Battle of Rorke’s Drift

22–23 January 1879

Location

Rorke’s Drift, Natal Province, South Africa

Greatest Scenes in Movies, EVER

———————————————————————–

The Battle of Rorke’s Drift

The Battle of Rorke’s Drift, also known as the Defence of Rorke’s Drift, was a battle in the Anglo-Zulu War. The defence of the mission station of Rorke’s Drift, under the command of Lieutenant John Chard of the Royal Engineers, and Lieutenant Gonville Bromhead immediately followed the British Army‘s defeat at the Battle of Isandlwana on 22 January 1879, and continued into the following day, 23 January.

Just over 150 British and colonial troops successfully defended the garrison against an intense assault by 3,000 to 4,000 Zulu warriors. The massive, but piecemeal, Zulu attacks on Rorke’s Drift came very close to defeating the tiny garrison but were ultimately repelled. Eleven Victoria Crosses were awarded to the defenders, along with a number of other decorations and honours.

Prelude

Rorke’s Drift, known as kwaJimu (“Jim’s Land”) in the Zulu language, was a mission station and the former trading post of James Rorke, an Irish merchant. It was located near a drift, or ford, on the Buffalo (Mzinyathi) River, which at the time formed the border between the British colony of Natal and the Zulu Kingdom. On 9 January 1879, the British No. 3 (Centre) Column, under Lord Chelmsford, arrived and encamped at the drift.

On 11 January, the day after the British ultimatum to the Zulus expired, the column crossed the river and encamped on the Zulu bank. A small force consisting of B Company, 2nd Battalion, 24th (2nd Warwickshire) Regiment of Foot (2nd/24th) under Lieutenant Gonville Bromhead was detailed to garrison the post, which had been turned into a supply depot and hospital under the overall command of Brevet Major Henry Spalding, 104th Foot, a member of Chelmsford’s staff.

On 20 January, after reconnaissance patrolling and building of a track for its wagons, Chelmsford’s column marched to Isandlwana, approximately 6 miles (9.7 km) to the east, leaving behind the small garrison. A large company of the 2nd/3rd Natal Native Contingent (NNC) under Captain William Stevenson was ordered to remain at the post to strengthen the garrison.

This company numbered between 100 and 350 men.

Captain Thomas Rainforth’s G Company of the 1st/24th Foot was ordered to move up from its station at Helpmekaar, 10 miles (16 km) to the southeast, after its own relief arrived, to further fortify the drift. Later that evening a portion of the No. 2 Column under Brevet Colonel Anthony Durnford, late of the Royal Engineers, arrived at the drift and camped on the Zulu bank, where it remained through the next day.

Late on the evening of 21 January, Durnford was ordered to Isandlwana, as was a small detachment of No. 5 Field Company, Royal Engineers, commanded by Lieutenant John Chard, which had arrived on the 19th to repair the pontoons which bridged the Buffalo. Chard rode ahead of his detachment to Isandlwana on the morning of 22 January to clarify his orders, but was sent back to Rorke’s Drift with only his wagon and its driver to construct defensive positions for the expected reinforcement company, passing Durnford’s column en route in the opposite direction.

Sometime around noon on the 22nd, Major Spalding left the station for Helpmekaar to ascertain the whereabouts of Rainforth’s G Company, which was now overdue. He left Chard in temporary command. Chard rode down to the drift itself where the engineers’ camp was located. Soon thereafter, two survivors from Isandlwana – Lieutenant Gert Adendorff of the 1st/3rd NNC and a trooper from the Natal Carbineers – arrived bearing the news of the defeat and that a part of the Zulu impi was approaching the station.

Upon hearing this news, Chard, Bromhead, and another of the station’s officers, Acting Assistant Commissary James Dalton (of the Commissariat and Transport Department), held a quick meeting to decide the best course of action – whether to attempt a retreat to Helpmekaar or to defend their current position. Dalton pointed out that a small column, travelling in open country and burdened with carts full of hospital patients, would be easily overtaken and defeated by a numerically superior Zulu force, and so it was soon agreed that the only acceptable course was to remain and fight.

Defensive preparations

Once the British officers decided to stay, Chard and Bromhead directed their men to make preparations to defend the station. With the garrison’s some 400 men[15] working quickly, a defensive perimeter was constructed out of mealie bags. This perimeter incorporated the storehouse, the hospital, and a stout stone kraal. The buildings were fortified, with loopholes (firing holes) knocked through the external walls and the external doors barricaded with furniture.

At about 3:30 pm, a mixed troop of about 100 Natal Native Horse (NNH) under Lieutenant Alfred Henderson arrived at the station after having retreated in good order from Isandlwana. They volunteered to picket the far side of the Oscarberg (Shiyane), the large hill that overlooked the station and from behind which the Zulus were expected to approach.

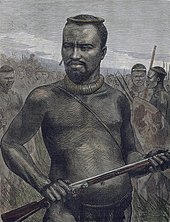

Prince Dabulamanzi kaMpande

With the defences nearing completion and battle approaching, Chard had several hundred men available to him: Bromhead’s B Company, Stevenson’s large NNC company, Henderson’s NNH troop, and various others (most of them hospital patients, but ‘walking wounded’) drawn from various British and colonial units. Adendorff also stayed, while the trooper who had ridden in with him galloped on to warn the garrison at Helpmekaar.

The force was sufficient, in Chard’s estimation, to fend off the Zulus. Chard posted the British soldiers around the perimeter, adding some of the more able patients, the ‘casuals’ and civilians, and those of the NNC who possessed firearms along the barricade. The rest of the NNC, armed only with spears, were posted outside the mealie bag and biscuit box barricade within the stone-walled cattle kraal.

The approaching Zulu force was vastly larger; the uDloko, uThulwana, inDlondo amabutho (regiments) of married men in their 30s and 40s and the inDlu-yengwe ibutho of young unmarried men mustered 3,000 to 4,000 warriors, none of them engaged during the battle at Isandlwana.

This Zulu force was the ‘loins’ or reserve of the army at Isandlwana and is often referred to as the Undi Corps. It was directed to swing wide of the British left flank and pass west and south of Isandlwana hill itself, in order to position itself across the line of communication and retreat of the British and their colonial allies in order to prevent their escape back into Natal by way of the Buffalo River ford leading to Rorke’s Drift.

By the time the Undi Corps reached Rorke’s Drift at 4:30 pm, they had fast-marched some 20 miles (32 km) from the morning encampment they had left at around 8 am, and they would spend almost the next eleven and a half hours continuously storming the British fortifications at Rorke’s Drift.

Most Zulu warriors were armed with an assegai (short spear) and a shield made of cowhide. The Zulu army drilled in the personal and tactical use and coordination of this weapons system. Some Zulus also had old muskets and antiquated rifles, though their marksmanship training was poor, and the quality and supply of powder and shot was dreadful.

The Zulu attitude towards firearms was that:

“The generality of Zulu warriors, however, would not have firearms – the arms of a coward, as they said, for they enable the poltroon to kill the brave without awaiting his attack.”

Even though their fire was not accurate, it was responsible for five of the seventeen British deaths at Rorke’s Drift.

While the Undi Corps had been led by inkhosi kaMapitha at the Isandlwana battle, the command of the Undi Corps passed to Prince Dabulamanzi kaMpande (half-brother of Cetshwayo kaMpande, the Zulu king) when kaMapitha was wounded during the pursuit of British fugitives from Isandlwana. Prince Dabulamanzi was considered rash and aggressive, and this characterisation was borne out by his violation of King Cetshwayo’s order to act only in defence of Zululand against the invading British soldiers and not carry the war over the border into enemy territory.

The Rorke’s Drift attack was an unplanned raid rather than any organised counter-invasion, with many of the Undi Corps Zulus breaking off to raid other African kraals and homesteads while the main body advanced on Rorke’s Drift.

At about 4:00 pm, Surgeon James Reynolds, Otto Witt – the Swedish missionary who ran the mission at Rorke’s Drift – and army chaplain Reverend George Smith came down from the Oscarberg hillside with the news that a body of Zulus was fording the river to the southeast and was “no more than five minutes away”. At this point, Witt decided to depart the station, as his family lived in an isolated farmhouse about 30 kilometres (19 mi) away, and he wanted to be with them. Witt’s native servant, Umkwelnantaba, left with him; so too did one of the hospital patients, Lieutenant Thomas Purvis of the 1st/3rd NNC.

——————————————————

Interview with Frank Bourne – Hero of Rorkes Drift

——————————————————

Battle

At about 4:20 pm, the battle began with Lieutenant Henderson’s NNH troopers, stationed behind the Oscarberg, briefly engaging the vanguard of the main Zulu force. However, tired from the battle and retreat from Isandlwana and short of carbine ammunition, Henderson’s men departed for Helpmekaar. Henderson himself reported to Lieutenant Chard that the enemy were close and that

“his men would not obey his orders but were going off to Helpmekaar”.

Henderson then followed his departing men. Upon witnessing the withdrawal of Henderson’s NNH troop, Captain Stevenson’s NNC company abandoned the cattle kraal and fled, greatly reducing the strength of the defending garrison. Outraged that Stevenson and some of his colonial NCOs also fled from the barricades, a few British soldiers fired after them, killing Corporal William Anderson.

With the Zulus nearly at the station, the garrison now numbered between 154 and 156 men.[30] Of these, only Bromhead’s company could be considered a cohesive unit. Additionally, up to 39 of his company were at the station as hospital patients, although only a handful of these were unable to take up arms.

With fewer men, Chard realised the need to modify the defences, and he gave orders for the construction of a biscuit-box wall through the middle of the post in order to make possible the abandonment of the hospital side of the station if the need arose.

At 4:30 pm, the Zulus rounded the Oscarberg and approached the south wall. Private Frederick Hitch, posted as lookout atop the storehouse, reported a large column of Zulus approaching. The Zulu vanguard, 600 men of the iNdluyengwe, attacked the south wall, which joined the hospital and the storehouse. The British opened fire at 500 yards (460 m).

The majority of the attacking Zulu force swept around to attack the north wall, while a few took cover and were either pinned by continuing British fire or retreated to the terraces of Oscarberg. There they began a harassing fire of their own. As this occurred, another Zulu force swept onto the hospital and north west wall.

Those British on the barricades — including Dalton and Bromhead — were soon engaged in fierce hand-to-hand fighting. The British wall was too high for the Zulus to scale, so they resorted to crouching under the wall, trying to get hold of the defenders’ Martini-Henry rifles, slashing at British soldiers with assegais or firing their weapons through the wall. At places, they clambered over each other’s bodies to drive the British off the walls but were driven back.

Zulu fire, both from those under the wall and around the Oscarberg, inflicted a few casualties, and five of the 17 defenders who were killed or mortally wounded in the action were struck while at the north wall.

—————————————-

Secrets Of The Dead – The Mystery Of Zulu Dawn

—————————————-

Defence of the hospital

Chard realised that the north wall, under almost constant Zulu attack, could not be held and, at 6:00 pm, he pulled his men back into the yard, abandoning the front two rooms of the hospital in the process. The hospital was becoming untenable; the loopholes had become a liability, as rifles poking out were grabbed at by the Zulus but, if the holes were left empty, the Zulu warriors stuck their own weapons through to fire into the rooms. Among the soldiers assigned to the hospital were Corporal William Wilson Allen and Privates Cole, Dunbar, Hitch, Horrigan, John Williams, Joseph Williams, Alfred Henry Hook, Robert Jones, and William Jones.

Privates Horrigan, John Williams, Joseph Williams and patients tried to hold the hospital entrance with rifles and fixed bayonets. Joseph Williams defended a small window, and 14 dead Zulus were found later beneath the window. As it became clear that the front of the building was being taken by the Zulus, John Williams began to hack a way of escape through the wall dividing the central room and a corner room in the back of the hospital. As he made a passable hole, the door into the central room came under furious attack from the Zulus, and he only had time to drag two bedridden patients out before the door gave way.

The corner room that John Williams had pulled the two patients into was occupied by Private Hook and another nine patients. John Williams hacked at the wall to the next room with his pick-axe, as Hook held off the Zulus. A firefight erupted as the Zulus fired through the door and Hook returned fire – but not without an assegai striking his helmet and stunning him.

Williams made the hole big enough to get into the next room, which was occupied only by patient Private Waters, and dragged the patients through. The last man out was Hook, who killed some Zulus who had knocked down the door before he dived through the hole. John Williams once again went to work, spurred by the fact that the roof was now on fire, as Hook defended the hole and Waters continued to fire through a loophole.

After fifty minutes, the hole was large enough to drag the patients through, and the men – save Privates Waters and Beckett, who hid in the wardrobe (Waters was wounded and Beckett died of assegai wounds) – were now in the last room, being defended by Privates Robert Jones and William Jones. From here, the patients clambered out through a window and then ran across the yard to the barricade.

Of the eleven patients, nine survived the trip, as did all the able-bodied men. According to James Henry Reynolds, only four defenders were killed in the hospital: one was a member of the Natal Native Contingent with a broken leg; Sgt Maxfield and Private Jenkins, who were ill with fever and refused to be moved. Reportedly, Jenkins was killed after being seized and stabbed, together with Private Adams who also refused to move. Private Cole, assigned to the hospital, was killed when he ran outside. Another hospital patient killed was Trooper Hunter of the Natal Mounted Police.

Among the hospital patients who escaped were a Corporal Mayer of the NNC; Bombardier Lewis of the Royal Artillery, and Trooper Green of the Natal Mounted Police, who was wounded in the thigh by a spent bullet. Private Conley with a broken leg was pulled to safety by Hook, although Conley’s leg was broken again in the process.

The cattle kraal and the bastion

The evacuation of the burning hospital completed the shortening of the perimeter. As night fell, the Zulu attacks grew stronger. The cattle kraal came under renewed assault and was evacuated by 10:00 pm, leaving the remaining men in a small bastion around the storehouse. Throughout the night, the Zulus kept up a constant assault against the British positions; Zulu attacks only began to slacken after midnight, and they finally ended by 2:00 am, being replaced by a constant harassing fire from Zulu firearms until 4:00 am.

By that time, the garrison had lost 14 dead. Two others were mortally wounded and 8 more – including Dalton – were seriously wounded. Virtually every man had some kind of wound. They were all exhausted, having fought for the better part of ten hours and were running low on ammunition. Of 20,000 rounds in reserve at the mission, only 900 remained.

——————————————————

Those that died in the Zulu war 1879

——————————————————

Aftermath

As dawn broke, the British could see that the Zulus were gone; all that remained were the dead and severely wounded. Patrols were dispatched to scout the battlefield, recover rifles, and look for survivors, many of whom were executed when found. At roughly 7:00 am, an Impi of Zulus suddenly appeared, and the British manned their positions again.

No attack materialised however, as the Zulus had been on the move for six days prior to the battle and had not eaten properly for two. In their ranks were hundreds of wounded, and they were several days’ march from any supplies. Soon after their appearance, the Zulus left the way they had come.

Around 8:00 am, another force appeared, and the redcoats left their breakfast to man their positions again. However, the force turned out to be the vanguard of Lord Chelmsford‘s relief column.

Breakdown of British and colonial casualties:

- 1st/24th Foot: 4 killed or mortally wounded in action; 2 wounded

- 2nd/24th Foot: 9 killed or mortally wounded in action; 9 wounded

- Commissariat and Transport Department: 1 killed in action; 1 wounded

- Natal Mounted Police: 1 killed in action; 1 wounded

- 1st/3rd NNC: 1 killed in action

- 2nd/3rd NNC: 2 wounded

Also, as mentioned, one member of Stevenson’s 2nd/3rd NNC, Corporal William Anderson, was killed by British fire while fleeing the station just prior to the arrival of the Zulus.

351 Zulu bodies were counted after the battle, but it has been estimated that at least 500 wounded and captured Zulus might have been massacred as well.

Having witnessed the carnage at Isandlwana, the members of Chelmsford’s relief force had no mercy for the captured, wounded Zulus they came across. Nor did the station’s defenders. Trooper William James Clarke of the Natal Mounted Police described in his diary that:

“altogether we buried 375 Zulus and some wounded were thrown into the grave. Seeing the manner in which our wounded had been mutilated after being dragged from the hospital … we were very bitter and did not spare wounded Zulus”

Laband, in his book The Zulu Response to the British Invasion of 1879, accepts the estimate of 600 that Shepstone had from the Zulus.

Samuel Pitt, who served as a private in B Company during the battle, told The Western Mail in 1914 that the official enemy death toll was too low:

“We reckon we had accounted for 875, but the books will tell you 400 or 500”.

Lieutenant Horace Smith-Dorrien, a member of Chelmsford’s staff, wrote that the day after the battle an improvised gallows was used “for hanging Zulus who were supposed to have behaved treacherously”.[43]

Victoria Crosses and Distinguished Conduct Medals

Eleven Victoria Crosses were awarded to the defenders of Rorke’s Drift, seven of them to soldiers of the 2nd/24th Foot – the most ever received in a single action by one regiment (although not, as commonly thought, the most awarded in a single action or the most in a day: 16 were awarded at the Battle of Inkerman, on 5 November 1854; 28 were awarded during the Second Relief of Lucknow, 14–22 November 1857).

Four Distinguished Conduct Medals were also awarded. This high number of awards for bravery has been interpreted as a reaction to the earlier defeat at the Battle of Isandlwana – the extolling of the victory at Rorke’s Drift drawing the public’s attention away from the great defeat at Isandlwana and the fact that Lord Chelmsford and Bartle Frere had instigated the war without the approval of Her Majesty’s Government.

Certainly, Sir Garnet Wolseley, taking over as commander-in-chief from Lord Chelmsford later that year, was unimpressed with the awards made to the defenders of Rorke’s Drift, saying “it is monstrous making heroes of those who, shut up in buildings at Rorke’s Drift, could not bolt and fought like rats for their lives, which they could not otherwise save”.

Several historians have challenged this assertion and pointed out that the victory stands on its own merits, regardless of other concerns. Victor Davis Hanson responded to it directly in “Why the West has Won” saying

, “Modern critics suggest such lavishness in commendation was designed to assuage the disaster at Isandhlwana and to reassure a skeptical Victorian public that the fighting ability of the British soldier remained unquestioned. Maybe, maybe not, but in the long annals of military history, it is difficult to find anything quite like Rorke’s Drift, where a beleaguered force, outnumbered forty to one, survived and killed twenty men for every defender lost”.

Awarded the Victoria Cross:

- Lieutenant John Rouse Merriott Chard, 5th Field Coy, Royal Engineers

- Lieutenant Gonville Bromhead; B Coy, 2nd/24th Foot

- Corporal William Wilson Allen; B Coy, 2nd/24th Foot

- Private Frederick Hitch; B Coy, 2nd/24th Foot

- Private Alfred Henry Hook; B Coy, 2nd/24th Foot

- Private Robert Jones; B Coy, 2nd/24th Foot

- Private William Jones; B Coy, 2nd/24th Foot

- Private John Williams; B Coy, 2nd/24th Foot

- Surgeon James Henry Reynolds; Army Medical Department

- Acting Assistant Commissary James Langley Dalton; Commissariat and Transport Department

- Corporal Christian Ferdinand Schiess; 2nd/3rd Natal Native Contingent

In 1879 there was no provision for the posthumous granting of the Victoria Cross, and so it could not be awarded to anyone who had died in performing an act of bravery. In light of this, an unofficial ‘twelfth VC’ may be added to those listed: Private Joseph Williams, B Coy, 2nd/24th Foot, who was killed during the fight in the hospital and for whom it was mentioned in despatches that “had he lived he would have been recommended for the Victoria Cross”.

Awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal:

- Gunner John Cantwell; N Batt, 5th Brig Royal Horse Artillery (demoted from bombardier wheeler the day before the battle)

- Private John William Roy; 1st/24th Foot

- Colour Sergeant Frank Edward Bourne; B Coy, 2nd/24th Foot

- Second Corporal Francis Attwood; Army Service Corps

On 15 January 1880, a submission for a DCM was also made for Private Michael McMahon (Army Hospital Corps). The submission was cancelled on 29 January 1880 for absence without leave and theft.

Depictions and dramatisations

The events surrounding the assault on Rorke’s Drift were first dramatised by military painters, notably Elizabeth Butler and Alphonse de Neuville. Their work was vastly popular in their day among the citizens of the British empire.

In 1914, a touring English Northern Union rugby league team defeated Australia 14-6 to win the Ashes in the final Test match. Depleted by injuries and fielding only ten men for much of the second half, the English outclassed and outfought the Australians in what quickly became known as the ‘Rorke’s Drift Test‘.

The 1964 film Zulu is a depiction of the Battle of Rorke’s Drift. The film received generally positive reviews from the critics. Some details of the film’s account have, however, been criticised[by whom?] as historically inaccurate (for example, in the movie the regiment is called the South Wales Borderers but the unit was not in fact called that until two years after the battle, although the regiment had been based at Brecon in South Wales since 1873).[54] While most of the men of the 1st Battalion, 24th Regiment of Foot (1/24) were recruited from the industrial towns and agricultural classes of England, principally from Birmingham and adjacent southwest counties, only 10 soldiers of the 1/24 that fought in the battle were Welsh. Many of the soldiers of the junior battalion, the 2/24, were Welshmen.

Of the 122 soldiers of the 24th Regiment present at the Battle of Rorke’s Drift, 49 are known to have been of English nationality, 32 were Welsh, 16 were Irish, 1 was a Scot, and 3 were born overseas. The nationalities of the remaining 21 are unknown.

In 1990 the game developer Impressions Games released a video game based on the historical battle. The battle was also featured by Mad Doc Software in its 2006 strategy game Empire Earth II: The Art of Supremacy as one of its “turning point” battle modes.

The battle of Rorke’s Drift was given a chapter in military historian Victor Davis Hanson‘s book Carnage and Culture (2002) as one of several landmark battles demonstrating the superior effectiveness of Western military practices

——————————————

Forgotten soldiers who fought 4,000 Zulus during battle of Rorke’s Drift

They were the Brummies and Black Country fighting men who thwarted 4,000 Zulus in a battle that will forever be remembered among one of the most heroic stands in British military history.

They were the Brummies and Black Country fighting men who thwarted 4,000 Zulus in a battle that will forever be remembered among one of the most heroic stands in British military history.

Rorke’s Drift – the subject of a blockbuster movie – will never be forgotten. Eleven Victoria Crosses were handed out following the bloody encounter – the most spawned by one battle.

But, with the exception of the 11 who received this country’s highest forces’ honour, the local lads who braved knobkerries clubs, rifles and assegai spears have faded from the history books.

Now, on Remembrance Sunday – a day when we pay tribute to those prepared to make the ultimate sacrifice for this country – we salute the few from the 24th (Warwickshire) Regiment, although the unit, spawned in Warley, had based itself in Brecon by the time of the Zulu conflict.

Of the 122 of the regiment’s representatives at Rorke’s Drift, 49 were English, 32 Welsh, 16 Irish and there was a lone Scot.

Only four are believed to have been born and bred in Warwickshire. Their average age was 23, their average weight 10stone and their average height 5ft 3ins.

They were among the 139 defenders – a mix of British infantry and Natal irregulars – who defied the massive odds against them at the tiny garrison of Rorke’s Drift. Seeking sanctuary behind barricades of biscuit boxes and mealie bags, they held firm against a ceaseless onslaught that began at 4.20pm on January 22, 1879, and raged until dawn.

It has become the ultimate underdog victory. That red ribbon of men killed 351 Zulus and wounded 500 more: the African warriors decision to set alight the garrison hospital making them easy targets during night attacks. We lost 17.

Among them was Sergeant Joseph Lenford Windridge, played by Joe Powell in the 1964 film. He lived in Aston and after leaving the army found employment as a lamp-maker’s clerk, but his was a Civvy Street existence dogged by tragedy. Six of his 11 children died from TB.

Windridge died from a stroke in 1902, aged 60, and was laid to rest in an unmarked, communal grave at Witton Cemetery. This year a campaign was launched to place a memorial on the plot.

Two other Birmingham survivors of the battle, Privates Robert Cole and Samuel Parry, are also buried at Witton and, again, their graves are unmarked.

Birmingham-born William Tasker was probably more deserving of a VC than many who received them.

The 33-year-old fought on despite blooding pouring from his head, the thin flesh split open by splinters from a musket ball. He died in his home city aged 42.

An unmarked grave was also the undignified final resting place for Joseph Bromwich, who fought at the battle alongside elder brother Charles. Joseph, buried at Bilston Cemetery, was 22 when he faced the Zulus. He was a broken man when he left the services and he died on February 25, 1916, with tongue cancer.

What’s clear from reading the documents that exist – many of them contradictory – is that troops emerged from Rorke’s Drift mentally scarred and never recovered from the harrowing experience.

William Jones, a down-and-out, was found wandering the streets of Manchester after selling his VC for £6. His family took him in, but terrified Jones remained convinced Zulus were coming through the windows of the modest home. He was declared insane and died in a mental institution.

Robert Jones VC took his own life with a shotgun.

——————————————————————————-

Last remnant of Rorke’s Drift:

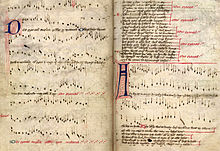

Tiny scrap of paper gives rare first-hand account of the day British redcoats fought off Zulus, Captain, thousands of them

A rare first-hand account of the Battle of Rorke’s Drift – where 150 soldiers successfully fought off 4,000 Zulu warriors, has gone on display for the first time.

Written by one of the British heroes on a tiny scrap of paper, it is thought to be the earliest account of the battle which was immortalised in the 1964 film Zulu, starring Michael Caine and Stanley Baker.

Assistant Commissary Officer (ACO) Walter Dunne’s letter to his friend Captain W.J. Warneford at Cape Colony, describes how he and a vastly outnumbered group of soldiers successfully defended their missionary outpost at Rorke’s Drift in South Africa.

ASSISTANT COMISSARY OFFICER WALTER DUNNE’S LETTER IN FULL

Rorke’s Drift/ 24 Jan.r ’79/

My dear Warneford,

Sad news about the 1/24th. (1st Battalion, 24th Foot) 5Cd commanded by Col. Pulleine were cut to pieces and the camp sacked. 20 Officers are missing.

About 1000 of the Kafirs came in here and attacked us on the same day (22nd). We had got about 2 hours notice and fortified the place with trap of grain biscuit boxes &c. They came on most determinedly on all sides. They drove our fellows out of the Hospital, killed the patients and burned the place.

They made several attempts to storm us but the soldiers (B Co of 24th under Bromhead) kept up such a steady killing fire that they were driven back each time. We had only 80 men, the contingent having bolted before a shot was fired. The fight was kept up all night & in the morning the Kafirs retreated leaving 351 dead bodies.

Dalton was wounded in the shoulder and temp clerk Byrne killed & 12 of the men… W A Dunne (over)

Some of the missing are Pulleine, Col. Dunford, Capt. Russell, Hodson (killed), Anstey, Daly, Mostyn, Dyer, Griffith, Pope, Austin, Pulleine (2 Mr.) Shepherd (S… major) Wardell (killed), Younghusband, Degacher, Porteous, Carage Dyson, Atkinson – Coghill is believed to have escaped & also Melvill.

—————————

Zulu Dawn (1979) – Final Battle

—————————