Source: Birmingham Pub Bombings – 21 November, 1974

Category Archives: Major events in The Troubles

The London Docklands bombing – 9 February 1996

Docklands bombing

1996

The London Docklands bombing (also known as the Canary Wharf bombing or South Quay bombing) occurred on 9 February 1996, when the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) detonated a powerful truck bomb in Canary Wharf, one of the two financial districts of London. The blast devastated a wide area and caused an estimated £100 million worth of damage. Although the IRA had sent warnings 90 minutes beforehand, the area was not fully evacuated; two people were killed and 39 were injured.

———————————————-

IRA bombs Canary Wharf, London

———————————————-

It marked an end to the IRA’s seventeen-month ceasefire. The IRA had agreed to a ceasefire in August 1994, on the understanding that Sinn Féin would be allowed to take part in peace negotiations. However, when the British government then demanded the IRA must fully disarm before any negotiations, the IRA resumed its campaign. After the bombing, the British government dropped its demand for the IRA to disarm before any negotiations

Background and planning

Since the beginning of its campaign in the early 1970s, the IRA had carried out many bomb attacks in England. As well as attacking military and political targets, it also bombed infrastructure and commercial targets. The goal was to damage the economy and cause disruption, which would put pressure on the British government to negotiate a withdrawal from Northern Ireland.[1] In the early 1990s, the IRA began another major bombing campaign in England. In February 1991 it launched a mortar attack on 10 Downing Street, headquarters of the British government, while Prime Minister John Major was holding a meeting. The mortars narrowly missed the building and there were no casualties. In April 1992, the IRA detonated a powerful truck bomb at the Baltic Exchange in the City of London, its main financial district. The blast killed three people and caused £800 million worth of damage; more than the total damage caused by all IRA bombings before it.[2] In November 1992, the IRA planted a large van bomb at Canary Wharf, London’s second financial district. However, security guards immediately alerted the police and the bomb was defused.[3] In April 1993 the IRA detonated another powerful truck bomb in the City of London. It killed one person and caused £500 million worth of damage.

In December 1993 the British and Irish governments issued the Downing Street Declaration. It allowed Sinn Féin, the political party associated with the IRA, to participate in all-party peace negotiations on condition that the IRA called a ceasefire. The IRA called a ceasefire on 31 August 1994. Over the next seventeen months there were a number of meetings between representatives of the British government and Sinn Féin. There were also talks—among the British and Irish governments and the Northern Ireland parties—about how all-party peace negotiations could take place.

By 1996, John Major’s government had lost its majority in the British parliament and was depending on Ulster unionist votes to stay in power. It was accused of pro-unionist bias as a result. The British government began insisting that the IRA must fully disarm before Sinn Féin would be allowed to take part in full-fledged peace talks. The IRA rejected this, seeing it as a demand for total surrender.[4] Sinn Féin said that the IRA would not disarm before talks, but that it would discuss disarmament as part of an overall solution. On 23 January 1996, the international commission for disarmament in Northern Ireland recommended that Britain drop its demand, suggesting that disarmament begin during talks rather than before.[5] The British government refused to drop its demand.

The bombing

At about 19:01 on 9 February, the IRA detonated a large bomb containing 500 kg of ammonium nitrate fertilizer and sugar,[4][6] in a small lorry about 80 yards (70 m) from South Quay Station on the Docklands Light Railway (in the Canary Wharf area of London), directly under the point where the tracks cross Marsh Wall.[7] The detonating cord was made of semtex, PETN and RDX high explosives.[4] The IRA had sent telephoned warnings 90 minutes beforehand, and the area was evacuated. However, two men working in the newsagents shop directly opposite the explosion, Inam Bashir (29) and John Jeffries (31), had not been evacuated in time and were killed in the explosion. 39 people required hospital treatment due to blast injuries and falling glass. Part of the South Quay Plaza was destroyed.[7] The explosion left a crater ten metres wide and three metres deep.[4] The shockwave from the blast caused windows as far east as Barking, approximately five miles away, to rattle.

————

Victims

————

—————————————

09 February 1996

Inan Ul-Haq Bashir, (29)

nfNIB

Status: Civilian (Civ),

Killed by: Irish Republican Army (IRA)

Killed in lorry bomb explosion, left in car park, South Quay railway station, Isle of Dogs, London. Inadequate warning given.

—————————————

09 February 1996

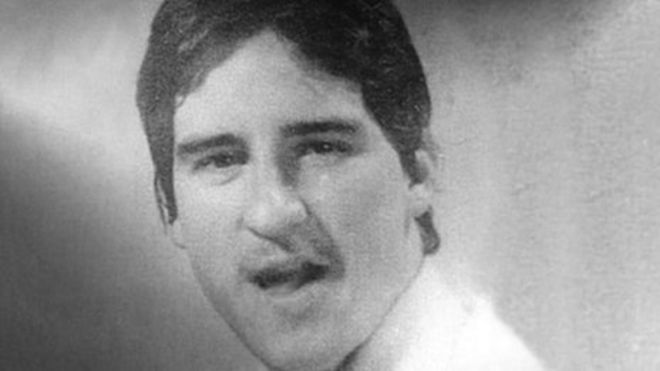

John Jefferies, (31)

nfNIB

Status: Civilian (Civ),

Killed by: Irish Republican Army (IRA)

Killed in lorry bomb explosion, left in car park, South Quay railway station, Isle of Dogs, London. Inadequate warning given.

—————————————

Approximately £100 million worth of damage was done by the blast.[4] Three nearby buildings (the Midland Bank building, South Quay Plaza I and II) were severely damaged (the latter two requiring complete rebuilding whilst the former was beyond economic repair and was demolished). The station itself was extensively damaged, but both it and the bridge under which the bomb was exploded were reopened within weeks (on 22 April), the latter requiring only cosmetic repairs despite its proximity to the blast.

This bomb represented the end to the IRA ceasefire during the Northern Ireland peace process at the time. James McArdle was convicted of conspiracy to cause explosions, and sentenced to 25 years in prison, but murder charges were dropped.[citation needed] McArdle was released under the terms of the Good Friday Agreement in June 2000 with a royal prerogative of mercy from Queen Elizabeth II.[8]

The IRA described the deaths and injuries as a result of the bomb as “regrettable”, but said that they could have been avoided if police had responded promptly to “clear and specific warnings”. Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police Sir Paul Condon said: “It would be unfair to describe this as a failure of security. It was a failure of humanity.”[9]

On 28 February, John Major, the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, and John Bruton, the Taoiseach of the Republic of Ireland, announced that all-party talks would be resumed in June. Major’s decision to drop the demand for IRA decommissioning of weapons before Sinn Fein would be allowed into talks led to criticism from the press, which accused him of being “bombed to the table”.[10]

My blog and Twitter account are dedicated to remembering all innocent victims of the Northern Ireland Troubles and all those killed by terrorists across the globe. Have a little look around , you might find something of interest.

Please take the time to follow me on Twitter @bfchild66 and sign up for my blog by clicking the follow button at the bottom of this page , or any page for that matter.

Take Care and be safe!

IRA Mortar Attack on Downing Street

Downing Street mortar attack

7th February 1991

—————————-

IRA mortar 10 Downing Street

—————————-

The Downing Street mortar attack was carried out by the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) on 10 Downing Street, London, the official residence of the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. The 7 February 1991 attack, an assassination attempt on John Major and his War Cabinet who were meeting to discuss the Gulf War, was originally planned to target Major’s predecessor Margaret Thatcher. Two shells overshot Downing Street and failed to explode, and one shell exploded in the rear garden of number 10. No members of the cabinet were injured, though four other people received minor injuries, including two police officers.

Background

During the Troubles, as part of its armed campaign against British rule in Northern Ireland, the Provisional IRA had repeatedly used homemade mortars against targets in Northern Ireland.[1][2] The most notable attack was the 1985 Newry mortar attack which killed nine members of the Royal Ulster Constabulary.[1][2] The IRA had not previously used mortars in England, but in December 1988 items used in their construction and technical details regarding the weapon’s trajectory were found during a raid in Battersea, South London conducted by members of the Metropolitan Police Anti-Terrorist Branch.[3][4] In the late 1980s British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher was top of the IRA’s list for assassination, following the failed attempt on her life in the Brighton hotel bombing.[3] Security around Downing Street had been increased at a cost of £800,000 following increased IRA activity in England in 1988, including the addition of a police guard post and security gates at the end of the street.[5][6] Plans to leave a car bomb on a street near Downing Street and detonate it by remote control as Thatcher’s official car was driving by had been ruled out by the IRA’s Army Council owing to the likelihood of civilian casualties, which some Army Council members argued would have been politically counter-productive.[3]

Preparation

The Army Council instead sanctioned a mortar attack on Downing Street, and in mid-1990 two IRA members travelled to London to plan the attack.[3] One of the IRA members was knowledgeable about the trajectory of mortars and the other, from the IRA’s Belfast Brigade, was familiar with their manufacture.[3] An active service unit purchased a Ford Transit van and rented a garage, and an IRA co-ordinator procured the explosives and materials needed to manufacture the mortars.[3] The IRA unit began constructing the mortars and cutting a hole in the roof of the van for the mortars to be fired through, and reconnoitred locations in Whitehall to find a suitable place from which the mortars could be fired at the rear of 10 Downing Street, the Prime Minister’s official residence and office.[3][5] Once preparations were complete the two IRA members returned to Ireland, as the IRA leadership considered them to be valuable personnel and did not wish to risk them being arrested in any follow-up operation by the security services.[3] In November 1990 Margaret Thatcher unexpectedly resigned from office, but the Army Council decided the planned attack should still go ahead, targeting her successor John Major.[5] The IRA planned to attack when Major and his ministers were likely to be meeting at Downing Street, and waited until the date of a planned cabinet meeting was publicly known.[7]

The attack

———————-

IRA Mortar Attack on 10 Downing Street

———————-

On the morning of 7 February 1991, the War Cabinet and senior government and military officials were meeting at Downing Street to discuss the ongoing Gulf War. As well as the Prime Minister, John Major, those present at the meeting included politicians Douglas Hurd, Tom King, Norman Lamont, Peter Lilley, Patrick Mayhew, David Mellor and John Wakeham, civil servants Robin Butler, Percy Cradock, Gus O’Donnell and Charles Powell, and Chief of the Defence Staff David Craig.[5][8] As the meeting began an IRA member was driving the transit van to the launch site, at the junction of Horse Guards Avenue and Whitehall close to the headquarters of the Ministry of Defence, approximately 200 yards (200 m) from Downing Street,[2][7] amid a heavy snowfall.[9]

On arrival, the driver parked the van and left the scene on a waiting motorcycle.[7] Several minutes later at 10:08 am, as a policeman was walking towards the van to investigate it, three mortar shells were launched, followed by the explosion of a pre-set incendiary device. This device was designed to destroy any forensic evidence and set the van on fire.[7] Each shell was four and a half feet long, weighed 140 pounds (60 kg), and carried a 40 pounds (20 kg) payload of the plastic explosive Semtex.[10] The type of device used by the attackers was a Mark 10 homemade mortar, according to the British designation.[11] Two shells landed on a grassed area near the Foreign and Commonwealth Office and failed to explode.[2][7] The third shell exploded in the rear garden of 10 Downing Street, 30 yards (30 m) from the office where the cabinet were meeting.[7][10] Had the shell struck 10 Downing Street itself, it is probable the entire cabinet would have been killed.[10][12] On hearing the explosion the cabinet ducked under the table for cover. Bomb-proof netting on the windows of the cabinet office muffled the force of the explosion, which also scorched the rear wall of the building and made a crater several feet deep in the garden.[13][2][3]

Once the sound of the explosion and aftershock had died down, John Major said, “I think we had better start again, somewhere else.”[14] The room was evacuated and the meeting reconvened less than ten minutes later in the Cobra Room.[13][2] No members of the cabinet were injured, but four people received minor injuries, including two police officers injured by flying debris.[3][9]

Reaction

The IRA claimed responsibility for the attack with a statement issued in Dublin, saying “Let the British government understand that, while nationalist people in the six counties [Northern Ireland] are forced to live under British rule, then the British Cabinet will be forced to meet in bunkers”.[13] John Major told the House of Commons that “Our determination to beat terrorism cannot be beaten by terrorism. The IRA’s record is one of failure in every respect, and that failure was demonstrated yet again today. It’s about time they learned that democracies cannot be intimidated by terrorism, and we treat them with contempt”.[13] Leader of the Opposition Neil Kinnock also condemned the attack, stating “The attack in Whitehall today was both vicious and futile”.[9] The head of the Metropolitan Police Anti-Terrorist Branch, Commander George Churchill-Coleman, described the attack as “daring, well planned, but badly executed”.[13] Peter Gurney, the head of the Explosives Section of the Anti-Terrorist Branch who defused one of the unexploded shells, gave his reaction to the attack:[10]

It was a remarkably good aim if you consider that the bomb was fired 250 yards [across Whitehall] with no direct line of sight. Technically, it was quite brilliant and I’m sure that many army crews, if given a similar task, would be very pleased to drop a bomb that close. You’ve got to park the launch vehicle in an area which is guarded by armed men and you’ve got less than a minute to do it. I was very, very surprised at how good it was. If the angle of fire had been moved about five or ten degrees, then those bombs would actually have impacted on Number Ten.[10]

A further statement from the IRA appeared in An Phoblacht, with a spokesperson stating “Like any colonialists, the members of the British establishment do not want the result of their occupation landing at their front or back doorstep … Are the members of the British cabinet prepared to give their lives to hold on to a colony? They should understand the cost will be great while Britain remains in Ireland.”[15] The attack was celebrated in Irish rebel popular culture when The Irish Brigade released a song titled “Downing Street”, to the tune of “On the Street Where You Live“, which included the lyrics “while you hold Ireland, it’s not safe down the street where you live

……………………………………………………………………

Sean Graham bookmakers’ shooting

Sean Graham bookmakers’ shooting

5 February 1992

On 5 February 1992, a mass shooting took place at the Sean Graham bookmaker‘s shop on the Lower Ormeau Road in Belfast, Northern Ireland. Members of the Ulster Defence Association (UDA), a loyalist paramilitary group, opened fire on the customers, killing five civilians and wounding another nine. The shop was in an Irish nationalist area, and all of the victims were local Catholic civilians. The UDA claimed responsibility using the cover name “Ulster Freedom Fighters”, and said the shooting was retaliation for the Teebane bombing, which had been carried out by the Provisional IRA less than three weeks before

Background

The start of 1992 had witnessed an intensification in the campaign of violence being carried out by the Ulster Defence Association (UDA) under their UFF covername. The group’s first killing that year was on 9 January when Catholic civilian Phillip Campbell was shot dead at his place of work near Moira by a Lisburn-based UDA unit.[1] The same group killed another Catholic civilian, Paul Moran, at the end of the month and a few days later taxi driver Paddy Clarke was killed at his north Belfast home by members of the UDA West Belfast Brigade.[2]

However, the Inner Council of the UDA, which contained the six brigadiers that controlled the organisation, felt that these one-off killings were not sending a strong enough message to republicans and so it sanctioned a higher-profile attack in which a number of people would be killed at once.[2] On this basis the go-ahead was given to attack Sean Graham bookmaker’s shop on the Irish nationalist Lower Ormeau Road. This was a major arterial route in the city and was near the UDA stronghold of Annadale Flats.[2] According to David Lister and Hugh Jordan, the bookmaker’s shop was chosen by West Belfast Brigadier and Inner Council member Johnny Adair because he had strong personal ties with the commanders of the Annadale UDA.[3] A 1993 report commissioned by RUC Special Branch also claimed that Adair was the driving force behind the attack.[3]

The shooting

The attack occurred at 2:20 in the afternoon.[4] A car parked on University Avenue facing the bookmakers and two men, wearing boiler suits and balaclavas, left the car and crossed the Ormeau Road to the shop.[5] One was armed with a VZ.58 Czechoslovak semi-automatic rifle and the other with a 9mm pistol. They entered the shop—in which there were 15 customers—and opened fire, unleashing a total of 44 shots on the assembled victims.[6]

Five Catholic men and boys were killed: Christy Doherty (52), Jack Duffin (66), James Kennedy (15), Peter Magee (18) and William McManus (54).[7] Nine others were wounded, one critically.[4] Four of them died at the scene although 15-year-old Kennedy survived until he reached the hospital, his final words being reported as “tell my mummy that I love her”.[8] Kennedy’s mother Kathleen died two years later after becoming a recluse. Her husband, James (Sr.), blamed his wife’s death on the shooting by claiming “the bullets that killed James didn’t just travel in distance, they travelled in time. Some of those bullets never stopped travelling”.[8]

One of the wounded described the shooting to British journalist Peter Taylor:

“There was a right crowd in [the betting shop] and I cracked a joke with a couple of them – they were like that, always laughing and carrying on. I had only been in for about twenty or twenty-five minutes when the shooting started – I was standing next to the door with a docket in my hand studying the form. At first I thought it was a hold-up but then the shooting started and somebody yelled, ‘Hit the deck’. I just lay there and prayed that the shooting would stop. It seemed to go on for a lifetime. There wasn’t a sound for a few seconds – everybody was so stunned, but then the screaming started. People were yelling out in agony. You could hardly see anything. The room was full of gun smoke and the smell would have choked you”.[9]

In a separate incident, a unit of the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) had travelled to the area at the time of the attack with the intention of killing a local Sinn Féin activist based on intelligence they had received that he returned home about that time every day. The attack was abandoned, however, when the car carrying the UVF members was passed by speeding Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) vehicles and ambulances. The UVF members, who had already retrieved their weapons for the attack, were said to be livid with the UDA for not co-ordinating with them beforehand and effectively spoiling their chance to kill a leading local republican.[10]

—————————————————————————

The Victims

—————————————————————————

05 February 1992

Peter Magee, (18)

Catholic

Status: Civilian (Civ),

Killed by: Ulster Freedom Fighters (UFF)

Shot during gun attack on Sean Graham’s Bookmaker’s shop, Ormeau Road, Belfast

—————————————————————————

05 February 1992

Jack Duffin, (66)

Catholic

Status: Civilian (Civ),

Killed by: Ulster Freedom Fighters (UFF)

Shot during gun attack on Sean Graham’s Bookmaker’s shop, Ormeau Road, Belfast

—————————————————————————

05 February 1992

James Kennedy, (15)

Catholic

Status: Civilian (Civ),

Killed by: Ulster Freedom Fighters (UFF)

Shot during gun attack on Sean Graham’s Bookmaker’s shop, Ormeau Road, Belfast

—————————————————————————

05 February 1992

William McManus, (54)

Catholic

Status: Civilian (Civ),

Killed by: Ulster Freedom Fighters (UFF)

Shot during gun attack on Sean Graham’s Bookmaker’s shop, Ormeau Road, Belfast

—————————————————————————

05 February 1992

Christy Doherty, (52)

Catholic

Status: Civilian (Civ),

Killed by: Ulster Freedom Fighters (UFF)

Shot during gun attack on Sean Graham’s Bookmaker’s shop, Ormeau Road, Belfast

—————————————————————————

Aftermath

A UDA statement in the aftermath of the attack claimed that the killings were justified as the Lower Ormeau was “one of the IRA‘s most active areas”.[8] The statement also included the phrase “remember Teebane”, suggesting that they intended the killings as retaliation for the Teebane bombing in County Tyrone less than three weeks earlier. In that attack, the IRA had killed eight Protestant men who were repairing a British Army base.[11] The same statement had also been yelled by the gunmen as they ran from the betting shop.[8] Alex Kerr, who was then UDA Brigadier for South Belfast, released a second statement about a month after the attack in which he sought to justify the killings. Kerr stated that “the IRA was extremely active in the lower Ormeau and the nationalist population there shielded them. They paid the price for Teebane”. He added that if there were any further bombings like that at Teebane then the UDA would retaliate in the same way as at Sean Graham’s.[12]

See Teebane Bus Bomb

The idea that the killings were justified because of Teebane was shunned by Rev. Ivor Smith, a Presbyterian minister who was based in the area and who worked with the families of the bomb victims. He said that the UDA claim was “like a knife through the heart. We were absolutely appalled at the thought that somebody would try to do something like that and justify it by bringing in Teebane. As far as the families were concerned, it was very definitely not ‘in my name'”.[11] A letter expressing deep sympathy from Betty Gilchrist, a Protestant whose husband had been killed at Teebane, was read out at the funeral of Jack Duffin.[12] Alasdair McDonnell, a general practitioner and Social Democratic and Labour Party councillor in the area, also suggested that the attack had been in response to Teebane. However, he was strongly rebuked by the Lower Ormeau Residents Action Group, a residents’ association with Sinn Féin links, for seemingly justifying the killings with this claim.[13]

When a July 1992 Orange Order march passed the scene of the shooting, Orangemen shouted pro-UDA slogans and held aloft five fingers as a taunt to residents over the five deaths.[4][14] The claim is corroborated by Henry McDonald and Jim Cusack. The images of Orangemen and loyalist flute band members holding up five fingers as they passed the shop were beamed around the world and was a public relations disaster for the Order.[15] Patrick Mayhew, then Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, said that the actions of the marchers “would have disgraced a tribe of cannibals”.[14] The incident led to a more concerted effort by Lower Ormeau residents to have the marches banned from the area, which later succeeded.[15]

No one was ever convicted for the killings although, locally, blame fell on Joe Bratty and his sidekick Raymond Elder, the two leading UDA figures in the Annadale Flats.[12] McDonald and Cusack suggest that, whilst Bratty had been the brains behind the attack, the gunmen he had used were actually from East Belfast and that a UDA member later convicted of supplying one of the guns had been at the shooting.[12] Lister and Jordan, however, claim that one of the gunmen was actually from west Belfast and was supplied to Bratty by Adair.[3] Bratty was charged with involvement in the attack although the charges were withdrawn.[16] Following his release from custody, Adair organised a lavish celebration party for Bratty in Scotland where he allegedly gave Bratty a gold ring inscribed with the initials UFF.[3]

The IRA did not immediately retaliate although in a statement they claimed to know the identity of the killers and claimed that they would “take them out when the time was right”.[17] When Bratty and Elder were shot dead by the IRA in July 1994, revellers in the Lower Ormeau hailed the attack as revenge for Sean Graham’s.[18]

On 5 February 2002 a plaque was erected on the side of the bookmaker’s shop in Hatfield Street carrying the names of the five victims and the Irish language inscription Go ndéana Dia trócaire ar a n-anamacha (“May God have mercy on their souls”). A small memorial garden was later added.[19] The unveiling ceremony, which took place on the tenth anniversary of the attack, was accompanied by a two-minute silence and was attended by relatives of the dead and survivors of the attack.[20] A new memorial stone was laid on 5 February 2012 to coincide with the publication of a booklet calling for justice for the killings.[21]

Historical Enquiries Team findings

The attack was one of a number to be investigated by the Historical Enquiries Team (HET) in 2010. It found that a Browning pistol used by the gunmen had been given to them by the police. UDA quartermaster and police agent William Stobie had handed the gun to police and the police had given it back to him. Police “may have thought they had tampered with it to prevent it from being used”. According to the HET report this operation “would have required both the authority of a senior police officer and a recovery plan, generally short-term and where possible supported by the security forces within a short period of time. Clearly in this case, there was a significant failure and the repercussions were tragic and devastating”. The gun was, the report continued, also used in other UDA killings.[22]

Alex Maskey, a Sinn Féin MLA for the area, commented that “the finding by the HET that the Browning pistol used by the UDA in this attack was handed back to them by the RUC will come as no surprise to the people of the Lower Ormeau area who have long known that a high degree of collusion took place in this attack”.[22]

Officers from the HET were told by police that the assault rifle used in the attack had been “disposed of”. However, it was later discovered on display in the Imperial War Museum.[23]

Jackie McDonald

.jpg/220px-Jackie_McDonald_2014_(cropped).jpg)

In February 2012 Jackie McDonald, the incumbent commander of the UDA South Belfast Brigade (the area in which the shop is located), admitted that the victims of the shooting had been innocent. However, McDonald said that he could not apologise for the attack, arguing that as he was imprisoned at the time he played no part in what had happened.[11] In an earlier interview with Peter Taylor, McDonald suggested that it was the rise in sectarian killings and attacks such as that at Sean Graham’s that “brought about the ceasefire at the end of the day”.[9]

Attack on James Murray’s bookmakers

On the afternoon of 14 November 1992, the UDA carried out another attack on a betting shop in Belfast. The target was James Murray’s betting shop on the Oldpark Road in the north of the city, which was used mostly by Catholics.[24] One gunman fired into the shop from the doorway with an automatic weapon, while another smashed the window and threw a grenade inside. As he did so, he shouted “Yous deserve it, yous Fenian bastards!”.[25] Two Catholic civilians were killed outright and another died in hospital shortly after;[25] all of them were elderly men.[26] Thirteen others were wounded, some seriously. Like the shooting at Sean Graham’s, the November attack had also been planned by Adair. It “was followed by a raucous celebration in a loyalist club in south Belfast with Adair occupying centre stage”.[25] According to McDonald and Cusack the attack on this shop, which also had a few Protestant patrons who were present during the shooting, was carried out by Stephen McKeag.[27]

M62 Coach Bombing – 12 People including two children slaughtered by the IRA

The M62 coach bombing happened on 4 February 1974 on the M62 motorway in northern England, when a Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) bomb exploded in a coach carrying off-duty British Armed Forces personnel and their family members.

Twelve people (nine soldiers, three civilians) were killed by the bomb, which consisted of 25 pounds (11 kg) of high explosive hidden in a luggage locker on the coach. Judith Ward was convicted of the crime later in 1974, but 18 years later the conviction was judged as wrongful and she was released from prison.

The Bombing

The coach had been specially commissioned to carry British Army and Royal Air Force personnel on leave with their families from and to the bases at Catterick and Darlington during a period of railway strike action. The vehicle had departed from Manchester and was making good progress along the motorway. Shortly after midnight, when the bus was between junction 26 and 27, near Oakwell Hall, there was a large explosion on board. Most of those aboard were sleeping at the time. The blast, which could be heard several miles away, reduced the coach to a “tangle of twisted metal” and threw body parts up to 250 yards (230 m).

The explosion killed eleven people outright and wounded over fifty others , one of whom died four days later. Amongst the dead were nine soldiers – two from the Royal Artillery, three from the Royal Corps of Signals and four from the 2nd battalion Royal Regiment of Fusiliers.

One of the latter was Corporal Clifford Haughton, whose entire family, consisting of his wife Linda and his sons Lee (5) and Robert (2), also died. Numerous others suffered severe injuries, including a six-year-old boy, who was badly burned.

The driver of the coach, Roland Handley, was injured by flying glass, but was hailed as a hero for bringing the coach safely to a halt. Handley died, aged 76, after a short illness, in January 2011.

Suspicions immediately fell upon the IRA, which was in the midst of an armed campaign in Britain involving numerous operations, later including the Guildford Pub Bomb and the Birmingham pub bombings.

Reaction

Memorial plaque at Hartshead Moor services

Reactions in Britain were furious, with senior politicians from all parties calling for immediate action against the perpetrators and the IRA in general. The British media were equally condemnatory; according to The Guardian, it was:

“the worst IRA outrage on the British mainland” at that time, whilst the BBC has described it as “one of the IRA’s worst mainland terror attacks”.

The Irish Sunday Business Post later described it as the “worst” of the “awful atrocities perpetrated by the IRA” during this period.

IRA Army Council member Dáithí Ó Conaill was challenged over the bombing and the death of civilians during an interview, and replied that the coach was bombed because IRA intelligence indicated that it was carrying military personnel only.

The attack’s most lasting consequence was the adoption of much stricter ‘anti-terrorism‘ laws in Great Britain and Northern Ireland, allowing police to hold those ‘suspected of terrorism’ for up to seven days without charge, and to deport those ‘suspected of terrorism’ in Britain or the Republic of Ireland to Northern Ireland to face trial, where special courts judged with separate rules on ‘terrorism‘ suspects.

The entrance hall of the westbound section of the Hartshead Moor service area was used as a first aid station for those wounded in the blast. A memorial to those who were killed was later created there. following a campaign by relatives of the dead, a larger memorial was later erected, set some yards away from the entrance hall.

The site, situated behind four flag poles, includes an English oak tree, a memorial stone, a memorial plaque and a raised marble tablet inscribed with the names of those who died.

A memorial plaque engraved with the names of the casualties was also unveiled in Oldham in 2010.

M62 coach bombing

—————————————————————————

Victims

—————————————————————————

04 February 1974

Leonard Godden, (22)

nfNIB

Status: British Army (BA),

Killed by: Irish Republican Army (IRA)

Killed in time bomb attack on British Army (BA) coach travelling along M62 motorway, Yorkshire, England.

—————————————————————————

04 February 1974

Terence Griffin, (24)

nfNIB

Status: British Army (BA),

Killed by: Irish Republican Army (IRA)

Killed in time bomb attack on British Army (BA) coach travelling along M62 motorway, Yorkshire, England.

—————————————————————————

04 February 1974

Michael Waugh, (22)

nfNIB

Status: British Army (BA),

Killed by: Irish Republican Army (IRA)

Killed in time bomb attack on British Army (BA) coach travelling along M62 motorway, Yorkshire, England.

—————————————————————————

04 February 1974

Leslie Walsh, (19)

nfNI

Status: British Army (BA),

Killed by: Irish Republican Army (IRA)

Killed in time bomb attack on British Army (BA) coach travelling along M62 motorway, Yorkshire, England.

—————————————————————————

04 February 1974

Paul Reid, (17)

nfNIB

Status: British Army (BA),

Killed by: Irish Republican Army (IRA)

Killed in time bomb attack on British Army (BA) coach travelling along M62 motorway, Yorkshire, England

—————————————————————————

04 February 1974

Jack Hynes, (19)

nfNIB

Status: British Army (BA),

Killed by: Irish Republican Army (IRA)

Killed in time bomb attack on British Army (BA) coach travelling along M62 motorway, Yorkshire, England.

—————————————————————————

04 February 1974

James McShane, (28)

nfNIB

Status: British Army (BA),

Killed by: Irish Republican Army (IRA)

Killed in time bomb attack on British Army (BA) coach travelling along M62 motorway, Yorkshire, England.

—————————————————————————

04 February 1974

Clifford Houghton, (23)

nfNIB

Status: British Army (BA),

Killed by: Irish Republican Army (IRA)

Killed in time bomb attack on British Army (BA) coach travelling along M62 motorway, Yorkshire, England

—————————————————————————

04 February 1974

Linda Houghton, (23)

nfNIB

Status: Civilian (Civ),

Killed by: Irish Republican Army (IRA)

Killed in time bomb attack on British Army (BA) coach travelling along M62 motorway, Yorkshire, England

—————————————————————————

04 February 1974

Lee Houghton, (5)

nfNIB

Status: Civilian (Civ),

Killed by: Irish Republican Army (IRA)

Killed in time bomb attack on British Army (BA) coach travelling along M62 motorway, Yorkshire, England

—————————————————————————

04 February 1974

Robert Houghton, (2)

nfNIB

Status: Civilian (Civ),

Killed by: Irish Republican Army (IRA)

Killed in time bomb attack on British Army (BA) coach travelling along M62 motorway, Yorkshire, England.

—————————————————————————

04 February 1974

Stephen Whalley, (18)

nfNIB

Status: British Army (BA),

Killed by: Irish Republican Army (IRA)

Injured in time bomb attack on British Army (BA) coach travelling along M62 motorway, Yorkshire, England. He died 7 February 1974.

—————————————————————————

See: Palace Barracks Memorial Garden

04 February 1974

Prosecution

Following the explosion, the British public and politicians from all three major parties called for “swift justice”. The ensuing police investigation led by Detective Chief Superintendent George Oldfield was rushed, careless and ultimately forged, resulting in the arrest of the mentally ill Judith Ward who claimed to have conducted a string of bombings in Britain in 1973 and 1974 and to have married and had a baby with two separate IRA members. Despite her retraction of these claims, the lack of any corroborating evidence against her, and serious gaps in her testimony – which was frequently rambling, incoherent and “improbable” – she was wrongfully convicted in November 1974. Following her conviction, the Irish Republican Publicity Bureau issued a statement:

Miss Ward was not a member of Óglaigh na hÉireann and was not used in any capacity by the organisation. She had nothing to do what-so-ever with the military coach bomb (on 4 February 1974), the bombing of Euston Station and the attack on Latimer Military College. Those acts were authorised operations carried out by units of the Irish Republican Army.

The case against her was almost completely based on inaccurate scientific evidence using the Griess test and deliberate manipulation of her confession by some members of the investigating team. The case was similar to those of the Guildford Four, the Birmingham Six and the Maguire Seven, which occurred at the same time and involved similar forged confessions and inaccurate scientific analysis. Ward was finally released in 1992, when three Appeal Court judges held unanimously that her conviction was “a grave miscarriage of justice”, and that it had been “secured by ambush

See: Guildford Pub Bomb

Segregation in Northern Ireland

Segregation in Northern Ireland

Segregation in Northern Ireland is a long-running issue in the political and social history of Northern Ireland. The segregation involves Northern Ireland’s two main voting blocs – Irish nationalist/republicans (mainly Roman Catholic) and unionist/loyalist (mainly Protestant). It is often seen as both a cause and effect of the “Troubles“.

A combination of political, religious and social differences plus the threat of intercommunal tensions and violence has led to widespread self-segregation of the two communities. Catholics and Protestants lead largely separate lives in a situation that some have dubbed “self-imposed apartheid”.[1] The academic John H. Whyte argued that “the two factors which do most to divide Protestants as a whole from Catholics as a whole are endogamy and separate education

———————————————————

Inside Story – How divided is Northern Ireland

———————————————————

Education

Education in Northern Ireland is heavily segregated. Most state schools in Northern Ireland are predominantly Protestant, while the majority of Catholic children attend schools maintained by the Catholic Church. In all, 90 per cent of children in Northern Ireland still go to separate faith schools.[3] The consequence is, as one commentator has put it, that “the overwhelming majority of Ulster’s children can go from four to 18 without having a serious conversation with a member of a rival creed.”[4] The prevalence of segregated education has been cited as a major factor in maintaining endogamy (marriage within one’s own group).[5] The integrated education movement has sought to reverse this trend by establishing non-denominational schools such as the Portadown Integrated Primary. Such schools are, however, still the exception to the general trend of segregated education. Integrated schools in Northern Ireland have been established through the voluntary efforts of parents. The churches have not been involved in the development of integrated education.[6]

———————————————————

Why Ireland split into the Republic of Ireland & Northern Ireland

———————————————————

Employment

Historically, employment in the Northern Irish economy was highly segregated in favour of Protestants, particularly at senior levels of the public sector, in certain then important sectors of the economy, such as shipbuilding and heavy engineering, and strategically important areas such as the police.[7] Emigration to seek employment was therefore significantly more prevalent among the Catholic population. As a result, Northern Ireland’s demography shifted further in favour of Protestants leaving their ascendancy seemingly impregnable by the late 1950s.

A 1987 survey found that 80 per cent of the workforces surveyed were described by respondents as consisting of a majority of one denomination; 20 per cent were overwhelmingly unidenominational, with 95–100 per cent Catholic or Protestant employees. However, large organisations were much less likely to be segregated, and the level of segregation has decreased over the years.[8]

The British government has introduced numerous laws and regulations since the mid-1990s to prohibit discrimination on religious grounds, with the Fair Employment Commission (originally the Fair Employment Agency) exercising statutory powers to investigate allegations of discriminatory practices in Northern Ireland business and organisations.[7] This has had a significant impact on the level of segregation in the workplace;[8] John Whyte concludes that the result is that “segregation at work is one of the least acute forms of segregation in Northern Ireland.” [9]

———————————————————

BBC Spotlight – Poverty in Northern Ireland

———————————————————

Housing

Gates in a peace line in West Belfast

Public housing is overwhelmingly segregated between the two communities. Intercommunal tensions have forced substantial numbers of people to move from mixed areas into areas inhabited exclusively by one denomination, thus increasing the degree of polarisation and segregation. The extent of self-segregation grew very rapidly with the outbreak of the Troubles. In 1969, 69 per cent of Protestants and 56 per cent of Catholics lived in streets where they were in their own majority; as the result of large-scale flight from mixed areas between 1969 and 1971 following outbreaks of violence, the respective proportions had by 1972 increased to 99 per cent of Protestants and 75 per cent of Catholics.[10] In Belfast, the 1970s were a time of rising residential segregation.[11] It was estimated in 2004 that 92.5% of public housing in Northern Ireland was divided along religious lines, with the figure rising to 98% in Belfast.[1] Self-segregation is a continuing process, despite the Northern Ireland peace process. It was estimated in 2005 that more than 1,400 people a year were being forced to move as a consequence of intimidation.[12]

In response to intercommunal violence, the British Army constructed a number of high walls called “peace lines” to separate rival neighbourhoods. These have multiplied over the years and now number forty separate barriers, mostly located in Belfast. Despite the moves towards peace between Northern Ireland’s political parties and most of its paramilitary groups, the construction of “peace lines” has actually increased during the ongoing peace process; the number of “peace lines” doubled in the ten years between 1995 and 2005.[13] In 2008 a process was proposed for the removal of the peace walls.[14]

The effective segregation of the two communities significantly affects the usage of local services in “interface areas” where sectarian neighbourhoods adjoin. Surveys in 2005 of 9,000 residents of interface areas found that 75% refused to use the closest facilities because of location, while 82% routinely travelled to “safer” areas to access facilities even if the journey time was longer. 60% refused to shop in areas dominated by the other community, with many fearing ostracism by their own community if they violated an unofficial de facto boycott of their sectarian opposite numbers.[13]

Intermarriage

In contrast with both the Republic of Ireland and most parts of Great Britain, where intermarriage between Protestants and Catholics is not unusual, in Northern Ireland it has been uncommon: from 1970 through to the 1990s, only 5 per cent of marriages were recorded as crossing community divides.[15] This figure remained largely constant throughout the Troubles. It rose to between 8 and 12 per cent, according to the Northern Ireland Life and Times Survey, in 2003, 2004 and 2005.[16][17][18] Attitudes towards Catholic–Protestant intermarriage have become more supportive in recent years (particularly among the middle class)[19] and younger people are also more likely to be married to someone of a different religion to themselves than older people. However, the data hides considerable regional variation across Northern Ireland.[20]

Anti-discrimination legislation

In the 1970s, the British government took action to legislate against religious discrimination in Northern Ireland. The Fair Employment Act 1976 prohibited discrimination in the workplace on the grounds of religion and established a Fair Employment Agency. This Act was strengthened with a new Fair Employment Act in 1989, which introduced a duty on employers to monitor the religious composition of their workforce, and created the Fair Employment Commission to replace the Fair Employment Agency. The law was extended to cover the provision of goods, facilities and services in 1998 under the Fair Employment and Treatment (Northern Ireland) Order 1998.[21] In 1999, the Commission was merged with the Equal Opportunities Commission, the Commission for Racial Equality and the Northern Ireland Disability Council to become part of the Equality Commission for Northern Ireland.[22]

An Equality Commission review in 2004 of the operation of the anti-discrimination legislation since the 1970s, found that there had been a substantial improvement in the employment profile of Catholics, most marked in the public sector but not confined to it. It said that Catholics were now well represented in managerial, professional and senior administrative posts, although there were some areas of under-representation such as local government and security but that the overall picture was a positive one. Catholics, however, were still more likely than Protestants to be unemployed and there were emerging areas of Protestant under-representation in the public sector, most notably in health and education at many levels including professional and managerial. The report also found that there had been a considerable increase in the numbers of people who work in integrated workplaces.

30th January – Deaths & Events in Northern Ireland Troubles

Key Events & Deaths on this day in Northern Ireland Troubles

30th January

——————————–

Sunday 30 January 1972

‘Bloody Sunday’ ‘Bloody Sunday‘ refers to the shooting dead by the British Army of 13 civilans (and the wounding of another 14 people, one of whom later died) during a Civil Rights march in Derry. The Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (NICRA) march against internment was meant to start at 2.00pm from the Creggan. The march left late (2.50pm approximately) from Central Drive in the Creggan Estate and took an indirect route towards the Bogside area of the city. People joined the march along its entire route.

At approximately 3.25pm the march passed the ‘Bogside Inn’ and turned up Westland Street before going down William Street. Estimates of the number of marchers at this point vary. Some observers put the number as high as 20,000 whereas the Widgery Report estimated the number at between 3,000 and 5,000. Around 3.45pm most of the marchers followed the organisers instructions and turned right into Rossville Street to hold a meeting at ‘Free Derry Corner’. However a section of the crowd continued along William Street to the British Army barricade. A riot developed. (Confrontations between the Catholic youth of Derry and the British Army had become a common feature of life in the city and many observers reported that the rioting was not particularly intense.)

At approximately 3.55pm, away from the riot and also out of sight of the meeting, soldiers (believed to be a machine-gun platoon of Paratroopers) in a derelict building in William Street opened fire (shooting 5 rounds) and injured Damien Donaghy (15) and John Johnston (59). Both were treated for injuries and were taken to hospital (Johnston died on 16 June 1972).

[The most recent information (see, for example, Pringle, P. and Jacobson, P.; 2000) suggests that an Official IRA member then fired a single shot in response at the soldiers in the derelict building. This incident happened prior to the main shooting and also out of sight of Rossville Street.]

Also around this time (about 3.55pm) as the riot in William Street was breaking up, Paratroopers requested permission to begin an arrest operation. By about 4.05pm most people had moved to ‘Free Derry Corner’ to attend the meeting. 4.07pm (approximately) An order was given for a ‘sub unit’ (Support Company) of the 1st Battalion Parachute Regiment to move into William Street to begin an arrest operation directed at any remaining rioters. The order authorising the arrest operation specifically stated that the soldiers were “not to conduct running battle down Rossville Street”

(Official Brigade Log). The soldiers of Support Company were under the command of Ted Loden, then a Major in the Parachute Regiment (and were the only soldiers to fire at the crowd from street level).

At approximately 4.10pm soldiers of the Support Company of the 1st Battalion Parachute Regiment began to open fire on people in the area of Rossville Street Flats. By about 4.40pm the shooting ended with 13 people dead and a further 14 injured from gunshots. The shooting took place in four main places: the car park (courtyard) of Rossville Flats; the forecourt of Rossville Flats (between the Flats and Joseph Place); at the rubble and wire barricade on Rossville Street (between Rossville Flats and Glenfada Park); and in the area around Glenfada Park (between Glenfada Park and Abbey Park).

According to British Army evidence 21 soldiers fired their weapons on ‘Bloody Sunday’ and shot 108 rounds in total.

[Most of the basic facts are agreed, however what remains in dispute is whether or not the soldiers came under fire as they entered the area of Rossville Flats. The soldiers claimed to have come under sustained attack by gunfire and nail-bomb. None of the eyewitness accounts saw any gun or bomb being used by those who had been shot dead or wounded. No soldiers were injured in the operation, no guns or bombs were recovered at the scene of the killing.]

[Public Records 1972 – Released 1 January 2003: Telegram from Lord Bridges to Edward Heath, then British Prime Minister, containing an early report of the killings in Derry.]

Tuesday 30 January 1973

Francis Smith (28), a member of the Ulster Defence Association (UDA), was found shot dead in the Falls area of Belfast. He had been killed by the IRA.

Wednesday 30 January 1974

[ Sunningdale; Ulster Workers’ Council Strike; Law Order. ]

Wednesday 30 January 1975

The Gardiner Report (Cmnd. 5847), which examined measures to deal with terrorism within the context of human rights and civil liberties, was published. The report recommended that special category status for paramilitary prisoners should be ended. The report also recommended that detention without trial be maintained but under the control of the Secretary of State.

30 January 1983

At the annual conference of the Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP) the delegates reaffirmed the party’s boycott of the Northern Ireland Assembly.

Monday 30 January 1984

The Prison Governors’ Association and the Prison Officers Association both claimed that political interference in the running of the Maze Prison resulted in the mass escape on 25 September 1983. Nick Scott, then Minister for Prisons, rejected the allegations.

[See also: 25 October 1984]

Wednesday 30 January 1985

Douglas Hurd, then Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, dismissed demands for the disbandment of the Ulster Defence Regiment (UDR).

Thursday 30 January 1986

Fianna Fáil (FF) said that it welcomed the comments of Harold McCusker, then deputy leader of the Ulster Unionist Party (UUP), who had suggested a conference of British, Irish, and Northern Ireland politicians to discuss the ‘totality of relationships’.

Thursday 30 January 1992

Charles Haughey, then Taoiseach (Irish Prime Minister), announced his resignation as both Taoiseach and leader of Fianna Fáil (FF). [Haughey’s resignation followed the re-emergence of allegations about phone-tapping in 1982.]

Saturday 30 January 1993

There was a rally in Derry to commemorate the 21st anniversary of the killings on ‘Bloody Sunday’ (30 January 1972).

Monday 30 January 1995

Bertie Ahern, then leader of Fianna Fáil (FF), held a meeting with the Ulster Unionist Party (UUP) at its headquarters in Glengall Street, Belfast. Ahern also met with Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP) and Sinn Féin (SF) members later in the day.

Tuesday 30 January 1996

Gino Gallagher (33), believed to be the Chief of Staff of the Irish National Liberation Army (INLA), was shot dead in a Social Security Office in the Falls Road, Belfast.

[This killing was to mark the beginning of another feud within the INLA. This particular feud ended on 3 September 1996.]

Gerry Adams, then President of Sinn Féin (SF), held a meeting with Patrick Mayhew, then Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, at Stormont. John Hume, then leader of the Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP), met with John Major, then British Prime Minister, in Downing Street, London.

Thursday 30 January 1997

North Report Peter North, then Chairman of the Independent Review of Parades and Marches, launched his report (The North Report) in Belfast and recommended the setting up of an independent commission to review contentious parades. Most Nationalists welcomed the Review but Unionists were against the main recommendations. Patrick Mayhew, then Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, announced that “further consultation” would have to be carried out by the Northern Ireland Office (NIO) before any decisions could be taken. Marjorie (Mo) Mowlam, then Labour Party Spokesperson on Northern Ireland, approved of the report.

Saturday 30 January 1999

Loyalist paramilitaries carried out seven ‘punishment’ beatings against people in Newtownabbey, County Antrim. Republican paramilitaries carried out a ‘punishment’ shooting on a man in Cookstown, County Tyrone. [January had the highest level of paramilitary ‘punishment’ attacks during any month in the past 10 years.]

Wednesday 30 January 2002

Relatives of those killed on Bloody Sunday (30 January 1972), together with some of the surviving injured, and about 2,000 other people, gathered in the Bogside in Derry to mark the 30th anniversary of the killings. A minute’s silence was held at the time when the first shots were fired. Dr Edward Daly, the former Bishop of Derry, rededicated the memorial to the dead. In his address he said he prayed “for victims everywhere – here, in Afghanistan, the Middle East and New York”. He added:

“We identify with all people who have suffered, of whatever race or religion or nation”. The Bloody Sunday Inquiry was adjourned until Monday – the Inquiry does not sit on the anniversary of the killings.

[The Inquiry will resume on Monday when the first Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) witnesses are expected to begin giving evidence. It is anticipated that one of the police witnesses will give evidence from behind a screen.]

David Ford, then leader of the Alliance Party of Northern Ireland (APNI), travelled to Downing Street, London, for a meeting with Tony Blair, then British Prime Minister. Ford was there to discuss potential reforms of the voting system used in the Northern Ireland Assembly. David Trimble (UUP), then First Minister, and Mark Durkan (SDLP), then Deputy First Minister, travelled to Brussels for a two day visit. During their first day they opened a new Northern Ireland Executive office in the city which was established to lobby on behalf of Northern Ireland within the European Parliament.

The cost of the office, which was higher than envisaged, came in for criticism. The set up cost was £300,000 and the annual running cost is estimated at £500,000. The Irish National Liberation Army denied that it had threatened Protestant community workers in Glenbryn, north Belfast. The denial was issued through the Irish Republican Socialist Party (IRSP). It described the threats as bogus.

—————————————————————————

Remembering all innocent victims of the Troubles

Today is the anniversary of the death of the following people killed as a results of the conflict in Northern Ireland

“To live in hearts we leave behind is not to die

– Thomas Campbell

To the innocent on the list – Your memory will live forever

– To the Paramilitaries –

There are many things worth living for, a few things worth dying for, but nothing worth killing for.

22 People lost their lives on the 30th January between 1972 – 1996

—————————————————————————

30 January 1972

Robin Alers-Hankey, (35)

nfNI

Status: British Army (BA),

Killed by: Irish Republican Army (IRA)

Died four months after being shot by sniper during street disturbances, Abbey Street, Bogside, Derry. He was wounded on 2 September 1971.

—————————————————————————

30 January 1972

John Duddy, (17)

Catholic

Status: Civilian (Civ),

Killed by: British Army (BA)

Shot during anti-internment march in the vicinity of Rossville Street, Bogside, Derry.

—————————————————————————

30 January 1972

Kevin McElhinney, (17)

Catholic

Status: Civilian (Civ),

Killed by: British Army (BA)

Shot during anti-internment march in the vicinity of Rossville Street, Bogside, Derry

—————————————————————————

30 January 1972

Patrick Doherty, (31)

Catholic

Status: Civilian (Civ),

Killed by: British Army (BA)

Shot during anti-internment march in the vicinity of Rossville Street, Bogside, Derry

—————————————————————————

30 January 1972

Bernard McGuigan, (41)

Catholic

Status: Civilian (Civ),

Killed by: British Army (BA)

Shot during anti-internment march in the vicinity of Rossville Street, Bogside, Derry

—————————————————————————

30 January 1972

Hugh Gilmour, (17)

Catholic

Status: Civilian (Civ),

Killed by: British Army (BA)

Shot during anti-internment march in the vicinity of Rossville Street, Bogside, Derry

—————————————————————————

30 January 1972

William Nash, (19)

Catholic

Status: Civilian (Civ),

Killed by: British Army (BA)

Shot during anti-internment march in the vicinity of Rossville Street, Bogside, Derry.

—————————————————————————

30 January 1972

Michael McDaid, (20)

Catholic

Status: Civilian (Civ),

Killed by: British Army (BA)

Shot during anti-internment march in the vicinity of Rossville Street, Bogside, Derry

—————————————————————————

30 January 1972

John Young, (17)

Catholic

Status: Civilian (Civ),

Killed by: British Army (BA)

Shot during anti-internment march in the vicinity of Rossville Street, Bogside, Derry

—————————————————————————

30 January 1972

Michael Kelly, (17)

Catholic

Status: Civilian (Civ),

Killed by: British Army (BA)

Shot during anti-internment march in the vicinity of Rossville Street, Bogside, Derry

—————————————————————————

30 January 1972

James Wray, (22)

Catholic

Status: Civilian (Civ),

Killed by: British Army (BA)

Shot during anti-internment march in the vicinity of Rossville Street, Bogside, Derry

—————————————————————————

30 January 1972

Gerry Donaghy, (17)

Catholic

Status: Irish Republican Army Youth Section (IRAF),

Killed by: British Army (BA)

Shot during anti-internment march in the vicinity of Rossville Street, Bogside, Derry

—————————————————————————

30 January 1972

Gerald McKinney, (35)

Catholic

Status: Civilian (Civ),

Killed by: British Army (BA)

Shot during anti-internment march in the vicinity of Rossville Street, Bogside, Derry

—————————————————————————

30 January 1972

William McKinney, (26)

Catholic

Status: Civilian (Civ),

Killed by: British Army (BA)

Shot during anti-internment march in the vicinity of Rossville Street, Bogside, Derry

—————————————————————————

30 January 1972

John Johnston, (59)

Catholic

Status: Civilian (Civ),

Killed by: British Army (BA)

Shot during anti-internment march in the vicinity of Rossville Street, Bogside, Derry. He died 16 June 1972.

—————————————————————————

30 January 1973

Francis Smith, (28)

Protestant

Status: Ulster Defence Association (UDA),

Killed by: Irish Republican Army (IRA)

Found shot in entry, off Rodney Parade, Falls, Belfast.

—————————————————————————

30 January 1974

Thomas Walker, (36)

Protestant

Status: Civilian (Civ),

Killed by: non-specific Loyalist group (LOY)

Shot at his home, Gosford Place, off McClure Street, Belfast. Alleged informer.

—————————————————————————

30 January 1976

John Smiley, (55)

Protestant

Status: Civilian (Civ),

Killed by: Irish Republican Army (IRA)

Killed in bomb attack on Klondyke Bar, Sandy Row, Belfast.

—————————————————————————

30 January 1976

Samuel Hollywood, (34)

Protestant

Status: Ulster Defence Association (UDA),

Killed by: Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF)

Stabbed to death, outside North Star Bar, North Queen Street, Tiger’s Bay, Belfast. Ulster Defence Association (UDA) / Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) feud.

—————————————————————————

30 January 1984

Mark Marron, (23)

Catholic

Status: Civilian (Civ),

Killed by: British Army (BA)

Shot while travelling in stolen car, Springfield Road, Belfast.

—————————————————————————

30 January 1992

Paul Moran, (32)

Catholic

Status: Civilian (Civ),

Killed by: Ulster Freedom Fighters (UFF)

Shot outside newsagent’s shop, while on way to work, Longstone Street, Lisburn, County Antrim.

—————————————————————————

30 January 1996

Gino Gallagher, (33)

Catholic

Status: Irish National Liberation Army (INLA),

Killed by: Irish National Liberation Army (INLA)

Shot, while inside Department of Health and Social Services office, Falls Road, Belfast. Internal Irish National Liberation Army dispute.

—————————————————————————

Bloody Sunday – 30 January 1972

Bloody Sunday

See Bloody Friday

Bloody Sunday – sometimes called the Bogside Massacre[1] – was an incident on 30 January 1972 in the Bogside area of Derry, Northern Ireland. British soldiers shot 26 unarmed civilians during a protest march against internment. Fourteen people died: thirteen were killed outright, while the death of another man four-and-a-half months later was attributed to his injuries. Many of the victims were shot while fleeing from the soldiers and some were shot while trying to help the wounded. Two protesters were also injured when they were run down by army vehicles.[2][3] The march had been organised by the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association and the Northern Resistance Movement.[4] The soldiers involved were members of the 1st Battalion, Parachute Regiment, also known as “1 Para”.

My Thoughts?

The death of all innocent people during the Troubles has always had a profound effect on me and Bloody Sunday was one of the darkest days (of many) in Northern Irelands tortured past.

However I don’t think Republicans have been completely honest regarding their involvements in the events of that day and they should shoulder some of the blame.

I don’t wish to take anything away from the innocent victims by any means, I’m just saying that things happened that day that put in motion a chain of events that lead to many innocent people dying and all those responsible should be honest and open about exactly what happened. But as we all know SF/IRA rewrite the history of the Troubles on a daily basis and seem to accept NO responsibility for the indiscriminate slaughter of innocent people that hunted the streets of Belfast, N.I and mainland UK.for thirty long , brutal years.

Thank God those days are now behind us.

— Disclaimer –

The views and opinions expressed in this post/documentaries are soley intended to educate and provide background information to those interested in the Troubles of Northern Ireland. They in no way reflect my own opinions and I take no responsibility for any inaccuracies or factual errors.

———————————-

Bloody Sunday – 30th January 1972

———————————-

Two investigations have been held by the British government. The Widgery Tribunal, held in the immediate aftermath of the incident, largely cleared the soldiers and British authorities of blame. It described the soldiers’ shooting as “bordering on the reckless”, but accepted their claims that they shot at gunmen and bomb-throwers. The report was widely criticised as a “whitewash“.[6][7][8] The Saville Inquiry, chaired by Lord Saville of Newdigate, was established in 1998 to reinvestigate the incident. Following a 12-year inquiry, Saville’s report was made public in 2010 and concluded that the killings were both “unjustified” and “unjustifiable”. It found that all of those shot were unarmed, that none were posing a serious threat, that no bombs were thrown, and that soldiers “knowingly put forward false accounts” to justify their firing.[9][10] On the publication of the report, British prime minister David Cameron made a formal apology on behalf of the United Kingdom.[11] Following this, police began a murder investigation into the killings.

Bloody Sunday was one of the most significant events of “the Troubles” because a large number of civilians were killed, by state forces, in full view of the public and the press.[1] It was the highest number of people killed in a single shooting incident during the conflict.[12] Bloody Sunday increased Catholic and Irish nationalist hostility towards the British Army and exacerbated the conflict. Support for the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) rose and there was a surge of recruitment into the organisation, especially locally

———————————-

Bloody Sunday Part

———————————-

Background

Main article: The Troubles

The City of Derry was perceived by many Catholics and Irish nationalists in Northern Ireland to be the epitome of what was described as “fifty years of Unionist misrule”: despite having a nationalist majority, gerrymandering ensured elections to the City Corporation always returned a unionist majority. At the same time the city was perceived to be deprived of public investment – rail routes to the city were closed, motorways were not extended to it, a university was opened in the relatively small (Protestant-majority) town of Coleraine rather than Derry and, above all, the city’s housing stock was in an appalling state.[14] The city therefore became a significant focus of the civil rights campaign led by organisations such as Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (NICRA) in the late 1960s and it was in Derry that the so-called Battle of the Bogside – the event that more than any other pushed the Northern Ireland administration to ask for military support for civil policing – took place in August 1969.[15]

While many Catholics initially welcomed the British Army as a neutral force, in contrast to what was regarded as a sectarian police force, relations between them soon deteriorated.[16]

In response to escalating levels of violence across Northern Ireland, internment without trial was introduced on 9 August 1971.[17] There was disorder across Northern Ireland following the introduction of internment, with 21 people being killed in three days of rioting.[18] In Belfast, soldiers of the Parachute Regiment shot dead 11 Catholic civilians in what became known as the Ballymurphy Massacre. On 10 August, Bombardier Paul Challenor became the first soldier to be killed by the Provisional IRA in Derry, when he was shot by a sniper on the Creggan estate.[19] A further six soldiers had been killed in Derry by mid-December 1971.[20] At least 1,332 rounds were fired at the British Army, who also faced 211 explosions and 180 nail bombs,[20] and who fired 364 rounds in return.

IRA activity also increased across Northern Ireland with thirty British soldiers being killed in the remaining months of 1971, in contrast to the ten soldiers killed during the pre-internment period of the year.[18] Both the Official IRA and Provisional IRA had established no-go areas for the British Army and RUC in Derry through the use of barricades.[21] By the end of 1971, 29 barricades were in place to prevent access to what was known as Free Derry, 16 of them impassable even to the British Army’s one-ton armoured vehicles.[21] IRA members openly mounted roadblocks in front of the media, and daily clashes took place between nationalist youths and the British Army at a spot known as “aggro corner”.[21] Due to rioting and damage to shops caused by incendiary devices, an estimated total of £4 million worth of damage had been done to local businesses.[21]

On 18 January 1972 Brian Faulkner, Prime Minister of Northern Ireland, banned all parades and marches in Northern Ireland until the end of the year.

On 22 January 1972, a week before Bloody Sunday, an anti-internment march was held at Magilligan strand, near Derry. The protesters marched to a new internment camp there, but were stopped by soldiers of the Parachute Regiment. When some protesters threw stones and tried to go around the barbed wire, Paratroopers drove them back by firing rubber bullets at close range and making baton charges. The Paratroopers badly beat a number of protesters and had to be physically restrained by their own officers. These allegations of brutality by Paratroopers were reported widely on television and in the press. Some in the Army also thought there had been undue violence by the Paratroopers.[22][23]

NICRA intended, despite the ban, to hold another anti-internment march in Derry on Sunday 30 January. The authorities decided to allow it to proceed in the Catholic areas of the city, but to stop it from reaching Guildhall Square, as planned by the organisers. The authorities expected that this would lead to rioting. Major General Robert Ford, then Commander of Land Forces in Northern Ireland, ordered that the 1st Battalion, Parachute Regiment (1 Para), should travel to Derry to be used to arrest possible rioters.[24] The arrest operation was codenamed ‘Operation Forecast’.[25] The Saville Report criticised General Ford for choosing the Parachute Regiment for the operation, as it had “a reputation for using excessive physical violence”.[26] The paratroopers arrived in Derry on the morning of the march and took up positions in the city.[27] Brigadier Pat MacLellan was the operational commander and issued orders from Ebrington Barracks. He gave orders to Lieutenant Colonel Derek Wilford, commander of 1 Para. He in turn gave orders to Major Ted Loden, who commanded the company who launched the arrest operation.

Events of the day

Main article: Narrative of events of Bloody Sunday (1972)

The Bogside in 1981, overlooking the area where many of the victims were shot. On the right of the picture is the south side of Rossville Flats, and in the middle distance is Glenfada Park

The protesters planned on marching from Bishop’s Field, in the Creggan housing estate, to the Guildhall, in the city centre, where they would hold a rally. The march set off at about 2:45pm. There were 10–15,000 people on the march, with many joining along its route.[28] Lord Widgery, in his now discredited tribunal,[29][30][31][32] said that there were only 3,000 to 5,000.

The march made its way along William Street but, as it neared the city centre, its path was blocked by British Army barriers. The organisers redirected the march down Rossville Street, intending to hold the rally at Free Derry Corner instead. However, some broke off from the march and began throwing stones at soldiers manning the barriers. The soldiers fired rubber bullets, CS gas and water cannon to try and disperse the rioters.[33] Such clashes between soldiers and youths were common, and observers reported that the rioting was not intense.[34]

Some of the crowd spotted paratroopers hiding in a derelict three-storey building overlooking William Street, and began throwing stones at the windows. At about 3:55pm, these paratroopers opened fire. Civilians Damien Donaghy and John Johnston were shot and wounded while standing on waste ground opposite the building. These were the first shots fired.[35] The soldiers claimed Donaghy was holding a black cylindrical object.[36]

At 4:07pm, the paratroopers were ordered to go through the barriers and arrest rioters. The paratroopers, on foot and in armoured vehicles, chased people down Rossville Street and into the Bogside. Two people were knocked down by the vehicles. Brigadier MacLellan had ordered that only one company of paratroopers be sent through the barriers, on foot, and that they should not chase people down Rossville Street. Colonel Wilford disobeyed this order, which meant there was no separation between rioters and peaceful marchers.[37]

The paratroopers disembarked and began seizing people. There were many claims of paratroopers beating people, clubbing them with rifle butts, firing rubber bullets at them from close range, making threats to kill, and hurling abuse. The Saville Report agreed that soldiers “used excessive force when arresting people […] as well as seriously assaulting them for no good reason while in their custody”.[38]

One group of paratroopers took up position at a low wall about 80 yards (73 m) in front of a rubble barricade that stretched across Rossville Street. There were people at the barricade and some were throwing stones at the soldiers, but none were near enough to hit them.[39] The soldiers fired on the people at the barricade, killing six and wounding a seventh.[40]

A large group of people fled or were chased into the car park of Rossville Flats. This area was like a courtyard, surrounded on three sides by high-rise flats. The soldiers opened fire, killing one civilian and wounding six others.[41] This fatality, Jackie Duddy, was running alongside a priest, Father Edward Daly, when he was shot in the back.[42]

Another group of people fled into the car park of Glenfada Park, which was also a courtyard-like area surrounded by flats. Here, the soldiers shot at people across the car park, about 40–50 yards away. Two civilians were killed and at least four others wounded.[43] The Saville Report says it is “probable” that at least one soldier fired from the hip towards the crowd, without aiming.[44]

The soldiers went through the car park and out the other side. Some soldiers went out the southwest corner, where they shot dead two civilians. The other soldiers went out the southeast corner and shot four more civilians, killing two.[45]

About ten minutes had elapsed between the time soldiers drove into the Bogside and the time the last of the civilians was shot.[46] More than 100 rounds were fired by the soldiers, who were under the command of Major Ted Loden.

Some of those shot were given first aid by civilian volunteers, either on the scene or after being carried into nearby homes. They were then driven to hospital, either in civilian cars or in ambulances. The first ambulances arrived at 4:28pm. The three boys killed at the rubble barricade were driven to hospital by the paratroopers. Witnesses said paratroopers lifted the bodies by the hands and feet and dumped them in the back of their APC, as if they were “pieces of meat”. The Saville Report agreed that this is an “accurate description of what happened”. It says the paratroopers “might well have felt themselves at risk, but in our view this does not excuse them”.[47]

The dead

In all, 26 people were shot by the paratroopers; 13 died on the day and another died four months later. Most of them were killed in four main areas: the rubble barricade across Rossville Street, the courtyard car park of Rossville Flats (on the north side of the flats), the courtyard car park of Glenfada Park, and the forecourt of Rossville Flats (on the south side of the flats).[42]

All of the soldiers responsible insisted that they had shot at, and hit, gunmen or bomb-throwers. The Saville Report concluded that all of those shot were unarmed and that none were posing a serious threat. It also concluded that none of the soldiers fired in response to attacks, or threatened attacks, by gunmen or bomb-throwers.[49]

The casualties are listed in the order in which they were killed

John ‘Jackie’ Duddy,

age 17.

Shot as he ran away from soldiers in the car park of Rossville Flats.[42] The bullet struck him in the shoulder and entered his chest. Three witnesses said they saw a soldier take deliberate aim at the youth as he ran.[42] He was the first fatality on Bloody Sunday.[42] Like Saville, Widgery also concluded that Kelly was unarmed.[42] His nephew is boxer John Duddy.

Michael Kelly,

age 17