| March–April |

Loyalists—members of the UVF and UPV—bombed water and electricity installations in Northern Ireland, blaming them on the dormant IRA and on elements of the civil rights movement. The loyalists intended to bring down the Unionist Prime Minister of Northern Ireland, Terence O’Neill, who had promised some concessions to the civil rights movement. There were six bombings and all were widely blamed on the IRA. As a response, British soldiers were sent to guard installations. Unionist support for O’Neill waned, and on 28 April he resigned as Prime Minister.[12] |

| 17 April |

People’s Democracy activist Bernadette Devlin became the youngest woman ever elected to Westminster. |

| 19 April |

During clashes with civil rights marchers in Derry, RUC officers entered the house of uninvolved Catholic civilian Samuel Devenny, and beat him along with two of his teenage daughters.[13] One of the daughters was beaten unconscious as she lay recovering from surgery.[14] Devenny suffered a heart attack and died on 17 July from his injuries. |

| 13 July |

During clashes with nationalists in Dungiven, RUC officers beat an uninvolved Catholic bystander; Francis McCloskey (67). He died of his injuries the nex day. Many consider this the first death of the Troubles.[15] |

| 5 August |

The UVF planted their first bomb in the Republic of Ireland, damaging the RTÉ Television Centre in Dublin.[16] |

| 12–14 August |

Battle of the Bogside – during an Apprentice Boys march, serious rioting erupted in Derry between Irish nationalists and the RUC. RUC officers, backed by loyalists, entered the nationalist Bogside in armoured cars and tried to suppress the riot by using CS gas, water cannon and eventually firearms. The almost continuous rioting lasted for two days.[17] |

| 14–17 August |

Northern Ireland riots of August 1969 – in response to events in Derry, Irish nationalists held protests throughout Northern Ireland. Some of these became violent. In Belfast, loyalists responded by attacking nationalist districts. Rioting also erupted in Newry, Armagh, Crossmaglen, Dungannon, Coalisland and Dungiven. Eight people were shot dead and at least 133 were treated for gunshot wounds. Scores of houses and businesses were burnt-out, most of them owned by Catholics. Thousands of families, mostly Catholics, were forced to flee their homes and refugee camps were set up in the Republic.[17]The British Army was deployed on the streets of Northern Ireland, which marked the beginning of Operation Banner. |

| 11 October |

Three people were shot dead during street violence in the loyalist Shankill area of Belfast. Two were Protestant civilians shot by the British Army and one was an RUC officer shot by the UVF. He was the first RUC officer to be killed in the Troubles. The loyalists “had taken to the streets in protest at the Hunt Report, which recommended the disbandment of the B Specials and disarming of the RUC”.[18] |

| October–December |

The UVF detonated bombs in the Republic of Ireland. In Dublin it detonated a car bomb near the Garda central detective bureau.[19] It also bombed a power station at Ballyshannon, a Wolfe Tone memorial in Bodenstown, and the Daniel O’Connell monument in Dublin. |

| December |

A split formed in the Irish Republican Army, creating what was to become the Official IRA (OIRA) and Provisional IRA (PIRA). |

Battle of Bogside August 1969

During 12–17 August 1969, Northern Ireland was rocked by intense political and sectarian rioting. There had been sporadic violence throughout the year arising from the civil rights campaign, which was demanding an end to discrimination against Irish Catholics. Civil rights marches were repeatedly attacked by both Ulster Protestant loyalists and by the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC), a unionist and largely Protestant police force.

The disorder led to the Battle of the Bogside in Derry, a three-day riot in the Bogside district between the RUC and the nationalist/Catholic residents. In support of the Bogsiders, nationalists and Catholics launched protests elsewhere in Northern Ireland. Some of these led to attacks by loyalists working alongside the police. The most bloody rioting was in Belfast, where seven people were killed and hundreds more wounded. Scores of houses, most of them owned by Catholics, as well as businesses and factories were burned-out. In addition, thousands of mostly Catholic families were driven from their homes. In certain areas, the RUC helped the loyalists and failed to protect Catholic areas. Events in Belfast have been viewed by some as a pogrom against the Catholic and nationalist minority.[1][2][3]

The British Army was deployed to restore order and state control and peace lines began to be built to separate the two sides.

The events of August 1969 are widely seen as the beginning of the thirty-year conflict known as the Troubles.

—————————————————————————

1969

The were 16 deaths in 1969 . This would remain the lowest year for deaths until twenty years later in 1999 when there were only 8 deaths . The intervening years saw the slaughter increase substantially and 1972 was by far the worse year for deaths with an incredible 480 murders on the streets of Northern Ireland and mainland Britain.

– 1969 Deaths –

9 Catholic

7 Protestant

Total 16

Annual Killings by Military and Paramilitary Groups 1969

| Year |

Republican

|

Loyalist

|

British

|

Others

|

Total

|

| 1969 |

3

|

3

|

10

|

0

|

16

|

———————————————————————————

Remembering all Innocent victims of the Troubles

“To live in hearts we leave behind is not to die

– Thomas Campbell

To the innocent on the list – Your memory will live forever

– To the Paramilitaries –

There are many things worth living for, a few things worth dying for, but nothing worth killing for.

16 People lost their lives in 1969

————————————————————

14 July 1969

Francis McCloskey, (67)

Catholic

Status: Civilian (Civ),

Killed by: Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC)

Died one day after being hit on head with batons during street disturbances, Dungiven, County Derry.

————————————————————

17 July 1969

Samuel Devenny, (42)

Catholic

Status: Civilian (Civ),

Killed by: Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC)

Died three months after being badly beaten in his home, William Street, Bogside, Derry. He was injured on 19 April 1969.

————————————————————

14 August 1969

John Gallagher, (30)

Catholic

Status: Civilian (Civ),

Killed by: Ulster Special Constabulary (USC)

Shot during street disturbances, Cathedral Road, Armagh.

————————————————————

14 August 1969

Patrick Rooney, (9)

Catholic

Status: Civilian (Civ),

Killed by: Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC)

Shot at his home, during nearby street disturbances, St Brendan’s Path, Divis Flats, Belfast.

————————————————————

15 August 1969

Herbert Roy, (26)

Protestant

Status: Civilian (Civ),

Killed by: non-specific Republican group (REP)

Shot while part of Loyalist crowd, during street disturbances, corner of Divis Street and Dover Street, Lower Falls, Belfast.

————————————————————

15 August 1969

Hugh McCabe, (20)

Catholic

Status: British Army (BA),

Killed by: Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC)

On leave. Shot during street disturbances while on the roof of Whitehall Block, Divis Flats, Belfast.

————————————————————

15 August 1969

Samuel McLarnon, (27)

Catholic

Status: Civilian (Civ),

Killed by: Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC)

Shot at his home during nearby street disturbances, Herbert Street, Ardoyne, Belfast.

————————————————————

15 August 1969

Michael Lynch, (28)

Catholic

Status: Civilian (Civ),

Killed by: Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC)

Shot during street disturbances, Butler Street, Ardoyne, Belfast.

————————————————————

15 August 1969

Gerald McAuley, (15)

Catholic

Status: Irish Republican Army Youth Section (IRAF),

Killed by: non-specific Loyalist group (LOY)

Shot during street disturbances, Bombay Street, Falls, Belfast.

————————————————————

15 August 1969

David Linton, (48)

Protestant

Status: Civilian (Civ),

Killed by: non-specific Republican group (REP)

Shot during street disturbances at the junction of Palmer Street and Crumlin Road, Belfast.

————————————————————

08 September 1969

John Todd, (29)

Protestant

Status: Civilian (Civ),

Killed by: non-specific Republican group (REP)

Shot during street disturbances, Alloa Street, Lower Oldpark, Belfast.

————————————————————

11 October 1969

George Dickie, (25)

Protestant

Status: Civilian (Civ),

Killed by: British Army (BA)

Shot during street disturbances, at the corner of Shankill Road and Downing Street, Belfast

————————————————————

11 October 1969

Herbert Hawe, (32)

Protestant

Status: Civilian (Civ),

Killed by: British Army (BA)

Shot during street disturbances, Hopeton Street, Shankill, Belfast.

————————————————————

11 October 1969

Victor Arbuckle, (29)

Protestant

Status: Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC),

Killed by: non-specific Loyalist group (LOY)

Shot during street disturbances, Shankill Road, Belfast.

————————————————————

21 October 1969

Thomas McDowell, (45)

Protestant

Status: Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF),

Killed by: Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF)

Died two days after being injured in premature bomb explosion at hydroelectric power station near Ballyshannon, County Donegal.

————————————————————

01 December 1969

Patrick Corry, (61)

Catholic

Status: Civilian (Civ),

Killed by: Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC)

Died four months after being hit on the head with batons, during altercation between local people and Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) patrol, Unity Flats, off Upper Library Street, Belfast. Injured on 2nd August 1969

————————————————————

Background

Northern Ireland was destabilised throughout 1968 by sporadic rioting arising out of the civil disobedience campaign of the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (NICRA), which was demanding an end to discrimination against Catholics in voting rights, housing and employment. NICRA was opposed by Ian Paisley‘s Ulster Constitution Defence Committee (UCDC) and other loyalist groups.

During the summer of 1969, before the riots broke out, the International Commission of Jurists (ICJ) published a highly critical report on the British government‘s policy in Northern Ireland. The Times wrote that this report “criticised the Northern Ireland Government for police brutality, religious discrimination [against Catholics] and gerrymandering in politics”.[4] The ICJ secretary general said that laws and conditions in Northern Ireland had been cited by the South African government “to justify their own policies of discrimination” (see South Africa under apartheid).[4] The Times also reported that the Ulster Special Constabulary (USC), Northern Ireland’s reserve police force, was “regarded as the militant arm of the Protestant Orange Order“.[4] The Belfast Telegraph reported that the ICJ had added Northern Ireland to the list of states/jurisdictions “where the protection of human rights is inadequately assured”.[5]

Events leading up to the August riots

The first major confrontation between Civil Rights activists and the police occurred in Derry on 5 October 1968, when a NICRA march was baton-charged by the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) police.[6] Disturbed by the prospect of major violence, the Prime Minister of Northern Ireland, Terence O’Neill, promised reforms in return for a “truce”, whereby no further demonstrations would be held.

However the truce was broken in January 1969 when People’s Democracy, a radical left-wing group, staged an anti-government march from Belfast to Derry. Loyalists attacked the marchers a number of times, most determinedly at Burntollet Bridge (about five miles (8 km) outside Derry), and the RUC were accused of not protecting the marchers. This action, and the RUC’s subsequent entry into the Bogside, led to serious rioting in Derry.[7]

In March and April 1969, there were six bomb attacks on electricity and water infrastructure targets, causing blackouts and water shortages. At first the attacks were blamed on the Irish Republican Army (IRA). In fact, it later emerged that members of the loyalist Ulster Protestant Volunteers (UPV) and Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) had carried out the bombings in an attempt to implicate the IRA, destabilise the Government and halt the reforms demanded by the Civil Rights movement and promised by Terence O’Neill.[7]

There was some movement on reform in Northern Ireland in the first half of 1969. On 23 April the Unionist Parliamentary Party voted by 28 to 22 to introduce universal adult suffrage in local government elections in Northern Ireland. The call for “one man, one vote” had been one of the key demands of the civil rights movement.[7] Five days later, Terence O’Neill resigned as UUP leader and Northern Ireland Prime Minister and was replaced in both roles by James Chichester-Clark. Chichester-Clark, despite having resigned in protest over the introduction of universal suffrage in local government, announced that he would continue the reforms begun by O’Neill.[7]

Street violence, however, continued to escalate. On 19 April there was serious rioting in the Bogside area of Derry following clashes between NICRA marchers, loyalists and the RUC. A Catholic, Samuel Devenny was severely beaten by the RUC and later died of his injuries.[7][8] On 12 July, during the Orange Order‘s Twelfth of July marches, there was serious rioting in Derry, Belfast and Dungiven, causing many families in Belfast to flee from their homes.[7] A Catholic civilian Francis McCloskey (67) died one day after being hit on the head with batons by RUC officers during rioting in Dungiven.[7][8]

Battle of the Bogside

See Battle of Bogside

Sporadic violence took place throughout the rest of the year between Catholic nationalists, Protestant loyalists and the RUC, and intensified over the summer, during the Orange Order‘s marching season. On 2 August, there was serious rioting in Belfast, when Protestant crowds from the Crumlin Road area tried to storm the Catholic Unity Flats. They were held back with difficulty by the police.

This unrest culminated in a pitched battle in Derry from 12–15 August. The Battle of the Bogside began when violence broke out around a loyalist Apprentice Boys of Derry parade on 12 August. The RUC, in trying to disperse the nationalist crowd, drove them back into the nationalist Bogside area and then tried to enter the area themselves. The Bogside’s inhabitants mobilised en masse to prevent them entering the area and a huge riot ensued between hundreds of RUC personnel and thousands of Bogsiders. On the second day of this confrontation, 13 August, the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association appealed for demonstrations across Northern Ireland in support of the Bogside, in an effort to draw off police resources from the conflict there. When nationalists elsewhere in Northern Ireland carried out such demonstrations, severe inter-communal violence erupted between Catholics, Protestants and the police.

Rioting in Belfast

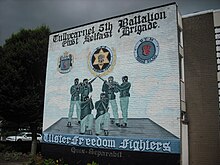

A mural in Belfast remembering the 1969 riots

Belfast saw by far the most intense violence of the August 1969 riots. Unlike Derry, where Catholic nationalists were a majority, in Belfast they were a minority and were also geographically divided and surrounded by Protestants and loyalists.[9] For this reason, whereas in Derry the fighting was largely between nationalists and the RUC, in Belfast it also involved fighting between Catholics and Protestants, including exchanges of gunfire and widespread burning of homes and businesses.[10]

On the night of 12 August, bands of Apprentice Boys arrived back in Belfast after taking part in the Derry march. They were met by Protestant pipe bands and a large crowd of supporters. They then marched to Shankill Road waving Union Flags and singing “The Sash My Father Wore” (a popular loyalist ballad).[9]

According to journalists Patrick Bishop and Eamonn Mallie, “Both communities were in the grip of a mounting paranoia about the other’s intentions. Catholics were convinced that they were about to become victims of a Protestant pogrom; Protestants that they were on the eve of an IRA insurrection”.[11]

Wednesday 13 August

The first disturbances in Northern Ireland’s capital took place on the night of 13 August. Derry activists Eamonn McCann and Sean Keenan contacted Frank Gogarty of the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association to organise demonstrations in Belfast to draw off police from Derry.[12] Independently, Belfast IRA leader Billy McMillen ordered republicans to organise demonstrations, “in support of Derry”.[13]

In protest at the RUC’s actions in Derry, a group of 500 nationalists and republicans assembled at Divis flats and staged a rally outside Springfield Road RUC station, where they handed in a petition.[14]

After handing in the petition, the crowd of 1–2000 people, including IRA members such as Joe McCann,[15] began a protest march along Falls Road and Divis Street to the Hastings Street RUC base.[14] When they arrived, about 50 youths broke away from the march and attacked the RUC base with stones and petrol bombs.[14][16] The RUC responded by sending out riot police[14] and by driving Shorland armoured cars at the crowd.[16] Protesters pushed burning cars onto the road to stop the RUC from entering the nationalist area.[9]

At Leeson Street, roughly halfway between the clashes at Springfield and Hastings Street RUC bases, an RUC Humber armoured car was attacked with a hand grenade and rifle fire.[16][17] At the time, it was not known who had launched the attack, but it has since emerged that it was IRA members, acting under the orders of Billy McMillen. McMillen also authorised members of the Fianna (IRA youth wing) to petrol bomb the Springfield Road RUC base.[15] Shots were exchanged there between the IRA and RUC.[16]

In addition to the attacks on the RUC, the car dealership of Protestant Isaac Agnew, on the Falls Road, was destroyed. The nationalist crowd also burnt a Catholic-owned pub and betting shop.[18] At this stage, loyalist crowds gathered on the Shankill Road but did not join in the fighting.[19]

That night barricades went up at the interface areas between Catholic and Protestant neighbourhoods.

A Shorland armoured car. The RUC used Shorlands mounted with Browning heavy machine-guns during the riots

Thursday 14 August and early hours of Friday 15 August

On 14 August, many Catholics and Protestants living on the edge of their ghettos fled their homes for safety.[9]

The loyalists viewed the nationalist attacks of Wednesday night as an organised attempt by the IRA “to undermine the constitutional position of Northern Ireland within the United Kingdom”.[17]

The IRA, contrary to loyalist belief, was responding to events rather than orchestrating them. Billy McMillen called up all available IRA members for “defensive duties” and sent parties out to Cupar Street, Divis Street and St Comgall’s School on Dover Street. They amounted to 30 IRA Volunteers, 12 women, 40 youths from the Fianna and 15–20 girls. Their arms consisted of one Thompson submachine gun, one Sten submachine gun, one Lee–Enfield rifle and six handguns. A “wee factory” was also set up in Leeson Street to make petrol bombs.[20] Their orders at the outset were to, “disperse people trying to burn houses, but under no circumstances to take life”.[21]

Falls–Shankill interface near Divis Tower

That evening, a nationalist crowd marched to Hastings Street RUC station, which they began to attack with stones for a second night.[22] Loyalist crowds (wielding petrol bombs, bricks, stones, sharpened poles and protective dustbin lids) gathered at neighbouring Dover and Percy Streets.[23] They were confronted by nationalists, who had hastily blocked their streets with barricades. Fighting broke out between the rival factions at about 11:00 pm.[24] The RUC concentrated their efforts on the nationalist rioters, who they scattered with armoured cars.[9] Catholics claimed that USC officers had been seen giving guns to the loyalists,[9] while journalists reported seeing pike-wielding loyalists standing among the RUC officers.[25]

From the nearby rooftop of Divis Tower flats, a group of nationalists would spend the rest of the night raining missiles on the RUC below.[9] A chain of people were passing stones and petrol bombs from the ground to the roof.[26]

Loyalists began pushing into the Falls Road area along Percy Street, Beverly Street and Dover Street. The rioters contained a rowdy gang of loyalist football supporters who had returned from a match.[27] On Dover Street, the loyalist crowd was led by Ulster Unionist Party MP John McQuade.[28] On Percy Street, a loyalist opened fire with a shotgun,[23] and USC officers helped the loyalists to push back the nationalists.[17] As they entered the nationalist ghetto, loyalists began burning Catholic homes and businesses on Percy Street, Beverly Street and Dover Street.

Divis came under heavy machine-gun fire from the RUC, killing two people

Memorial plaque to Patrick Rooney and Hugh McCabe

At the intersection of Dover and Divis Street, an IRA unit[29] opened fire on the crowd of RUC officers and loyalists, who were trying to enter the Catholic area. Protestant Herbert Roy (26) was killed[8] and three officers were wounded.[26] At this point, the RUC, believing they were facing an organised IRA uprising, deployed Shorland armoured cars mounted with heavy Browning machine guns,[17] whose .30 calibre bullets “tore through walls as if they were cardboard”.[30]

In response to the RUC coming under fire at Divis Street, three Shorland armoured cars were called to the scene. The Shorlands were immediately attacked with gunfire, an explosive device and petrol bombs. The RUC believed that the shots had come from nearby Divis Tower.[28] Gunners inside the Shorlands returned fire with their heavy machine-guns. At least thirteen Divis Tower flats were hit by high-velocity gunfire. A nine-year-old boy, Patrick Rooney, was killed by machine-gun fire as he lay in bed in one of the flats. He was the first child to be killed in the violence.[31]

At about 01:00, not long after the shooting of Patrick Rooney, the RUC again opened fire on Divis Tower. The shots killed Hugh McCabe (20), a Catholic soldier who was ‘on leave’.[8] He and another had been on the roof of the Whitehall building (which was part of the Divis complex) and were pulling a wounded man to safety. The RUC claimed he was armed at the time and that gunfire was coming from the roof, but this was denied by many witnesses.[32]

The Republican Labour Party MP for Belfast Central, Paddy Kennedy, who was on the scene, phoned the RUC headquarters and appealed to Northern Ireland Minister for Home Affairs, Robert Porter, for the Shorlands to be withdrawn and the shooting to stop. Porter replied that this was impossible as, “the whole town is in rebellion”. Porter told Kennedy that Donegall Street police station was under heavy machine-gun fire. In fact, it was undisturbed throughout the riots.[33]

Some time after the killing of Hugh McCabe, some 200 loyalists attacked Catholic Divis Street and began burning houses there.[34] A unit of six IRA volunteers in St Comgall’s School shot at them with a rifle, a thompson machine-gun and some pistols; keeping the attackers back and wounding eight of them.[35] An RUC Shorland then arrived and opened fire on the school.[34] The IRA gunmen returned fire and managed to escape.[17]

Falls–Shankill interface near Clonard Monastery

West of St Comgall’s, loyalists broke through the nationalist barricades on Conway Street and burned two-thirds of the houses. Catholics claimed that the RUC held them back so that the loyalists could burn their homes.[34] The Scarman Report found that RUC officers were on Conway Street when its houses were set alight, but “failed to take effective action”.[17] Journalist Max Hastings wrote that loyalists on Conway Street had been begging the RUC to give them their guns.[34]

Ardoyne

Rioting in Ardoyne, north of the city centre, began in the evening near Holy Cross Catholic church. Loyalists crossed over to the Catholic/nationalist side of Crumlin Road to attack Brookfield Street, Herbert Street, Butler Street and Hooker Street. These had been hastily blocked by nationalist barricades.[9] Loyalists reportedly threw petrol bombs at Catholics “over the heads of RUC officers”,[36] as RUC armoured cars were used to smash through the barricades.[37]

The IRA had little presence in Ardoyne and its defence was organised by a group of ex-servicemen armed with shotguns.[37]

The nationalist gunmen fired the first shots at the RUC, who responded by firing machine-guns down the streets, killing two Catholic civilians (Samuel McLarnon, 27, and Michael Lynch, 28) and wounding ten more.[8][38]

Friday 15 August

The morning of 15 August saw many Catholic families in central Belfast flee to Andersonstown on the western fringes of the city, to escape the rioting. According to Bishop and Mallie, “Each side’s perceptions of the other’s intentions had become so warped that the Protestants believed the Catholics were clearing the decks for a further attempt at insurrection in the evening”.[39]

At 04:30 on Friday 15 August, the Police Commissioner for Belfast asked for military aid.[40] From the early hours of Friday, the RUC had withdrawn to its bases to defend them. The interface areas were thus left unpoliced for half a day until the British Army arrived.[40] The Deputy Police Commissioner had assumed that the British Army would be deployed by 10:00 or 11:00.[40] At 12:25 that afternoon, the Northern Ireland cabinet finally sent a request for military aid to the Home Office in London.[40] However, it would be another nine hours until the British Army arrived at the Falls/Shankill interface where it was needed. Many Catholics and nationalists felt that they had been left at the mercy of loyalists by forces of the state who were meant to protect them.[40]

The IRA, which had limited manpower and weaponry at the start of the riots, was also exhausted and low on ammunition. Its leader Billy McMillen and 19 other republicans were arrested by the RUC early on 15 August under the Special Powers Act.[41]

There was fierce rioting in streets around Clonard Monastery (pictured), where hundreds of Catholic homes were burned

Falls–Shankill interface near Clonard Monastery

On 15 August, violence continued along the Falls/Shankill interface. Father PJ Egan of Clonard Monastery recalled that a large loyalist mob moved down Cupar Street at about 15:00 and was held back by nationalist youths.[42] Shooting began at about 15:45.[40] Egan claimed that himself and other priests at Clonard Monastery made at least four calls to the RUC for help, but none came.[42]

A small IRA party under Billy McKee was present and had two .22 rifles at their disposal. They exchanged shots with a loyalist sniper who was firing from a house on Cupar Street, but failed to dislodge him, or to halt the burning of Catholic houses in the area.[9][43] Almost all of the houses on Bombay street were burned by the loyalists, and many others were burned on Kashmir Road and Cupar Street – the most extensive destruction of property during the riots.[44]

A loyalist sniper shot dead Gerald McAuley (15), a member of the Fianna (IRA’s youth wing),[8] as he helped people flee their homes on Bombay Street.[45]

At about 18:30 the British Army’s The Royal Regiment of Wales was deployed on the Falls Road.[17][40] where they were greeted with subdued applause and cheering.[9] However, despite pleas from locals, they did not move into the streets that were being attacked.[40] At about 21:35 that night, the soldiers finally took up positions at the blazing interface[40] and blocked the streets with barbed-wire barricades. Father PJ Egan recalled that the soldiers called on the loyalists to surrender but they instead began shooting and throwing petrol bombs at the soldiers.[42] The soldiers could only fire back on the orders of an officer when life was directly threatened.[46] The loyalists continued shooting and burned more Catholic-owned houses on Bombay Street,[17] but were stopped by soldiers using tear gas.[9]

Ardoyne

British soldiers were not deployed in Ardoyne, and violence continued there on Friday night. Nationalists hijacked 50 buses from the local bus depot, set them on fire and used them as makeshift barricades to block access to Ardoyne. According to republican activist Martin Meehan, 20 Catholics were wounded by shotgun fire that night.[citation needed] A Protestant civilian, David Linton (48), was shot dead by nationalist gunmen at the Palmer Street/Crumlin Road junction.[8] Several Catholic-owned houses were set alight on Brookfield Street.[17] The Scarman Report found that an RUC armoured vehicle was nearby when Brookfield Street was set alight, but made no move.[17]

Saturday 16 August

On the evening of 16 August the British Army was deployed on Crumlin Road. Thereafter, the violence died down into what the Scarman report called, “the quiet of exhaustion”.[17]

Disturbances elsewhere

Towns and cities where major riots took place

In aid of the Bogsiders, the NICRA executive decided to launch protests in towns across Northern Ireland.[17] The Scarman Report concluded that the spread of the disturbances “owed much to a deliberate decision by some minority groups to relieve police pressure on the rioters in Londonderry”. It included the NICRA among these groups.[17]

On the evening of 11 August a riot erupted in Dungannon after a meeting of the NICRA. This was quelled after the RUC baton charged nationalist rioters down Irish Street. There were claims of police brutality.[17]

On 12 August, protesters attacked the RUC bases in Coalisland, Strabane and Newry.[47]

On 13 August there were further riots in Dungannon, Coalisland, Dungiven, Armagh and Newry.[17] In Coalisland, USC officers opened fire on rioters without orders but were immediately ordered to stop.[17]

On 14 August riots continued in Dungannon, Armagh and Newry. In Dungannon and Armagh, USC officers again opened fire on rioters. They fired 24 shots on Armagh’s Cathedral Road, killing Catholic civilian John Gallagher and wounding two others.[17][48] In Newry, nationalist rioters surrounded the RUC station and attacked it with petrol bombs. In Crossmaglen on 17 August, the RUC station was attacked with petrol bombs and three hand grenades.[citation needed]

Reactions

![[icon]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/1c/Wiki_letter_w_cropped.svg/20px-Wiki_letter_w_cropped.svg.png) |

This section requires expansion. (January 2011) |

- On 13 August, Taoiseach Jack Lynch made a television address in which he stated that the Irish Defence Forces would set up “field hospitals” along the border. He went on to say:

It is evident that the Stormont Government is no longer in control of the situation. Indeed the present situation is the inevitable outcome of the policies pursued for decades by successive Stormont Governments. It is clear, also, that the Irish Government can no longer stand by and see innocent people injured and perhaps worse.[7]

- On 14 August, Northern Ireland Prime Minister James Chichester-Clark stated in the House of Commons:

This is not the agitation of a minority seeking by lawful means the assertion of political rights. It is the conspiracy of forces seeking to overthrow a Government democratically elected by a large majority. What the teenage hooligans seek beyond cheap kicks I do not know. But of this I am quite certain – they are being manipulated and encouraged by those who seek to discredit and overthrow this Government”.[17]

- On 23 August Cardinal William Conway, together with the Bishops of Derry, Clogher, Dromore, Kilmore, and Down & Connor, issued a statement which included the following:

The fact is that on Thursday and Friday of last week the Catholic districts of Falls and Ardoyne were invaded by mobs equipped with machine-guns and other firearms. A community which was virtually defenceless was swept by gunfire and streets of Catholic homes were systematically set on fire. We entirely reject the hypothesis that the origin of last week’s tragedy was an armed insurrection.[7]

Effects

The rioting petered out by Sunday, 17 August. By the end of the riots:

- 8 people had been killed, including[8]

- 5 Catholics shot dead by the RUC

- 2 Protestants shot dead by nationalist gunmen

- 1 Fianna member shot dead by loyalist gunmen

- 750+ people had been injured[49] – 133 (72 Catholics and 61 Protestants) of those injured suffered gunshot wounds[49]

- 150+ Catholic homes[50] and 275+ businesses had been destroyed – 83% of all buildings destroyed were owned by Catholics[49]

During July, August and September 1969, 1,820+ families had been forced to flee their homes, including[51]

- 1,505 Catholic families

- 315 Protestant families

Catholics generally fled across the border into the Republic of Ireland, while Protestants generally fled to east Belfast.[51] The Irish Defence Forces set up refugee camps in the Republic – at one point the Gormanston refugee camp held 6000 refugees from Northern Ireland.[51]

Long-term effects

The modern “peace line” at Bombay Street in Belfast, seen from the Irish Catholic/nationalist side. This is the view from the back of a house.

The August riots were the most sustained violence that Northern Ireland had seen since the early 1920s. Many Protestants, loyalists and unionists believed the violence showed the true face of the Northern Ireland Catholic civil rights movement – as a front for the IRA and armed insurrection. They had mixed feelings regarding the deployment of British Army troops into Northern Ireland. Eddie Kinner, a resident of Dover Street who would later join the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF), vividly recalled the troops marching down his street with fixed bayonets and steel helmets. He and his neighbours had felt at the time as if they were being invaded by their “own army”.[52] Catholics and nationalists, on the other hand, saw the riots (particularly in Belfast) as an assault on their community by loyalists and the forces of the state. The disturbances, taken together with the Battle of the Bogside, are often cited as the beginning of the Troubles. Violence escalated sharply in Northern Ireland after these events, with the formation of new paramilitary groups on either side, most notably the Provisional Irish Republican Army in December of that year. On the loyalist side, the UVF (formed in 1966) were galvanised by the August riots and in 1971, another paramilitary group, the Ulster Defence Association was founded out of a coalition of loyalist militants who had been active since August 1969. The largest of these were the Woodvale Defence Association, led by Charles Harding Smith, and the Shankill Defence Association, led by John McKeague, which had been responsible for what organisation there was of loyalist violence in the riots of August 1969. While the thousands of British Army troops sent to Northern Ireland were initially seen as a neutral force, they quickly got dragged into the street violence and by 1971 were devoting most of their attention to combatting republican paramilitaries.

The Irish Republican Army

The role of the IRA in the riots has long been disputed. At the time, the organisation was blamed by the Northern Ireland authorities for the violence. However, it was very badly prepared to defend nationalist areas of Belfast, having few weapons or fighters on the ground.

The Scarman Inquiry, set up by the British government to investigate the causes of the riots, concluded:

Undoubtedly there was an IRA influence at work in the DCDA (Derry Citizens’ Defence Association) in Londonderry, in the Ardoyne and Falls Road areas of Belfast, and in Newry. But they did not start the riots, or plan them: indeed, the evidence is that the IRA was taken by surprise and did less than many of their supporters thought they should have done.[17]

In nationalist areas, the IRA was reportedly blamed for having failed to protect areas like Bombay Street and Ardoyne from being burned out. A Catholic priest, Fr Gillespie, reported that in Ardoyne the IRA was being derided in graffiti as “I Ran Away”.[53] However, IRA veterans of the time, who spoke to authors Brian Hanley and Scott Millar disputed this interpretation. One, Sean O’Hare, said, “I never saw it written on a wall. That wasn’t the attitude. People fell in behind the IRA, stood behind them 100%. Another, Sean Curry recalled, “some people were a bit angry but most praised the people who did defend the area. They knew that if the men weren’t there, the area wouldn’t have been defended.”[54]

At the time, the IRA released a statement on 18 August, saying, it had been, “in action in Belfast and Derry” and “fully equipped units had been sent to the border”. It had been, “reluctantly compelled into action by Orange murder gangs” and warned the British Army that if it, “was used to supress [sic] the legitimate demands of the people they will have to take the consequences” and urged the Irish government to send the Irish Army over the border.[55]

Cathal Goulding, the IRA Chief of Staff, sent small units from Dublin, Cork and Kerry to border counties of Donegal, Leitrim and Monaghan, with orders to attack RUC posts in Northern Ireland and draw off pressure from Belfast and Derry. A total of 96 weapons and 12,000 rounds of ammunition were also sent to the North.[56]

Nevertheless, the poor state of IRA arms and military capability in August 1969 led to a bitter split in the IRA in Belfast. According to Hanley and Millar, “dissensions that pre-dated August [1969] had been given a powerful emotional focus”.[57] In September 1969, a group of IRA men led by Billy McKee and Joe Cahill stated that they would no longer be taking orders from the Dublin leadership of the IRA, or from Billy McMillen (their commander in Belfast) because they had not provided enough weapons or planning to defend nationalist areas. In December 1969, they broke away to form the Provisional IRA and vowed to defend areas from attack by loyalists and the RUC. The other wing of the IRA became known as the Official IRA. Shortly after its formation, the Provisional IRA launched an offensive campaign against the state of Northern Ireland.

The RUC and USC

The actions of the RUC in the August 1969 riots are perhaps the most contentious issue arising out of the disturbances. Nationalists argue that the RUC acted in a blatantly biased manner, helping loyalists who were assaulting Catholic neighbourhoods. There were also strong suggestions that police knew when loyalist attacks were to happen and seemed to disappear from some Catholic areas shortly before loyalist mobs attacked.[49] This perception discredited the police in the eyes of many nationalists and later allowed the IRA to effectively take over policing in nationalist areas. In his study, From Civil Rights to Armalites, nationalist author Niall Ó Dochartaigh argues that the actions of the RUC and USC were the key factor in the worsening of the conflict. He wrote:

From the outset, the response of the state and its forces of law and order to Catholic mobilisation was an issue capable of arousing far more anger and activism than the issues around which mobilisation had begun. Police behaviour and their interaction with loyalist protesters probably did more to politically mobilise large sections of the Catholic community than did any of the other grievances.[58]

The Scarman Inquiry found that the RUC were “seriously at fault” on at least six occasions during the rioting. Specifically, they criticised the RUC’s use of Browning heavy machine-guns in built-up areas, their failure to stop Protestants from burning down Catholic homes, and their withdrawal from the streets long before the Army arrived. However, the Scarman Report concluded that, “Undoubtedly mistakes were made and certain individual officers acted wrongly on occasions. But the general case of a partisan force co-operating with Protestant crowds to attack Catholic people is devoid of substance, and we reject it utterly”.[17] The report argued that the RUC were under-strength, poorly led and that their conduct in the riots was explained by their perception that they were dealing with a co-ordinated IRA uprising. They pointed to the RUC’s dispersal of loyalist rioters in Belfast on 2–4 August in support of the force’s impartiality.

Of the B-Specials (Ulster Special Constabulary or USC), the Scarman Report said:

There were grave objections, well understood by those in authority, to the use of the USC in communal disturbances. In 1969 the USC contained no Catholics but was a force drawn from the Protestant section of the community. Totally distrusted by the Catholics, who saw them as the strong arm of the Protestant ascendancy, they could not show themselves in a Catholic area without heightening tension. Moreover they were neither trained nor equipped for riot control duty.[17]

The report found that the Specials had fired on Catholic demonstrators in Dungiven, Coalisland, Dungannon and Armagh, causing casualties, which, “was a reckless and irresponsible thing to do”. It found that USC officers had, on occasion, sided with loyalists mobs. There were reports that USC officers were spotted hiding among loyalist mobs, using coats to hide their uniforms.[49] Nevertheless, the Scarman Report concluded, “there are no grounds for singling out mobilised USC as being guilty of misconduct”.[17]

![]() listen); 26 January 1918[2] – 25 December 1989) was a Romanian Communist politician. He was General Secretary of the Romanian Communist Party from 1965 to 1989, and as such was the country’s second and last Communist leader. He was also the country’s head of state from 1967 to 1989.

listen); 26 January 1918[2] – 25 December 1989) was a Romanian Communist politician. He was General Secretary of the Romanian Communist Party from 1965 to 1989, and as such was the country’s second and last Communist leader. He was also the country’s head of state from 1967 to 1989.

![]() audio (help·info); c. 1942 – 20 October 2011), commonly known as Colonel Gaddafi,[b] was a Libyan revolutionary and politician who governed Libya as its primary leader from 1969 to 2011. Taking power in a coup d’etat, he ruled as Revolutionary Chairman of the Libyan Arab Republic from 1969 to 1977 and then as the “Brotherly Leader” of the Great Socialist People’s Libyan Arab Jamahiriya from 1977 to 2011, when he was ousted in the Libyan Civil War. Initially developing his own variant of Arab nationalism and Arab socialism known as the Third International Theory, he later embraced Pan-Africanism and served as Chairperson of the African Union from 2009 to 2010.

audio (help·info); c. 1942 – 20 October 2011), commonly known as Colonel Gaddafi,[b] was a Libyan revolutionary and politician who governed Libya as its primary leader from 1969 to 2011. Taking power in a coup d’etat, he ruled as Revolutionary Chairman of the Libyan Arab Republic from 1969 to 1977 and then as the “Brotherly Leader” of the Great Socialist People’s Libyan Arab Jamahiriya from 1977 to 2011, when he was ousted in the Libyan Civil War. Initially developing his own variant of Arab nationalism and Arab socialism known as the Third International Theory, he later embraced Pan-Africanism and served as Chairperson of the African Union from 2009 to 2010.